Xerxes I, commonly known as Xerxes the Great, was the fourth King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, ruling from 486 to 465 BC. He was the son and successor of Darius the Great, and his mother was Atossa, a daughter of Cyrus the Great, the founder of the Achaemenid empire. Like his father, he ruled the empire at its territorial peak, ruling from 486 BC until his assassination in 465 BC at the hands of Artabanus, the commander of the royal bodyguard.

Lycia was a state or nationality that flourished in Anatolia from 15–14th centuries BC to 546 BC. It bordered the Mediterranean Sea in what is today the provinces of Antalya and Muğla in Turkey as well some inland parts of Burdur Province. The state was known to history from the Late Bronze Age records of ancient Egypt and the Hittite Empire. Lycia was populated by speakers of the Luwian language group. Written records began to be inscribed in stone in the Lycian language after Lycia's involuntary incorporation into the Achaemenid Empire in the Iron Age. At that time (546 BC) the Luwian speakers were displaced as Lycia received an influx of Persian speakers. Ancient sources seem to indicate that an older name of the region was Alope.

Mausolus was a ruler of Caria and a satrap of the Achaemenid Empire. He enjoyed the status of king or dynast by virtue of the powerful position created by his father Hecatomnus, who was the first satrap of Caria from the hereditary Hecatomnid dynasty. Alongside Caria, Mausolus also ruled Lycia and parts of Ionia and the Dodecanese islands. He is best known for his monumental tomb and one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, the construction of which has traditionally been ascribed to his wife and sister Artemisia.

Immortals or Persian Immortals was the name given by Herodotus to an elite heavy infantry unit of 10,000 soldiers in the army of the Achaemenid Empire. The unit served in a dual capacity through its role as imperial guard alongside its contribution to the ranks of the Persian Empire's standing army. While it primarily consisted of Persians, the Immortals force also included Medes and Elamites. Essential questions regarding the historic unit remain unanswered because authoritative sources are missing.

A peltast was a type of light infantryman, originating in Thrace and Paeonia, and named after the kind of shield he carried. Thucydides mentions the Thracian peltasts, while Xenophon in the Anabasis distinguishes the Thracian and Greek peltast troops. The peltast often served as a skirmisher in Hellenic and Hellenistic armies. In the Medieval period, the same term was used for a type of Byzantine infantryman.

The acinaces, also spelled akinakes or akinaka is a type of dagger or xiphos used mainly in the first millennium BCE in the eastern Mediterranean Basin, especially by the Medes, Scythians, Persians and Caspians, then by the Greeks.

In the writings of the Ancient Greek chronicler Herodotus, the phrase earth and water is used to represent the demand by the Persian Empire of formal tribute from the cities or people who surrendered to them.

Autophradates was a Persian Satrap of Lydia, who also distinguished himself as a general in the reign of Artaxerxes III and Darius III.

Lycians is the name of various peoples who lived, at different times, in Lycia, a geopolitical area in Anatolia.

The Achaemenid Empire issued coins from 520 BC–450 BC to 330 BC. The Persian daric was the first gold coin which, along with a similar silver coin, the siglos represented the first bimetallic monetary standard. It seems that before the Persians issued their own coinage, a continuation of Lydian coinage under Persian rule is likely. Achaemenid coinage includes the official imperial issues, as well as coins issued by the Achaemenid provincial governors (satraps), such as those stationed in Asia Minor.

The Satrapy of Lydia, known as Sparda in Old Persian, was an administrative province (satrapy) of the Achaemenid Empire, located in the ancient kingdom of Lydia, with Sardis as its capital.

Arabia was a satrapy (province) of the Achaemenid Empire. Achaemenid Arabia corresponded to the lands between Nile Delta (Egypt) and Mesopotamia, later known to Romans as Arabia Petraea. According to Herodotus, Cambyses did not subdue the Arabs when he attacked Egypt in 525 BCE. His successor Darius the Great mentions the Arabs in the Behistun inscription from the first years of his reign, and in later texts. This suggests that Darius might have conquered this part of Arabia, or that it was originally part of another province, perhaps Achaemenid Babylonia, but later became its own province.

