In amniotes, the clitoris is a female sex organ. In humans, it is the vulva's most erogenous area and generally the primary anatomical source of female sexual pleasure. The clitoris is a complex structure, and its size and sensitivity can vary. The visible portion, the glans, of the clitoris is typically roughly the size and shape of a pea and is estimated to have at least 8,000 nerve endings.

Orgasm or sexual climax is the sudden release of accumulated sexual excitement during the sexual response cycle, characterized by intense sexual pleasure resulting in rhythmic, involuntary muscular contractions in the pelvic region. Orgasms are controlled by the involuntary or autonomic nervous system and experienced by both males and females; the body's response includes muscular spasms, a general euphoric sensation, and, frequently, body movements and vocalizations. The period after orgasm is typically a relaxing experience, after the release of the neurohormones oxytocin and prolactin, as well as endorphins.

The G-spot, also called the Gräfenberg spot, is characterized as an erogenous area of the vagina that, when stimulated, may lead to strong sexual arousal, powerful orgasms and potential female ejaculation. It is typically reported to be located 5–8 cm (2–3 in) up the front (anterior) vaginal wall between the vaginal opening and the urethra and is a sensitive area that may be part of the female prostate.

An erogenous zone is an area of the human body that has heightened sensitivity, the stimulation of which may generate a sexual response such as relaxation, sexual fantasies, sexual arousal, and orgasm.

A trans man is a man who was assigned female at birth. Trans men have a male gender identity, and many trans men undergo medical and social transition to alter their appearance in a way that aligns with their gender identity or alleviates gender dysphoria.

Gender-affirming surgery for female-to-male transgender people includes a variety of surgical procedures that alter anatomical traits to provide physical traits more comfortable to the trans man's male identity and functioning.

Gender-affirming surgery for male-to-female transgender women or transfeminine non-binary people describes a variety of surgical procedures that alter the body to provide physical traits more comfortable and affirming to an individual's gender identity and overall functioning.

Gender transition is the process of affirming and expressing one's internal sense of gender, rather than the gender assigned to them at birth. It is the recommended course of treatment for individuals struggling with gender dysphoria, providing improved mental health outcomes in the majority of people.

Emasculation is the removal of the external male sex organs, which includes both the penis and the scrotum, the latter of which contains the testicles. It is distinct from castration, where only the testicles are removed. Although the terms are sometimes used interchangeably, the potential medical consequences of emasculation are more extensive due to the complications arising from the removal of the penis. There are a range of religious, cultural, punitive, and personal reasons why someone may choose to emasculate themselves or another person.

Scrotoplasty, also known as oscheoplasty, is a type of surgery to create or repair the scrotum. Scientific research for male genital plastic surgery such as scrotoplasty began to develop in the early 1900s. The development of testicular implants began in 1940 made from materials outside of what is used today. Today, testicular implants are created from saline or gel filled silicone rubber. There are a variety of reasons why scrotoplasty is done. Some transgender men and intersex or non-binary people who were assigned female at birth may choose to have this surgery to create a scrotum, as part of their transition. Other reasons for this procedure include addressing issues with the scrotum due to birth defects, aging, or medical conditions such as infection. For newborn males with penoscrotal defects such as webbed penis, a condition in which the penile shaft is attached to the scrotum, scrotoplasty can be performed to restore normal appearance and function. For older male adults, the scrotum may extend with age. Scrotoplasty or scrotal lift can be performed to remove the loose, excess skin. Scrotoplasty can also be performed for males who undergo infection, necrosis, traumatic injury of the scrotum.

Sexuality in transgender individuals encompasses all the issues of sexuality of other groups, including establishing a sexual identity, learning to deal with one's sexual needs, and finding a partner, but may be complicated by issues of gender dysphoria, side effects of surgery, physiological and emotional effects of hormone replacement therapy, psychological aspects of expressing sexuality after medical transition, or social aspects of expressing their gender.

A clitoral pump is a sex toy designed for sexual pleasure that is applied to the clitoris to create suction and increase blood flow and sensitivity. A clitoral pump is designed to be used on the entire external clitoris including the clitoral hood. Other designs of pump exist for the labia, the entire vulva and, in some cases, the nipples.

Non-penetrative sex or outercourse is sexual activity that usually does not include sexual penetration, but some forms, particularly when termed outercourse, include penetrative aspects, that may result from forms of fingering or oral sex. It generally excludes the penetrative aspects of vaginal, anal, or oral sex, but includes various forms of sexual and non-sexual activity, such as frottage, manual sex, mutual masturbation, kissing, or hugging.

