Camelot is a legendary castle and court associated with King Arthur. Absent in the early Arthurian material, Camelot first appeared in 12th-century French romances and, since the Lancelot-Grail cycle, eventually came to be described as the fantastic capital of Arthur's realm and a symbol of the Arthurian world.

The estampie is a medieval dance and musical form which was a popular instrumental and vocal form in the 13th and 14th centuries. The name was also applied to poetry.

The Holy Grail is a treasure that serves as an important motif in Arthurian literature. Various traditions describe the Holy Grail as a cup, dish, or stone with miraculous healing powers, sometimes providing eternal youth or sustenance in infinite abundance, often guarded in the custody of the Fisher King and located in the hidden Grail castle. By analogy, any elusive object or goal of great significance may be perceived as a "holy grail" by those seeking such.

King Arthur, according to legends, was a king of Britain. He is a folk hero and a central figure in the medieval literary tradition known as the Matter of Britain.

In Welsh mythology, Gilfaethwy was a son of the goddess Dôn and brother of Gwydion and Arianrhod in the Fourth Branch of the Mabinogi.

Chrétien de Troyes was a French poet and trouvère known for his writing on Arthurian subjects such as Gawain, Lancelot, Perceval and the Holy Grail. Chrétien's chivalric romances, including Erec and Enide, Lancelot, Perceval and Yvain, represent some of the best-regarded works of medieval literature. His use of structure, particularly in Yvain, has been seen as a step towards the modern novel.

Hartmann von Aue, also known as Hartmann von Ouwe, was a German knight and poet. With his works including Erec, Iwein, Gregorius, and Der arme Heinrich, he introduced the Arthurian romance into German literature and, with Wolfram von Eschenbach and Gottfried von Strassburg, was one of the three great epic poets of Middle High German literature.

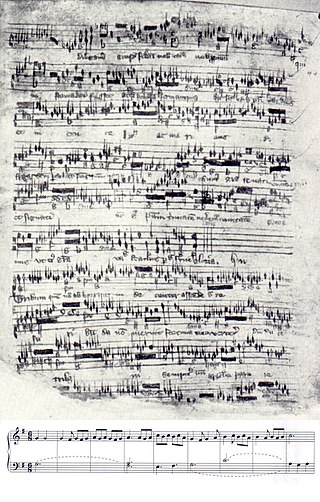

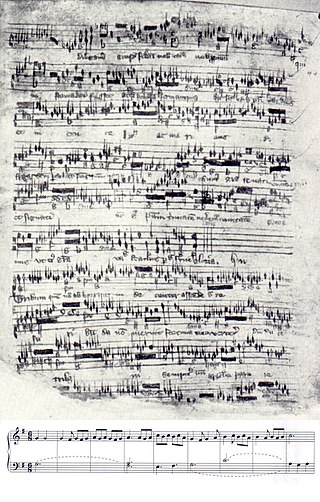

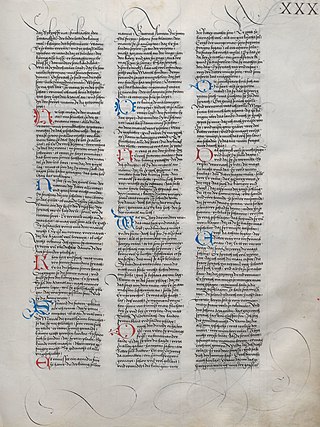

The Robertsbridge Codex (1360) is a music manuscript of the 14th century. It contains the earliest surviving music written specifically for keyboard.

Yvain, the Knight of the Lion is an Arthurian romance by French poet Chrétien de Troyes. It was written c. 1180 simultaneously with Lancelot, the Knight of the Cart, and includes several references to the narrative of that poem. It is a story of knight-errantry, in which the protagonist Yvain is first rejected by his lady for breaking a very important promise, and subsequently performs a number of heroic deeds in order to regain her favour. The poem has been adapted into several other medieval works, including Iwein and Owain, or the Lady of the Fountain.

