Berengar of Tours, in Latin Berengarius Turonensis, was an 11th-century French Christian theologian and archdeacon of Angers, a scholar whose leadership of the cathedral school at Chartres set an example of intellectual inquiry through the revived tools of dialectic that was soon followed at cathedral schools of Laon and Paris. Berengar of Tours was distinguished from mainline Catholic theology by two views: his assertion of the supremacy of Scripture and his denial of transubstantiation.

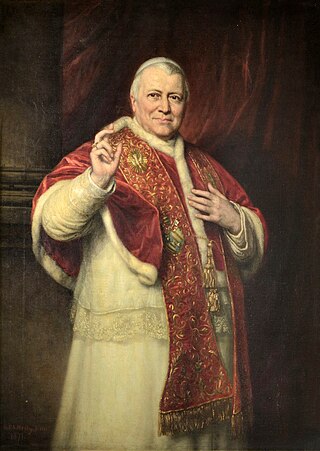

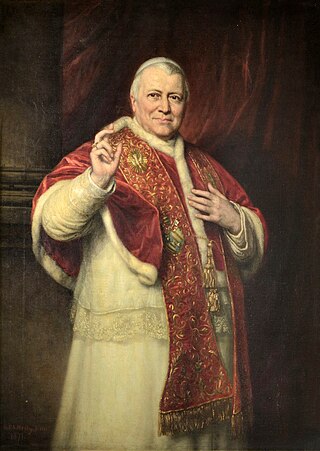

Pope Pius IX was head of the Catholic Church from 1846 to 1878. His reign of 32 years is the second longest of any pope in history, behind that of Saint Peter. He was notable for convoking the First Vatican Council in 1868 and for permanently losing control of the Papal States in 1870 to the Kingdom of Italy. Thereafter, he refused to leave Vatican City, declaring himself a "prisoner in the Vatican".

Pope Pius VII was head of the Catholic Church from 14 March 1800 to his death in August 1823. He ruled the Papal States from June 1800 to 17 May 1809 and again from 1814 to his death. Chiaramonti was also a monk of the Order of Saint Benedict in addition to being a well-known theologian and bishop.

Pope Pius XI, born Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti, was the Bishop of Rome and supreme pontiff of the Catholic Church from 6 February 1922 to 10 February 1939. He also became the first sovereign of the Vatican City State upon its creation as an independent state on 11 February 1929. He remained head of the Catholic Church until his death in February 1939. His papal motto was "Pax Christi in Regno Christi", translated as "The Peace of Christ in the Reign of Christ".

Traditionalist Catholicism is a movement that emphasizes beliefs, practices, customs, traditions, liturgical forms, devotions and presentations of teaching associated with the Catholic Church before the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965). Traditionalist Catholics particularly emphasize the Tridentine Mass, the Roman Rite liturgy largely replaced in general use by the post-Second Vatican Council Mass of Paul VI.

The Holy Prepuce, or Holy Foreskin, is one of several relics attributed to Jesus, consisting of the foreskin removed during the circumcision of Jesus. At various points in history, a number of churches in Europe have claimed to possess the Prepuce, sometimes at the same time. Various miraculous powers have been ascribed to it.

Alfred Firmin Loisy was a French Roman Catholic priest, professor and theologian generally credited as a founder of modernism in the Roman Catholic Church. He was a critic of traditional views of the interpretation of the Bible, and argued that biblical criticism could be helpful for a theological interpretation of the Bible.

Christ the King is a title of Jesus in Christianity referring to the idea of the Kingdom of God where Christ is described as being seated at the right hand of God.

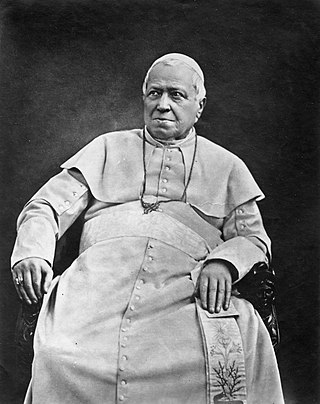

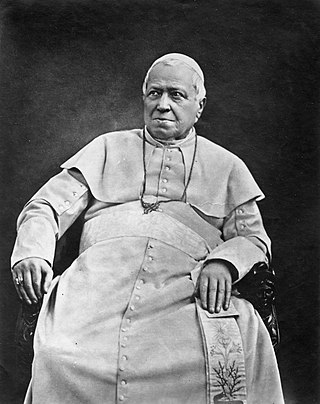

James Cardinal Gibbons was a senior-ranking American prelate of the Catholic Church who served as apostolic vicar of the Apostolic Vicariate of North Carolina from 1868 to 1872, bishop of the Diocese of Richmond in Virginia from 1872 to 1877, and as ninth archbishop of the Archdiocese of Baltimore in Maryland from 1877 until his death.

