Ants are eusocial insects of the family Formicidae and, along with the related wasps and bees, belong to the order Hymenoptera. Ants evolved from vespoid wasp ancestors in the Cretaceous period. More than 13,800 of an estimated total of 22,000 species have been classified. They are easily identified by their geniculate (elbowed) antennae and the distinctive node-like structure that forms their slender waists.

Trophallaxis is the transfer of food or other fluids among members of a community through mouth-to-mouth (stomodeal) or anus-to-mouth (proctodeal) feeding. Along with nutrients, trophallaxis can involve the transfer of molecules such as pheromones, organisms such as symbionts, and information to serve as a form of communication. Trophallaxis is used by some birds, gray wolves, vampire bats, and is most highly developed in eusocial insects such as ants, wasps, bees, and termites.

Fire ants are several species of ants in the genus Solenopsis, which includes over 200 species. Solenopsis are stinging ants, and most of their common names reflect this, for example, ginger ants and tropical fire ants. Many of the names shared by this genus are often used interchangeably to refer to other species of ant, such as the term red ant, mostly because of their similar coloration despite not being in the genus Solenopsis. Both Myrmica rubra and Pogonomyrmex barbatus are common examples of non-Solenopsis ants being termed red ants.

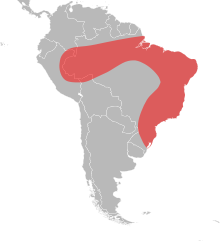

Solenopsis invicta, the fire ant, or red imported fire ant (RIFA), is a species of ant native to South America. A member of the genus Solenopsis in the subfamily Myrmicinae, it was described by Swiss entomologist Felix Santschi as a variant of S. saevissima in 1916. Its current specific name invicta was given to the ant in 1972 as a separate species. However, the variant and species were the same ant, and the name was preserved due to its wide use. Though South American in origin, the red imported fire ant has been accidentally introduced in Australia, New Zealand, several Asian and Caribbean countries, Europe and the United States. The red imported fire ant is polymorphic, as workers appear in different shapes and sizes. The ant's colours are red and somewhat yellowish with a brown or black gaster, but males are completely black. Red imported fire ants are dominant in altered areas and live in a wide variety of habitats. They can be found in rainforests, disturbed areas, deserts, grasslands, alongside roads and buildings, and in electrical equipment. Colonies form large mounds constructed from soil with no visible entrances because foraging tunnels are built and workers emerge far away from the nest.

Myrmecia is a genus of ants first established by Danish zoologist Johan Christian Fabricius in 1804. The genus is a member of the subfamily Myrmeciinae of the family Formicidae. Myrmecia is a large genus of ants, comprising at least 93 species that are found throughout Australia and its coastal islands, while a single species is only known from New Caledonia. One species has been introduced out of its natural distribution and was found in New Zealand in 1940, but the ant was last seen in 1981. These ants are commonly known as bull ants, bulldog ants or jack jumper ants, and are also associated with many other common names. They are characterized by their extreme aggressiveness, ferocity, and painful stings. Some species are known for the jumping behavior they exhibit when agitated.

The pharaoh ant is a small (2 mm) yellow or light brown, almost transparent ant notorious for being a major indoor nuisance pest, especially in hospitals. A cryptogenic species, it has now been introduced to virtually every area of the world, including Europe, the Americas, Australasia and Southeast Asia. It is a major pest in the United States, Australia, and Europe. The ant's common name is possibly derived from the mistaken belief that it was one of the Egyptian (pharaonic) plagues.

The name army ant (or legionary ant or marabunta) is applied to over 200 ant species in different lineages. Because of their aggressive predatory foraging groups, known as "raids", a huge number of ants forage simultaneously over a limited area.

Eciton burchellii is a species of New World army ant in the genus Eciton. This species performs expansive, organized swarm raids that give it the informal name, Eciton army ant. This species displays a high degree of worker polymorphism. Sterile workers are of four discrete size-castes: minors, medias, porters (sub-majors), and soldiers (majors). Soldiers have much larger heads and specialized mandibles for defense. In lieu of underground excavated nests, colonies of E. burchellii form temporary living nests known as bivouacs, which are composed of hanging live worker bodies and which can be disassembled and relocated during colony emigrations. Eciton burchellii colonies cycle between stationary phases and nomadic phases when the colony emigrates nightly. These alternating phases of emigration frequency are governed by coinciding brood developmental stages. Group foraging efforts known as "raids" are maintained by the use of pheromones, can be 200 metres (660 ft) long, and employ up to 200,000 ants. Workers are also adept at making living structures out of their own bodies to improve efficiency of moving as a group across the forest floor while foraging or emigrating. Workers can fill "potholes" in the foraging trail with their own bodies, and can also form living bridges. Numerous antbirds prey on the Eciton burchellii by using their raids as a source of food. In terms of geographical distribution, this species is found in the Amazon jungle and Central America.

