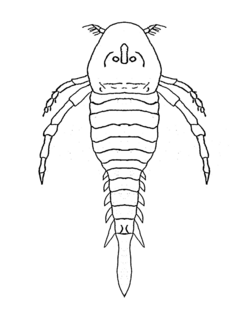

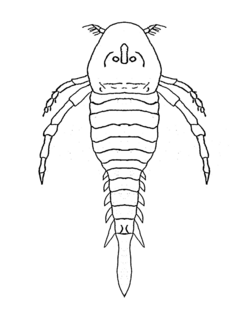

Eurypterids, often informally called sea scorpions, are a group of extinct arthropods that form the order Eurypterida. The earliest known eurypterids date to the Darriwilian stage of the Ordovician period 467.3 million years ago. The group is likely to have appeared first either during the Early Ordovician or Late Cambrian period. With approximately 250 species, the Eurypterida is the most diverse Paleozoic chelicerate order. Following their appearance during the Ordovician, eurypterids became major components of marine faunas during the Silurian, from which the majority of eurypterid species have been described. The Silurian genus Eurypterus accounts for more than 90% of all known eurypterid specimens. Though the group continued to diversify during the subsequent Devonian period, the eurypterids were heavily affected by the Late Devonian extinction event. They declined in numbers and diversity until becoming extinct during the Permian–Triassic extinction event 251.9 million years ago.

Stylonurina is one of two suborders of eurypterids, a group of extinct arthropods commonly known as "sea scorpions". Members of the suborder are collectively and informally known as "stylonurine eurypterids" or "stylonurines". They are known from deposits primarily in Europe and North America, but also in Siberia.

Hibbertopterus is a genus of eurypterid, a group of extinct aquatic arthropods. Fossils of Hibbertopterus have been discovered in deposits ranging from the Devonian period in Belgium, Scotland and the United States to the Carboniferous period in Scotland, Ireland, the Czech Republic and South Africa. The type species, H. scouleri, was first named as a species of the significantly different Eurypterus by Samuel Hibbert in 1836. The generic name Hibbertopterus, coined more than a century later, combines his name and the Greek word πτερόν (pteron) meaning "wing".

Megarachne is a genus of eurypterid, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. Fossils of Megarachne have been discovered in deposits of Late Carboniferous age, from the Gzhelian stage, in San Luis, Argentina. The fossils of the single and type species M. servinei have been recovered from deposits that had once been a freshwater environment. The generic name, composed of the Ancient Greek μέγας (megas) meaning "great" and Ancient Greek ἀράχνη (arachne) meaning "spider", translates to "great spider", because the fossil was misidentified as a large prehistoric spider.

Drepanopterus is an extinct genus of eurypterid and the only member of the family Drepanopteridae within the Mycteropoidea superfamily. There are currently three species assigned to the genus. The genus has historically included more species, with nine species associated with the genus Drepanopterus, however five of these have since been proven to be synonyms of pre-existing species, assigned to their own genera, or found to be based on insubstantial fossil data. The holotype of one species proved to be a lithic clast.

Campylocephalus is a genus of eurypterid, a group of extinct aquatic arthropods. Fossils of Campylocephalus have been discovered in deposits ranging from the Carboniferous period in the Czech Republic to the Permian period of Russia. The generic name is composed of the Greek words καμπύλος (kampýlos), meaning "curved", and κεφαλή (kephalē), meaning "head".

Stylonuridae is a family of eurypterids, an extinct group of chelicerate arthropods commonly known as "sea scorpions". The family is one of two families contained in the superfamily Stylonuroidea, which in turn is one of four superfamilies classified as part of the suborder Stylonurina.

The Rhenopteridae are a family of eurypterids, an extinct group of chelicerate arthropods commonly known as "sea scorpions". The family is the only family currently contained in the superfamily Rhenopteroidea, one of four superfamilies classified as part of the suborder Stylonurina.

Mycteroptidae are a family of eurypterids, a group of extinct chelicerate arthropods commonly known as "sea scorpions". The family is one of three families contained in the superfamily Mycteropoidea, which in turn is one of four superfamilies classified as part of the suborder Stylonurina.

Pterygotioidea is a superfamily of eurypterids, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. Pterygotioids were the most derived members of the infraorder Diploperculata and the sister group of the adelophthalmoid eurypterids. The group includes the basal and small hughmilleriids, the larger and specialized slimonids and the famous pterygotids which were equipped with robust and powerful cheliceral claws.

Stylonuroidea is an extinct superfamily of eurypterids, an extinct group of chelicerate arthropods commonly known as "sea scorpions". It is one of four superfamilies classified as part of the suborder Stylonurina.

The Parastylonuridae are a family of eurypterids, an extinct group of chelicerate arthropods commonly known as "sea scorpions". The family is one of two families contained in the superfamily Stylonuroidea, which in turn is one of four superfamilies classified as part of the suborder Stylonurina.

Kokomopteroidea is an extinct superfamily of eurypterids, an extinct group of chelicerate arthropods commonly known as "sea scorpions". It is one of four superfamilies classified as part of the suborder Stylonurina. Kokomopteroids have been recovered from deposits of Early Silurian to Late Devonian age in the United States and the United Kingdom.

The Kokomopteridae are a family of eurypterids, an extinct group of chelicerate arthropods commonly known as "sea scorpions". The family is one of two families contained in the superfamily Kokomopteroidea, which in turn is one of four superfamilies classified as part of the suborder Stylonurina.

The Hardieopteridae are a family of eurypterids, an extinct group of chelicerate arthropods commonly known as "sea scorpions". The family is one of two families contained in the superfamily Kokomopteroidea, which in turn is one of four superfamilies classified as part of the suborder Stylonurina. Hardieopterids have been recovered from deposits of Early Silurian to Late Devonian age in the United States and the United Kingdom.

Adelophthalmidae is a family of eurypterids, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. Adelophthalmidae is the only family classified as part of the superfamily Adelophthalmoidea, which in turn is classified within the infraorder Diploperculata in the suborder Eurypterina.

Eurypterina is one of two suborders of eurypterids, an extinct group of chelicerate arthropods commonly known as "sea scorpions". Eurypterine eurypterids are sometimes informally known as "swimming eurypterids". They are known from fossil deposits worldwide, though primarily in North America and Europe.

Mycteropoidea is an extinct superfamily of eurypterids, an extinct group of chelicerate arthropods commonly known as "sea scorpions". It is one of four superfamilies classified as part of the suborder Stylonurina. Mycteropoids have been recovered from Europe, Russia, South America and South Africa. Mycteropoid specimens are often fragmentary, making it difficult to establish relationships between the included taxa. Only two mycteropoid taxa are known from reasonable complete remains, Hibbertopterus scouleri and H. wittebergensis.

Vernonopterus is a genus of eurypterid, a group of extinct aquatic arthropods. Fossils of Vernonopterus have been discovered in deposits of the Carboniferous period in Scotland. The name of the genus derives from the location where the only known fossil has been discovered, Mount Vernon near Airdrie in Lanarkshire, Scotland. A single species of Vernonopterus is recognized, V. minutisculptus, based on fragmentary fossilized tergites, segments on the upper side of the abdomen. The species name minutisculptus refers to the ornamentation of scales that covers the entirety of the preserved parts of the eurypterid.

Slimonidae is a family of eurypterids, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. Slimonids were members of the superfamily Pterygotioidea and the family most closely related to the derived pterygotid eurypterids, which are famous for their cheliceral claws and great size. Many characteristics of the Slimonidae, such as their flattened and expanded telsons, support a close relationship between the two groups.