Eurypterids, often informally called sea scorpions, are a group of extinct arthropods that form the order Eurypterida. The earliest known eurypterids date to the Darriwilian stage of the Ordovician period 467.3 million years ago. The group is likely to have appeared first either during the Early Ordovician or Late Cambrian period. With approximately 250 species, the Eurypterida is the most diverse Paleozoic chelicerate order. Following their appearance during the Ordovician, eurypterids became major components of marine faunas during the Silurian, from which the majority of eurypterid species have been described. The Silurian genus Eurypterus accounts for more than 90% of all known eurypterid specimens. Though the group continued to diversify during the subsequent Devonian period, the eurypterids were heavily affected by the Late Devonian extinction event. They declined in numbers and diversity until becoming extinct during the Permian–Triassic extinction event 251.9 million years ago.

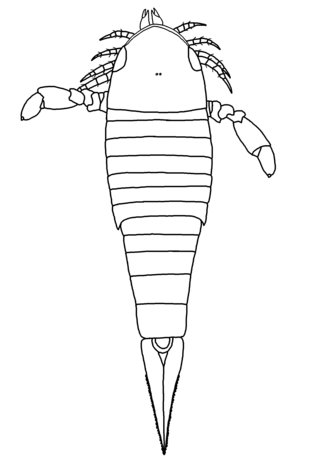

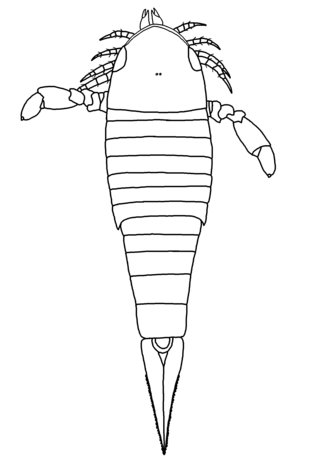

Pterygotus is a genus of giant predatory eurypterid, a group of extinct aquatic arthropods. Fossils of Pterygotus have been discovered in deposits ranging in age from Middle Silurian to Late Devonian, and have been referred to several different species. Fossils have been recovered from four continents; Australia, Europe, North America and South America, which indicates that Pterygotus might have had a nearly cosmopolitan (worldwide) distribution. The type species, P. anglicus, was described by Swiss naturalist Louis Agassiz in 1839, who gave it the name Pterygotus, meaning "winged one". Agassiz mistakenly believed the remains were of a giant fish; he would only realize the mistake five years later in 1844.

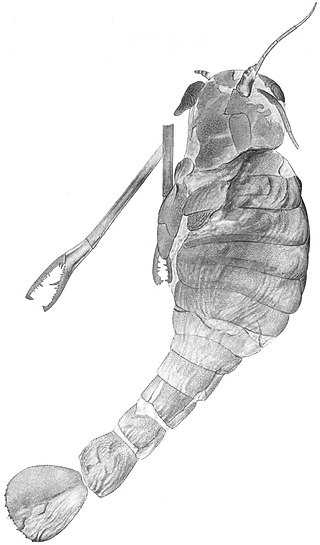

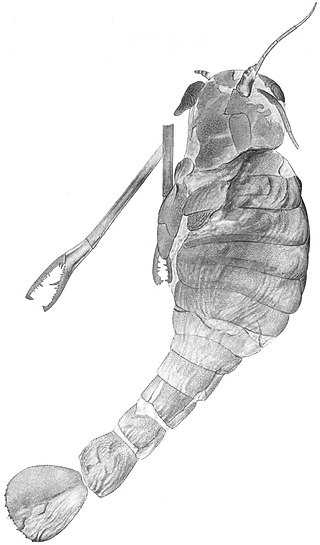

Slimonia is a genus of eurypterid, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. Fossils of Slimonia have been discovered in deposits of Silurian age in South America and Europe. Classified as part of the family Slimonidae alongside the related Salteropterus, the genus contains three valid species, S. acuminata from Lesmahagow, Scotland, S. boliviana from Cochabamba, Bolivia and S. dubia from the Pentland Hills of Scotland and one dubious species, S. stylops, from Herefordshire, England. The generic name is derived from and honors Robert Slimon, a fossil collector and surgeon from Lesmahagow.

Carcinosoma is a genus of eurypterid, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. Fossils of Carcinosoma are restricted to deposits of late Silurian age. Classified as part of the family Carcinosomatidae, which the genus lends its name to, Carcinosoma contains seven species from North America and Great Britain.

Hughmilleria is a genus of eurypterid, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. Fossils of Hughmilleria have been discovered in deposits of the Silurian age in China and the United States. Classified as part of the basal family Hughmilleriidae, the genus contains three species, H. shawangunk from the eastern United States, H. socialis from Pittsford, New York, and H. wangi from Hunan, China. The genus is named in honor of the Scottish geologist Hugh Miller.

Acutiramus is a genus of giant predatory eurypterid, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. Fossils of Acutiramus have been discovered in deposits of Late Silurian to Early Devonian age. Seven species have been described, five from North America and two from the Czech Republic. The generic name derives from Latin acuto and Latin ramus ("branch"), referring to the acute angle of the final tooth of the claws relative to the rest of the claw.