The Lancelot-Grail Cycle, also known as the Vulgate Cycle or the Pseudo-Map Cycle, is an early 13th-century French Arthurian literary cycle consisting of interconnected prose episodes of chivalric romance originally written in Old French. The work of unknown authorship, presenting itself as a chronicle of actual events, retells the legend of King Arthur by focusing on the love affair between Lancelot and Guinevere, the religious quest for the Holy Grail, and the life of Merlin. The highly influential cycle expands on Robert de Boron's "Little Grail Cycle" and the works of Chrétien de Troyes, previously unrelated to each other, by supplementing them with additional details and side stories, as well as lengthy continuations, while tying the entire narrative together into a coherent single tale.

Perceval, the Story of the Grail is the unfinished fifth verse romance by Chrétien de Troyes, written by him in Old French in the late 12th century. Later authors added 54,000 more lines to the original 9,000 in what are known collectively as the Four Continuations, as well as other related texts. Perceval is the earliest recorded account of what was to become the Quest for the Holy Grail but describes only a golden grail in the central scene, does not call it "holy" and treats a lance, appearing at the same time, as equally significant. Besides the eponymous tale of the grail and the young knight Perceval, the poem and its continuations also tell of the adventures of Gawain and some other knights of King Arthur.

In Arthurian legend, Ywain, also known as Yvain and Owain among other spellings, is a Knight of the Round Table. Tradition often portrays him as the son of King Urien of Gorre and of either the enchantress Modron or the sorceress Morgan le Fay. The historical Owain mab Urien, the basis of the literary character, ruled as the king of Rheged in Britain during the late-6th century.

Erec and Enide is the first of Chrétien de Troyes' five romance poems, completed around 1170. It is one of three completed works by the author. Erec and Enide tells the story of the marriage of the titular characters, as well as the journey they go on to restore Erec's reputation as a knight after he remains inactive for too long. Consisting of about 7000 lines of Old French, the poem is one of the earliest known Arthurian romances in any language, predated only by the Welsh prose narrative Culhwch and Olwen.

Lancelot, the Knight of the Cart, is a 12th-century Old French poem by Chrétien de Troyes, although it is believed that Chrétien did not complete the text himself. It is one of the first stories of the Arthurian legend to feature Lancelot as a prominent character. The narrative tells about the abduction of Queen Guinevere, and is the first text to feature the love affair between Lancelot and Guinevere.

Cligès is a poem by the medieval French poet Chrétien de Troyes, dating from around 1176. It is the second of his five Arthurian romances; Erec and Enide, Cligès, Yvain, Lancelot and Perceval. The poem tells the story of the knight Cligès and his love for his uncle's wife, Fenice.

Blanchefleur is the name of a number of characters in literature of the High Middle Ages. Except for in Perceval, the Story of the Grail, Blanchefleur is typically a character who reflects her name—an image of purity and idealized beauty.

Italian folk dance has been an integral part of Italian culture for centuries. Dance has been a continuous thread in Italian life from Dante through the Renaissance, the advent of the tarantella in Southern Italy, and the modern revivals of folk music and dance.

Erec is a Middle High German poem written in rhyming couplets by Hartmann von Aue. It is thought to be the earliest of Hartmann's narrative works and dates from around 1185. An adaptation of Chrétien de Troyes' Erec et Enide, it is the first Arthurian Romance in German.

La Mule sans frein or La Demoiselle à la mule is a short romance dating from the late 12th century or early 13th century. It comprises 1,136 lines in octosyllabic couplets, written in Old French. Its author names himself as Païen de Maisières, but critics disagree as to whether this was his real name or a pseudonym. La Mule is an Arthurian romance relating the adventures, first of Sir Kay, then of Sir Gawain, in attempting to restore to its rightful owner a stolen bridle. It is notable for its early use of the "beheading game" theme, which later reappeared in the Middle English romance Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. It is sometimes seen as a skit or burlesque on earlier romances, especially those of Chrétien de Troyes, but it has also been suggested that it might have been written by Chrétien himself.

In the Middle High German (MHG) period (1050–1350) the courtly romance, written in rhyming couplets, was the dominant narrative genre in the literature of the noble courts, and the romances of Hartmann von Aue, Gottfried von Strassburg and Wolfram von Eschenbach, written c. 1185 – c. 1210, are recognized as classics.