Nothomyrmecia, also known as the dinosaur ant or dawn ant, is an extremely rare genus of ants consisting of a single species, Nothomyrmecia macrops. These ants live in South Australia, nesting in old-growth mallee woodland and Eucalyptus woodland. The full distribution of Nothomyrmecia has never been assessed, and it is unknown how widespread the species truly is; its potential range may be wider if it does favour old-growth mallee woodland. Possible threats to its survival include habitat destruction and climate change. Nothomyrmecia is most active when it is cold because workers encounter fewer competitors and predators such as Camponotus and Iridomyrmex, and it also increases hunting success. Thus, the increase of temperature may prevent them from foraging and very few areas would be suitable for the ant to live in. As a result, the IUCN lists the ant as Critically Endangered.

Solenopsis molesta is the best known species of Solenopsisthief ants. They get their names from their habit of nesting close to other ant nests, from which they steal food. They are also called grease ants because they are attracted to grease. Nuptial flight in this species occur from late July through early fall.

The tawny crazy ant or Rasberry crazy ant, Nylanderia fulva, is an ant originating in South America. Like the longhorn crazy ant, this species is called "crazy ant" because of its quick, unpredictable movements. It is sometimes called the "Rasberry crazy ant" in Texas after the exterminator Tom Rasberry, who noticed that the ants were increasing in numbers in 2002. Scientists have reorganised the genera taxonomy within this clade of ants, and now it is identified as Nylanderia fulva.

The green-head ant is a species of ant that is endemic to Australia. It was described by British entomologist Frederick Smith in 1858 as a member of the genus Rhytidoponera in the subfamily Ectatomminae. These ants measure between 5 and 7 mm. The queens and workers look similar, differing only in size, with the males being the smallest. They are well known for their distinctive metallic appearance, which varies from green to purple or even reddish-violet. Among the most widespread of all insects in Australia, green-head ants are found in almost every Australian state, but are absent in Tasmania. They have also been introduced in New Zealand, where several populations have been established.

The longhorn crazy ant, also known as the black crazy ant, is a species of small, dark-coloured insect in the family Formicidae. These ants are commonly called "crazy ants" because instead of following straight lines, they dash around erratically. They have a broad distribution, including much of the tropics and subtropics, and are also found in buildings in more temperate regions, making them one of the most widespread ant species in the world. This species, as well as all others in the ant subfamily Formicinae, cannot sting. However, this species can fire/shoot a formic acid spray from its abdomen when under attack by other insects or attacking other insects. When the longhorn crazy ant bends its abdomen while aiming at an enemy insect, it is typically shooting its hard-to-see acid.

Pogonomyrmex occidentalis, or the western harvester ant, is a species of ant that inhabits the deserts and arid grasslands of the American West at or below 6,300 feet (1,900 m). Like other harvester ants in the genus Pogonomyrmex, it is so called because of its habit of collecting edible seeds and other food items. The specific epithet "occidentalis", meaning "of the west", refers to the fact that it is characteristic of the interior of the Western United States; its mounds of gravel, surrounded by areas denuded of plant life, are a conspicuous feature of rangeland. When numerous, they may cause such loss of grazing plants and seeds, as to constitute both a severe ecological and economic burden. They have a painful and venomous sting.

Trail pheromones are semiochemicals secreted from the body of an individual to affect the behavior of another individual receiving it. Trail pheromones often serve as a multi purpose chemical secretion that leads members of its own species towards a food source, while representing a territorial mark in the form of an allomone to organisms outside of their species. Specifically, trail pheromones are often incorporated with secretions of more than one exocrine gland to produce a higher degree of specificity. Considered one of the primary chemical signaling methods in which many social insects depend on, trail pheromone deposition can be considered one of the main facets to explain the success of social insect communication today. Many species of ants, including those in the genus Crematogaster use trail pheromones.

Dinoponera is a strictly South American genus of ant in the subfamily Ponerinae, commonly called tocandiras or giant Amazonian ants. These ants are generally less well known than Paraponera clavata, the bullet ant, yet Dinoponera females may surpass 3–4 cm (1.2–1.6 in) in total body length, making them among the largest ants in the world.

Formica truncorum is a species of wood ant from the genus Formica. It is distributed across a variety of locations worldwide, including central Europe and Japan. Workers can range from 3.5 to 9.0mm and are uniquely characterized by small hairs covering their entire bodies. Like all other ants, F. truncorum is eusocial and demonstrates many cooperative behaviors that are unique to its order. Colonies are either monogynous, with one queen, or polygynous, with many queens, and these two types of colonies differ in many characteristics.

Pogonomyrmex badius, or the Florida harvester ant, is a species of harvester ant in the genus Pogonomyrmex. It is the only Pogonomyrmex species found on the east coast of the United States and the only one in North America known to be polymorphic. The Florida Harvester ant is commonly found in Florida scrub and other similar habitats within the Atlantic coastal plain.

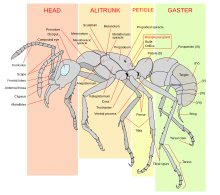

This is a glossary of terms used in the descriptions of ants.

Symphiles are insects or other organisms which live as welcome guests in the nest of a social insect by which they are fed and guarded. The relationship between the symphile and host may be symbiotic, inquiline or parasitic.