A solar deity or sun deity is a deity who represents the Sun or an aspect thereof. Such deities are usually associated with power and strength. Solar deities and Sun worship can be found throughout most of recorded history in various forms. The Sun is sometimes referred to by its Latin name Sol or by its Greek name Helios. The English word sun derives from Proto-Germanic *sunnǭ.

Atum, sometimes rendered as Atem, Temu, or Tem, is the primordial God in Egyptian mythology from whom all else arose. He created himself and is the father of Shu and Tefnut, the divine couple, who are the ancestors of the other Egyptian deities. Atum is also closely associated with the evening sun. As a primordial god and as the evening sun, Atum has chthonic and underworld connections. Atum was relevant to the ancient Egyptians throughout most of Egypt's history. He is believed to have been present in ideology as early as predynastic times, becoming even more prevalent during the Old Kingdom and continuing to be worshiped through the Middle and New Kingdom, though he becomes overshadowed by Re around this time.

Ptah is an ancient Egyptian deity, a creator god and patron deity of craftsmen and architects. In the triad of Memphis, he is the husband of Sekhmet and the father of Nefertem. He was also regarded as the father of the sage Imhotep.

Apep, also known as Aphoph or Apophis, is the ancient Egyptian deity who embodied darkness and disorder, and was thus the opponent of light and Maat (order/truth). Ra was the bringer of light and hence the biggest opposer of Apep.

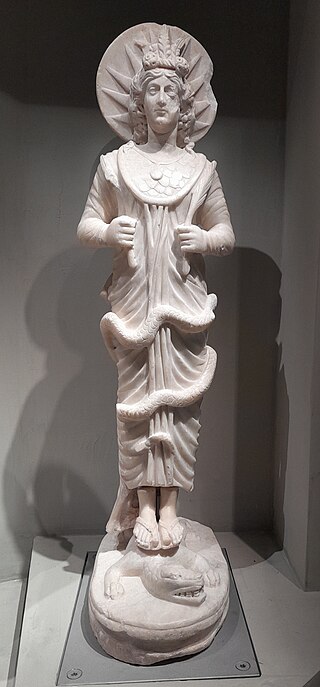

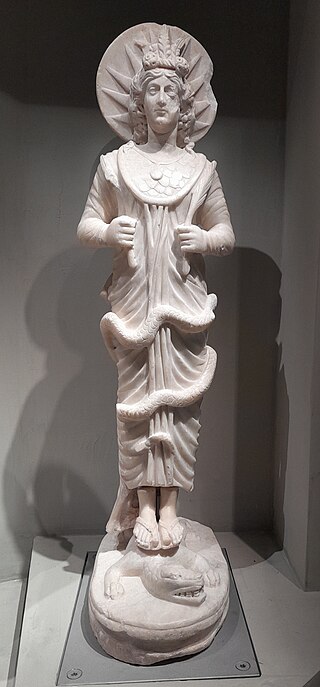

Nehebkau was the primordial snake god in ancient Egyptian mythology. Although originally considered an evil spirit, he later functions as a funerary god associated with the afterlife. As one of the forty-two assessors of Ma’at, Nehebkau was believed to judge the deceased after death and provide their souls with ka – the part of the soul that distinguished the living from the dead.

Dionysus-Osiris, alternatively Osiris-Dionysus, is a deity arising from the syncretism of the Egyptian god Osiris and the Greek god Dionysus.

The Karnak Temple Complex, commonly known as Karnak, comprises a vast mix of temples, pylons, chapels, and other buildings near Luxor, Egypt. Construction at the complex began during the reign of Senusret I in the Middle Kingdom and continued into the Ptolemaic Kingdom, although most of the extant buildings date from the New Kingdom. The area around Karnak was the ancient Egyptian Ipet-isut and the main place of worship of the 18th Dynastic Theban Triad, with the god Amun as its head. It is part of the monumental city of Thebes, and in 1979 it was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List along with the rest of the city. Karnak gets its name from the nearby, and partly surrounded, modern village of El-Karnak, 2.5 kilometres north of Luxor.