The papal conclave held from 18 to 20 February 1878 saw the election of Vincenzo Pecci, who took the name Leo XIII as pope. Held after the death of Pius IX, who had had the longest pontificate since Saint Peter, it was the first election of a pope who would not rule the Papal States. It was the first to meet in the Apostolic Palace in the Vatican because the venue used earlier in the 19th century, the Quirinal Palace, was now the palace of the king of Italy, Umberto I.

The history of the Catholic Church is integral to the history of Christianity as a whole. It is also, according to church historian Mark A. Noll, the "world's oldest continuously functioning international institution." This article covers a period of just under two thousand years.

Louis Baunard was a French rector of the Catholic University of Lille and historian.

Jean Marcel Pierre Auguste Vérot, known commonly as Augustin Vérot was a French-born American prelate of the Catholic Church who served as the first bishop of the Diocese of St. Augustine in Florida (1870–1876).

According to the Catholic Church, a Church Council is ecumenical ("world-wide") if it is "a solemn congregation of the Catholic bishops of the world at the invitation of the Pope to decide on matters of the Church with him". The wider term "ecumenical council" relates to Church councils recognised by both Eastern and Western Christianity.

Papal infallibility is a dogma of the Catholic Church which states that, in virtue of the promise of Jesus to Peter, the Pope when he speaks ex cathedra is preserved from the possibility of error on doctrine "initially given to the apostolic Church and handed down in Scripture and tradition". It does not mean that the pope cannot sin or otherwise err in some capacity, though he is prevented by the assistance of the Holy Spirit from issuing heretical teaching even in his non-infallible Magisterium, as a corollary of indefectibility. This doctrine, defined dogmatically at the First Vatican Council of 1869–1870 in the document Pastor aeternus, is claimed to have existed in medieval theology and to have been the majority opinion at the time of the Counter-Reformation.

Catholic bishops in Nazi Germany differed in their responses to the rise of Nazi Germany, World War II, and the Holocaust during the years 1933–1945. In the 1930s, the Episcopate of the Catholic Church of Germany comprised 6 Archbishops and 19 bishops while German Catholics comprised around one third of the population of Germany served by 20,000 priests. In the lead up to the 1933 Nazi takeover, German Catholic leaders were outspoken in their criticism of Nazism. Following the Nazi takeover, the Catholic Church sought an accord with the Government, was pressured to conform, and faced persecution. The regime had flagrant disregard for the Reich concordat with the Holy See, and the episcopate had various disagreements with the Nazi government, but it never declared an official sanction of the various attempts to overthrow the Hitler regime. Ian Kershaw wrote that the churches "engaged in a bitter war of attrition with the regime, receiving the demonstrative backing of millions of churchgoers. Applause for Church leaders whenever they appeared in public, swollen attendances at events such as Corpus Christi Day processions, and packed church services were outward signs of the struggle of ... especially of the Catholic Church - against Nazi oppression". While the Church ultimately failed to protect its youth organisations and schools, it did have some successes in mobilizing public opinion to alter government policies.

Popes Pius XI (1922–1939) and Pius XII (1939–1958) led the Catholic Church during the rise and fall of Nazi Germany. Around a third of Germans were Catholic in the 1930s, most of them lived in Southern Germany; Protestants dominated the north. The Catholic Church in Germany opposed the Nazi Party, and in the 1933 elections, the proportion of Catholics who voted for the Nazi Party was lower than the national average. Nevertheless, the Catholic-aligned Centre Party voted for the Enabling Act of 1933, which gave Adolf Hitler additional domestic powers to suppress political opponents as Chancellor of Germany. President Paul Von Hindenburg continued to serve as Commander and Chief and he also continued to be responsible for the negotiation of international treaties until his death on 2 August 1934.

Louis-Marie Grignion de Montfort, TOSD was a French Catholic priest known for his preaching and his influence on Mariology. He was made a missionary apostolic by Pope Clement XI. Montfort wrote a number of books which went on to become classic Catholic titles and influenced several popes. His most notable works regarding Marian devotions are contained in Secret of the Rosary and True Devotion to Mary.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to the Catholic Church:

Catholic resistance to Nazi Germany was a component of German resistance to Nazism and of Resistance during World War II. The role of the Catholic Church during the Nazi years remains a matter of much contention. From the outset of Nazi rule in 1933, issues emerged which brought the church into conflict with the regime and persecution of the church led Pope Pius XI to denounce the policies of the Nazi Government in the 1937 papal encyclical Mit brennender Sorge. His successor Pius XII faced the war years and provided intelligence to the Allies. Catholics fought on both sides in World War II and neither the Catholic nor Protestant churches as institutions were prepared to openly oppose the Nazi State.