Jaekelopterus is a genus of predatory eurypterid, a group of extinct aquatic arthropods. Fossils of Jaekelopterus have been discovered in deposits of Early Devonian age, from the Pragian and Emsian stages. There are two known species: the type species J. rhenaniae from brackish to fresh water strata in the Rhineland, and J. howelli from estuarine strata in Wyoming. The generic name combines the name of German paleontologist Otto Jaekel, who described the type species, and the Greek word πτερόν (pteron) meaning "wing".

Alkenopterus is a genus of prehistoric eurypterid classified as part of the family Onychopterellidae. The genus contains two species, A. brevitelson and A. burglahrensis, both from the Devonian of Germany.

Salteropterus is a genus of eurypterid, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. Fossils of Salteropterus have been discovered in deposits of Late Silurian age in Britain. Classified as part of the family Slimonidae, the genus contains one known valid species, S. abbreviatus, which is known from fossils discovered in Herefordshire, England, and a dubious species, S. longilabium, with fossils discovered in Leintwardine, also in Herefordshire. The generic name honours John William Salter, who originally described S. abbreviatus as a species of Eurypterus in 1859.

Erettopterus is a genus of large predatory eurypterid, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. Fossils of Erettopterus have been discovered in deposits ranging from Early Silurian to the Early Devonian, and have been referred to several different species. Fossils have been recovered from two continents; Europe and North America. The genus name is composed by the Ancient Greek words ἐρέττω (eréttō), which means "rower", and πτερόν (pterón), which means "wing", and therefore, "rower wing".

Unionopterus is a genus of eurypterid, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods commonly known as "sea scorpions". Fossils have been registered from the Early Carboniferous period. The genus contains only one species, U. anastasiae, recovered from deposits of Tournaisian to Viséan stages in Kazakhstan. Known from one single specimen which was described in a publication of Russian language with poor illustrations, Unionopterus' affinities are extremely poorly known.

Pterygotidae is a family of eurypterids, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. They were members of the superfamily Pterygotioidea. Pterygotids were the largest known arthropods to have ever lived with some members of the family, such as Jaekelopterus and Acutiramus, exceeding 2 metres (6.6 ft) in length. Their fossilized remains have been recovered in deposits ranging in age from 428 to 372 million years old.

Carcinosomatidae is a family of eurypterids, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. They were members of the superfamily Carcinosomatoidea, also named after Carcinosoma. Fossils of carcinosomatids have been found in North America, Europe and Asia, the family possibly having achieved a worldwide distribution, and range in age from the Late Ordovician to the Early Devonian. They were among the most marine eurypterids, known almost entirely from marine environments.

Pterygotioidea is a superfamily of eurypterids, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. Pterygotioids were the most derived members of the infraorder Diploperculata and the sister group of the adelophthalmoid eurypterids. The group includes the basal and small hughmilleriids, the larger and specialized slimonids and the famous pterygotids which were equipped with robust and powerful cheliceral claws.

Adelophthalmidae is a family of eurypterids, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. Adelophthalmidae is the only family classified as part of the superfamily Adelophthalmoidea, which in turn is classified within the infraorder Diploperculata in the suborder Eurypterina.

Hughmilleriidae is a family of eurypterids, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. The hughmilleriids were the most basal members of the superfamily Pterygotioidea, in contrast with the more derived families Pterygotidae and Slimonidae. Despite their classification as pterygotioids, the hughmilleriids possessed several characteristics shared with other eurypterid groups, such as the lanceolate telson.

Herefordopterus is a genus of eurypterid, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. Herefordopterus is classified as part of the family Hughmilleriidae, a basal family in the highly derived Pterygotioidea superfamily of eurypterids. Fossils of the single and type species, H. banksii, have been discovered in deposits of Silurian age in Herefordshire and Shropshire, England. The genus is named after Herefordshire, where most of the Herefordopterus fossils have been found. The specific epithet honors Richard Banks, who found several well-preserved specimens, including the first Herefordopterus fossils.

Necrogammarus salweyi is the binomial name applied to an arthropod fossil discovered in Herefordshire, England. The fossil represents a fragmentary section of the underside and an appendage of a pterygotid eurypterid, a group of large and predatory aquatic arthropods that lived from the late Silurian to the late Devonian. The Necrogammarus fossil is Late Silurian in age and its generic name means "dead lobster", deriving from Ancient Greek νεκρός and Latin gammarus ("lobster").

Ciurcopterus is a genus of eurypterid, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. Fossils of Ciurcopterus have been discovered in deposits of Late Silurian age in North America. Classified as part of the family Pterygotidae, the genus contains two species, C. sarlei from Pittsford, New York and C. ventricosus from Kokomo, Indiana. The genus is named in honor of Samuel J. Ciurca, Jr., who has contributed significantly to eurypterid research by discovering a large amount of eurypterid specimens, including the four specimens used to describe Ciurcopterus itself.

This timeline of eurypterid research is a chronologically ordered list of important fossil discoveries, controversies of interpretation, and taxonomic revisions of eurypterids, a group of extinct aquatic arthropods closely related to modern arachnids and horseshoe crabs that lived during the Paleozoic Era.