Newgrange is a prehistoric monument in County Meath in Ireland, located on a rise overlooking the River Boyne, eight kilometres west of the town of Drogheda. It is an exceptionally grand passage tomb built during the Neolithic Period, around 3200 BC, making it older than Stonehenge and the Egyptian pyramids. Newgrange is the main monument in the Brú na Bóinne complex, a World Heritage Site that also includes the passage tombs of Knowth and Dowth, as well as other henges, burial mounds and standing stones.

The religions of the ancient Near East were mostly polytheistic, with some examples of monolatry. Some scholars believe that the similarities between these religions indicate that the religions are related, a belief known as patternism.

Nabta Playa was once a large endorheic basin in the Nubian Desert, located approximately 800 kilometers south of modern-day Cairo or about 100 kilometers west of Abu Simbel in southern Egypt, 22.51° north, 30.73° east. Today the region is characterized by numerous archaeological sites. The Nabta Playa archaeological site, one of the earliest of the Egyptian Neolithic Period, is dated to circa 7500 BC.

The traditional Berber religion is the sum of ancient and native set of beliefs and deities adhered to by the Berbers. Originally, the Berbers seem to have believed in worship of the sun and moon, animism and in the afterlife, but interactions with the Phoenicians, Greeks and Romans influenced religious practice and melted traditional faiths with new ones.

The concept of Hellenistic religion as the late form of Ancient Greek religion covers any of the various systems of beliefs and practices of the people who lived under the influence of ancient Greek culture during the Hellenistic period and the Roman Empire. There was much continuity in Hellenistic religion: people continued to worship the Greek gods and to practice the same rites as in Classical Greece.

Egyptian astronomy started in prehistoric times, in the Predynastic Period. In the 5th millennium BCE, the stone circles at Nabta Playa may have made use of astronomical alignments. By the time the historical Dynastic Period began in the 3rd millennium BCE, the 365 day period of the Egyptian calendar was already in use, and the observation of stars was important in determining the annual flooding of the Nile.

Shapshu or Shapsh, and also Shamshu, was a Canaanite sun goddess. She also served as the royal messenger of the high god El, her probable father. Her most common epithets in the Ugaritic corpus are nrt ỉlm špš, rbt špš, and špš ʿlm. In the pantheon lists KTU 1.118 and 1.148, Shapshu is equated with the Akkadian dšamaš.

Amun was a major ancient Egyptian deity who appears as a member of the Hermopolitan Ogdoad. Amun was attested from the Old Kingdom together with his wife Amunet. His oracle in Siwa Oasis, located in Western Egypt near the Libyan Desert, remained the only oracle of Amun throughout. With the 11th Dynasty, Amun rose to the position of patron deity of Thebes by replacing Montu.

Ra or Re was the ancient Egyptian deity of the Sun. By the Fifth Dynasty, in the 25th and 24th centuries BC, he had become one of the most important gods in ancient Egyptian religion, identified primarily with the noon-day sun. Ra ruled in all parts of the created world: the sky, the Earth, and the underworld. He was believed to have ruled as the first pharaoh of Ancient Egypt. He was the god of the sun, order, kings and the sky.

A lunar deity or moon deity is a deity who represents the Moon, or an aspect of it. These deities can have a variety of functions and traditions depending upon the culture, but they are often related. Lunar deities and Moon worship can be found throughout most of recorded history in various forms.

*Seh₂ul and *Meh₁not are the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European Sun deity and Moon deity respectively. *Seh₂ul is reconstructed based on the solar deities of the attested Indo-European mythologies, although its gender is disputed, since there are deities of both genders. Likewise, *Meh₁not- is reconstructed based on the lunar deities of the daughter languages, but they differ in regards to their gender.