The one-sex and two-sex theories are two models of human anatomy or fetal development discussed in Thomas Laqueur's book Making Sex: Body and Gender from the Greeks to Freud. Laqueur theorizes that a fundamental change in attitudes toward human sexual anatomy occurred in Europe in the 18th and 19th centuries. He draws from scholars such as Aristotle and Galen to argue that prior to the eighteenth century, women and men were viewed as two different forms of one essential sex: that is, women were seen to possess the same fundamental reproductive structure as men, the only difference being that female genitalia was inside the body, not outside of it. Anatomists saw the vagina as an interior penis, the labia as foreskin, the uterus as scrotum, and the ovaries as testicles. Laqueur uses the theory of interconvertible bodily fluids as evidence for the one-sex model. However, he claims that around the 18th century, the dominant view became that of two sexes directly opposite to each other. In his view, the departure from a one-sex model is largely because of political shifts which challenged the way women's sexuality came to be seen. One result of this was the emerging view of the female orgasm as nonessential to conception after the eighteenth century. Women and men began to be seen as opposites and each sex was compared in relation to the other. Freud's work further perpetuated the sexual socialization of women by dictating how they should feel pleasure.

Penis envy is a stage in Sigmund Freud's theory of female psychosexual development, in which young girls experience anxiety upon realization that they do not have a penis. Freud considered this realization a defining moment in a series of transitions toward a mature female sexuality. In Freudian theory, the penis envy stage begins the transition from attachment to the mother to competition with the mother for the attention and affection of the father. The young boy's realization that women do not have a penis is thought to result in castration anxiety.

LGBTQ linguistics is the study of language as used by members of LGBTQ communities. Related or synonymous terms include lavender linguistics, advanced by William Leap in the 1990s, which "encompass[es] a wide range of everyday language practices" in LGBTQ communities, and queer linguistics, which refers to the linguistic analysis concerning the effect of heteronormativity on expressing sexual identity through language. The former term derives from the longtime association of the color lavender with LGBTQ communities. "Language", in this context, may refer to any aspect of spoken or written linguistic practices, including speech patterns and pronunciation, use of certain vocabulary, and, in a few cases, an elaborate alternative lexicon such as Polari.

Genital regeneration encompasses various forms of treatment for genital anomalies. The goal of these treatments is to restore form and function to male and female genitalia by taking advantage of innate responses in the body. In order to do this, doctors have experimented with stem cells and extracellular matrix to provide a framework for regenerating missing structures. More research is needed to successfully move the science from laboratory trials to routine procedures.

The Phall-O-meter is a satirical measure that critiques medical standards for normal male and female phalluses. The tool was developed by Kiira Triea based on a concept by Suzanne Kessler and is used to demonstrate concerns with the medical treatment of intersex bodies.

Lal Zimman is an American linguist who works on sociocultural linguistics, sociophonetics, language, gender and identity, and transgender linguistics.

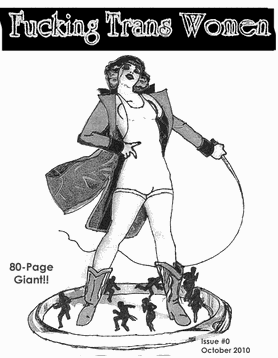

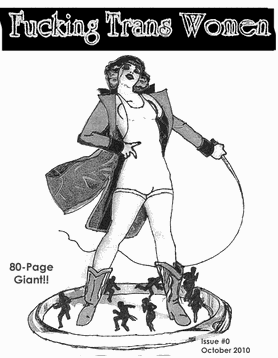

Fucking Trans Women (FTW) is a zine created by Mira Bellwether. A single 80-page issue, numbered "#0", was published in October 2010 and republished in 2013 as Fucking Trans Women: A Zine About the Sex Lives of Trans Women; further issues were planned, but none had been published as of Bellwether's death in December 2022. Bellwether wrote all of the issue's articles, which explore a variety of sexual activities involving trans women, primarily ones who are pre-op or non-op with respect to bottom surgery. Fucking Trans Women was the first publication of note to focus on sex with trans women and was innovative in its focus on trans women's own perspectives and its inclusion of instructions for many of the sex acts depicted. Emphasizing sex acts possible with flaccid penises or not involving penises at all, it coined the term muffing to refer to stimulation of the inguinal canals, an act it popularized. The zine has received both popular-culture and scholarly attention, and was described in Sexuality & Culture as "a comprehensive guide to trans women's sexuality" and in Playboy as "widely considered" the "most in-depth guide to having sex with pre- and non-op trans femme bodies".