Mandaeans, also known as Mandaean Sabians or simply as Sabians, are an ethnoreligious group who are followers of Mandaeism. They believe that John the Baptist was the final and most important prophet. They may have been among the earliest religious groups to practice baptism, as well as among the earliest adherents of Gnosticism, a belief system of which they are the last surviving representatives today. The Mandaeans were originally native speakers of Mandaic, an Eastern Aramaic language, before they nearly all switched to Mesopotamian Arabic or Persian as their main language.

Mandaic, or more specifically Classical Mandaic, is the liturgical language of Mandaeism and a South Eastern Aramaic variety in use by the Mandaean community, traditionally based in southern parts of Iraq and southwest Iran, for their religious books. Mandaic, or Classical Mandaic is still used by Mandaean priests in liturgical rites. The modern descendant of Mandaic or Classical Mandaic, known as Neo-Mandaic or Modern Mandaic, is spoken by a small group of Mandaeans around Ahvaz and Khorramshahr in the southern Iranian Khuzestan province.

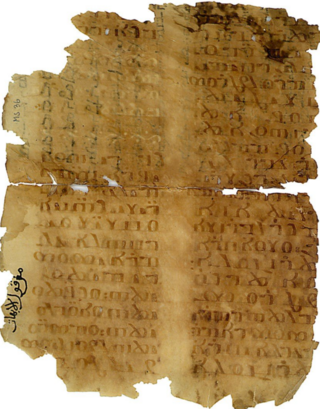

The Mandaic alphabet is a writing system primarily used to write the Mandaic language. It is thought to have evolved between the second and seventh century CE from either a cursive form of Aramaic or from Inscriptional Parthian. The exact roots of the script are difficult to determine. It was developed by members of the Mandaean faith of Lower Mesopotamia to write the Mandaic language for liturgical purposes. Classical Mandaic and its descendant Neo-Mandaic are still in limited use. The script has changed very little over centuries of use.

Mandaeism, sometimes also known as Nasoraeanism or Sabianism, is a Gnostic, monotheistic and ethnic religion with Greek, Iranian, and Jewish influences. Its adherents, the Mandaeans, revere Adam, Abel, Seth, Enos, Noah, Shem, Aram, and especially John the Baptist. Mandaeans consider Adam, Seth, Noah, Shem and John the Baptist prophets, with Adam being the founder of the religion and John being the greatest and final prophet.

Christian Palestinian Aramaic was a Western Aramaic dialect used by the Melkite Christian community, probably of Jewish descent, in Palestine, Transjordan and Sinai between the fifth and thirteenth centuries. It is preserved in inscriptions, manuscripts and amulets. All the medieval Western Aramaic dialects are defined by religious community. CPA is closely related to its counterparts, Jewish Palestinian Aramaic (JPA) and Samaritan Aramaic (SA). CPA shows a specific vocabulary that is often not paralleled in the adjacent Western Aramaic dialects.

Incantation bowls are a form of protective magic found in what is now Iraq and Iran. Produced in the Middle East during late antiquity from the sixth to eighth centuries, particularly in Upper Mesopotamia and Syria, the bowls were usually inscribed in a spiral, beginning from the rim and moving toward the center. Most are inscribed in Jewish Babylonian Aramaic.

Rudolf Macúch was a Slovak linguist, naturalized as German after 1974.

Mullissu is a goddess who is the consort of the Assyrian god Asshur. Mullissu may be identical with the Sumerian goddess Ninlil, wife of the god Enlil, which would parallel the fact that Asshur himself was modeled on Enlil. Mullissu's name was written dnin.líl. Mullissu is identified with Ishtar of Nineveh in the Neo-Assyrian Empire times.

The historiola is a modern term for a kind of incantation incorporating a short mythic story that provides the paradigm for the desired magical action. It can be found in ancient Mesopotamian, Egyptian and Greek mythology, in the Aramaic Uruk incantation, incorporated in Mandaean incantations, as well as in Jewish kabbalah. There are also Christian examples evoking Christian legends.

In Mandaeism, Kiwan, Kiuan, or Kewan is the Mandaic name for the planet Saturn. Kiwan is one of the seven planets, who are part of the entourage of Ruha in the World of Darkness.

The Aramaic Uruk incantation acquired 1913 by the Louvre, Paris and stored there under AO 6489 is a unique Aramaic text written in Late Babylonian cuneiform syllable signs and dates to the Seleucid Empire ca. 150 BCE. The finding site is the reš-sanctuary in the ancient city of Uruk (Warka), therefore the label “Uruk”. Particular about this incantation text is that it contains a magical historiola which is divided up into two nearly repetitive successive parts, a text genre that finds its continuation in the Aramaic magical text corpus of late antiquity from Iraq and Iran, most prominently in incantation bowls and Mandaic lead rolls.

Mandaean cosmology is the Gnostic conception of the universe in the religion of Mandaeism.

Matthew Morgenstern, also known as Moshe Morgenstern, is an Israeli linguist and religious studies scholar known for his work on Eastern Aramaic languages, especially Mandaic. He is currently Full Professor in the Department of Hebrew Language and Semitic Linguistics at Tel Aviv University.

Bogdan Burtea is a Romanian religious studies scholar and Semiticist currently based in Germany. His main interests are Mandaic, Aramaic, and Ethiopic studies.

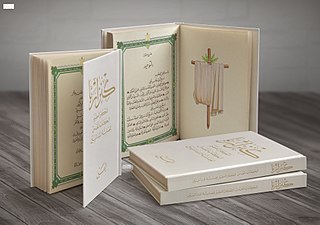

The Scroll of the Great Baptism is a Mandaean religious text. It is a ritual scroll describing the 360 baptisms (masbutas) for a polluted priest. The scroll is also called "Fifty Baptisms" and the Raza Rba ḏ-Zihrun.

In Mandaeism, Sin or Sen is the Mandaic name for the Moon. Sin is one of the seven planets, who are part of the entourage of Ruha in the World of Darkness.

In Mandaeism, Shamish or Šamiš is the Mandaic name for the Sun. Shamish is one of the seven classical planets, who are part of the entourage of Ruha in the World of Darkness.

In Mandaeism, Libat is the Mandaic name for the planet Venus. Libat is one of the seven planets, who are part of the entourage of Ruha in the World of Darkness.

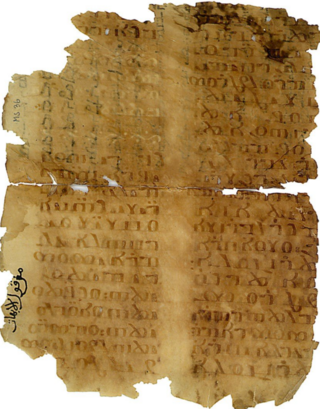

MS Drower 43 is a Mandaic manuscript that contains over a dozen qmaha texts used for exorcism and protection against evil. It is part of the Drower Collection in the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford.