| Old Catalan | |

|---|---|

| Medieval Catalan | |

| catalanesc, catalanesch, romanç | |

| Pronunciation | [katalaˈnesk] , [kətələˈnəsk] , [roˈmãnt͡s] |

| Region | Principality of Catalonia, Kingdom of Valencia, Balearic islands, Sardinia |

| Era | 9th–16th century, evolved into Modern Catalan by the 16th century [1] |

Early forms | |

| Latin | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | oldc1251 |

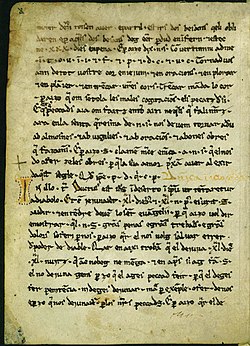

Probable linguistic expansion of Old Catalan from the 11th to 15th centuries | |

Old Catalan, also known as Medieval Catalan, is the modern denomination for Romance varieties that during the Middle Ages were spoken in territories that spanned roughly the territories of the Principality of Catalonia, the Kingdom of Valencia, the Balearic Islands, and the island of Sardinia; all of them then part of the Crown of Aragon. These varieties were part of a dialect continuum with what today is called Old Occitan that reached the Loire Valley in the north and Northern Italy in the east. Consequently, Old Catalan can be considered a dialect group of Old Occitan,[ citation needed ] [2] or be classified as an Occitano-Romance variety side by side with Old Occitan (also known as Old Provençal). [3]

Contents

- Phonology

- Consonants

- Vowels

- Orthography

- History

- Early Middle Ages

- Late Middle Ages

- See also

- References

- Bibliography

The modern separation of Catalan and Occitan should not be confused with a clear separation between the languages in the mindset of their speakers historically. From the 8th century to the 13th century, there was no clear sociolinguistic distinction between Occitania and Catalonia. For instance, the Provençal troubadour, Albertet de Sestaró, says: "Monks, tell me which according to your knowledge are better: the French or the Catalans? And here I shall put Gascony, Provence, Limousin, Auvergne and Viennois while there shall be the land of the two kings." (Monges, causetz, segons vostre siensa qual valon mais, catalan ho francés?/ E met de sai Guascuenha e Proensa/ E lemozí, alvernh’ e vianés/ E de lai met la terra dels dos reis.)[ citation needed ] In Marseille, a typical Provençal song is called "Catalan song". [4] Moreover, the dialects of Modern Catalan were still considered to be part of the same language as the dialects of Occitan in the 19th century, when Catalans still could call their language Llengua llemosina, [5] using the name of the Limousin dialect as a metonymy for Occitan.