The Qulasta, also spelled Qolastā in older sources, is a compilation of Mandaean prayers. The Mandaic word qolastā means "collection".

A rasta is a white ceremonial garment that Mandaeans wear during most baptismal rites, religious ceremonies, and during periods of uncleanliness. It signifies the purity of the World of Light. The rasta is worn equally by the laypersons and the priests. If a Mandaean dies in clothes other than a rasta, it is believed that they will not reenter the World of Light, unless the rite "Ahaba ḏ-Mania" can be performed "for those who have died not wearing the ritual garment."

An uthra or ʿutra is a "divine messenger of the light" in Mandaeism. Charles G. Häberl and James F. McGrath translate it as "excellency". Jorunn Jacobsen Buckley defines them as "Lightworld beings, called 'utras ." Aldihisi (2008) compares them to the yazata of Zoroastrianism. According to E. S. Drower, "an 'uthra is an ethereal being, a spirit of light and Life."

In Mandaeism, Hayyi Rabbi, 'The Great Living God', is the supreme God from which all things emanate.

A ganzibra is a high priest in Mandaeism. Tarmidas, or junior priests, rank below the ganzibras.

In Mandaeism, Shitil is an uthra from the World of Light. Shitil is considered to be the Mandaean equivalent of Seth.

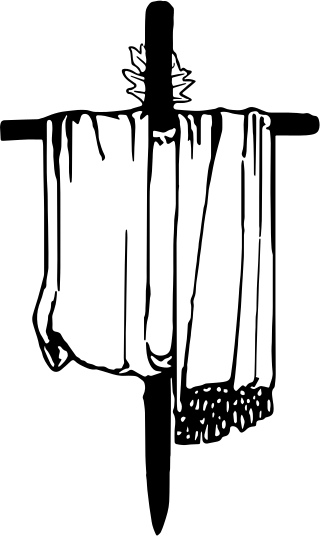

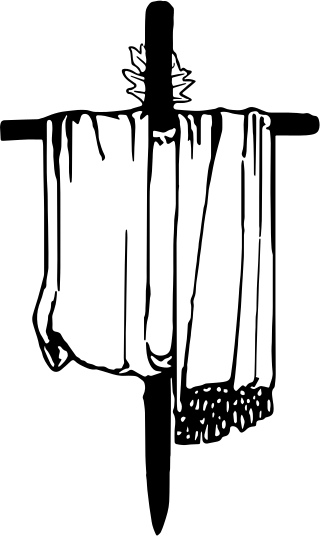

The drabsha or darfash is the symbol of the Mandaean faith. It is typically translated as 'banner'.

The Scroll of the Ancestors is a Mandaean religious text that describes the rituals of the Ṭabahata (ancestors') masiqta, held during the 5-day Parwanaya festival.

In Mandaeism, the klila is a small myrtle wreath or ring used during Mandaean religious rituals. The klila is a female symbol that complements the taga, a white crown which always takes on masculine symbolism.

In Mandaeism, the taga is a white crown traditionally made of silk that is used during Mandaean religious rituals. The taga is a white crown which always takes on masculine symbolism, while the klila is a feminine symbol that complements the taga.

In Mandaeism, Adathan and Yadathan are a pair of uthras who stand at the Gate of Life in the World of Light, praising and worshipping Hayyi Rabbi. In the Ginza Rabba and Qulasta, they are always mentioned together. Book 14 of the Right Ginza mentions Adathan and Yadathan as the guardians of the "first river".

In Mandaeism, rishama (rišama) is a daily ablution ritual. Unlike the masbuta, it does not require the assistance of a priest. Rishama (signing) is performed before prayers and involves washing the face and limbs while reciting specific prayers such as the rushma. It is performed daily, before sunrise, with hair covered and after evacuation of bowels, or before religious ceremonies.

In Mandaeism, a rahma is a daily devotional prayer that is recited during a specific time of the day or specific day of the week. There is a total of approximately 60 rahma prayers, which together make up the Eniania ḏ-Rahmia, a section of the Qulasta that follows the Asut Malkia prayer.

In Mandaeism, a ʿniana or eniana prayer is recited during rituals such as the masiqta and priest initiation ceremonies. They form part of the Qulasta. The rahma prayers are often considered to be a subset of the eniana prayers.

The rushuma is one of the most commonly recited prayers in Mandaeism. It is a "signing" prayer recited during daily ablutions (rishama). The same word can also be used to refer to the ritual signing gesture associated with the prayer.

In Mandaeism, riha is incense used for religious rituals. It is offered by Mandaean priests on a ritual clay tray called kinta in order to establish laufa (communion) between humans in Tibil (Earth) and uthras in the World of Light during rituals such as the masbuta (baptism) and masiqta, as well as during priest initiation ceremonies. Various prayers in the Qulasta are recited when incense is offered. Incense must be offered during specific stages of the typically lengthy and complex rituals.

In Mandaeism, the bshuma is a religious formula that is often written at the beginnings of chapters in Mandaean texts and prayers. The Islamic equivalent is the basmala.

In Mandaeism, misha is anointing sesame oil used during rituals such as the masbuta (baptism) and masiqta, both of which are performed by Mandaean priests.

The Shumhata is one of the most commonly recited prayers in Mandaeism.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to Mandaeism.