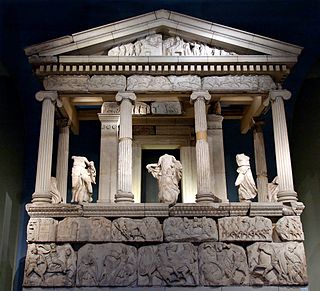

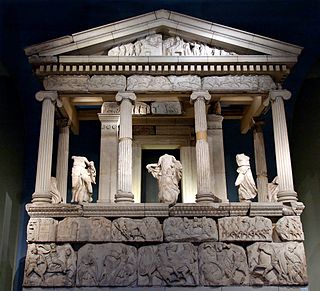

The Nereid Monument is a sculptured tomb from Xanthos in Lycia, close to present-day Fethiye in Mugla Province, Turkey. It took the form of a Greek temple on top of a base decorated with sculpted friezes, and is thought to have been built in the early fourth century BC as a tomb for Arbinas, the Xanthian dynast who ruled western Lycia under the Achaemenid Empire.

The Tomb of Payava is a Lycian tall rectangular free-standing barrel-vaulted stone sarcophagus, and one of the most famous tombs of Xanthos. It was built in the Achaemenid Persian Empire, for Payava, who was probably the ruler of Xanthos, Lycia at the time, in around 360 BC. The tomb was discovered in 1838 and brought to England in 1844 by the explorer Sir Charles Fellows. He described it as a 'Gothic-formed Horse Tomb'. According to Melanie Michailidis, though bearing a "Greek appearance", the Tomb of Payava, the Harpy Tomb and the Nereid Monument were built according to the main Zoroastrian criteria "by being composed of thick stone, raised on plinths off the ground, and having single windowless chambers".

The Harpy Tomb is a marble chamber from a pillar tomb that stands in the abandoned city of Xanthos, capital of ancient Lycia, a region of southwestern Anatolia in what is now Turkey. Built in the Persian Achaemenid Empire, and dating to approximately 480–470 BC, the chamber topped a tall pillar and was decorated with marble panels carved in bas-relief. The tomb was built for an Iranian prince or governor of Xanthus, perhaps Kybernis.

The Xanthian Obelisk, also known as the Xanthos or Xanthus Stele, the Xanthos or Xanthus Bilingual, the Inscribed Pillar of Xanthos or Xanthus, the Harpagus Stele, the Pillar of Kherei and the Columna Xanthiaca, is a stele bearing an inscription currently believed to be trilingual, found on the acropolis of the ancient Lycian city of Xanthos, or Xanthus, near the modern town of Kınık in southern Turkey. It was created when Lycia was part of the Persian Achaemenid Empire, and dates in all likelihood to ca. 400 BC. The pillar is seemingly a funerary marker of a dynastic satrap of Achaemenid Lycia. The dynast in question is mentioned on the stele, but his name had been mostly defaced in the several places where he is mentioned: he could be Kherei (Xerei) or more probably his predecessor Kheriga.

The Achaemenid conquest of the Indus Valley occurred from the 6th to 4th centuries BCE, and saw the Persian Achaemenid Empire take control of regions in the northwestern Indian subcontinent that predominantly comprise the territory of modern-day Pakistan. The first of two main invasions was conducted around 535 BCE by the empire's founder, Cyrus the Great, who annexed the regions west of the Indus River that formed the eastern border of the Achaemenid Empire. Following Cyrus' death, Darius the Great established his dynasty and began to re-conquer former provinces and further expand the empire. Around 518 BCE, Persian armies under Darius crossed the Himalayas into India to initiate a second period of conquest by annexing regions up to the Jhelum River in Punjab.

Hydarnes II, also known as Hydarnes the Younger was a Persian commander of the Achaemenid Empire in the 5th century BC. He was the son of Hydarnes, satrap of the Persian empire and one of the seven conspirators against Gaumata.

Xanthos, also called Xanthus, was a chief city state of the Lycians, an indigenous people of southwestern Anatolia. Many of the tombs at Xanthos are pillar tombs, formed of a stone burial chamber on top of a large stone pillar. The body would be placed in the top of the stone structure, elevating it above the landscape. The tombs are for men who ruled in a Lycian dynasty from the mid-6th century to the mid-4th century BCE and help to show the continuity of their power in the region. Not only do the tombs serve as a form of monumentalization to preserve the memory of the rulers, but they also reveal the adoption of Greek style of decoration.

Arbinas, also Erbinas, Erbbina, was a Lycian Dynast who ruled circa 430/20-400 BCE. He is most famous for his tomb, the Nereid Monument, now on display in the British Museum. Coinage seems to indicate that he ruled in the western part of Lycia, around Telmessos, while his tomb was established in Xanthos. He was a subject of the Achaemenid Empire.