Trabzon, historically known as Trebizond, is a city on the Black Sea coast of northeastern Turkey and the capital of Trabzon Province. Trabzon became a melting pot of religions, languages and culture for centuries and a trade gateway to Persia in the southeast and the Caucasus to the northeast. The Venetian and Genoese merchants paid visits to Trabzon during the medieval period and sold silk, linen and woolen fabric. Both republics had merchant colonies within the city – Leonkastron and the former "Venetian castle" – that played a role to Trabzon similar to the one Galata played to Constantinople. Trabzon formed the basis of several states in its long history and was the capital city of the Empire of Trebizond between 1204 and 1461. During the early modern period, Trabzon, because of the importance of its port, again became a focal point of trade to Persia and the Caucasus.

The Turkish War of Independence was a series of military campaigns and a revolution waged by the Turkish National Movement, after the Ottoman Empire was occupied and partitioned following its defeat in World War I. The conflict was between the Turkish Nationalists against Allied and separatist forces over the application of Wilsonian principles, especially self-determination, in post-World War I Anatolia and eastern Thrace. The revolution concluded the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, ending the Ottoman sultanate and the Ottoman caliphate, and establishing the Republic of Turkey. This resulted in the transfer of sovereignty from the sultan-caliph to the nation, setting the stage for nationalist revolutionary reform in Republican Turkey.

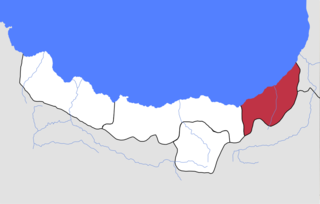

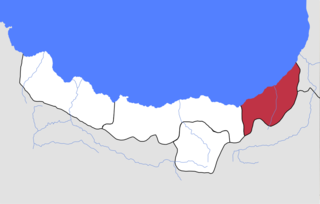

Lazistan was the Ottoman administrative name for the sanjak, under Trebizond Vilayet, comprising the Laz or Lazuri-speaking population on the southeastern shore of the Black Sea. It covered modern day land of contemporary Rize Province and the littoral of contemporary Artvin Province.

The Pontic Greeks, also Pontian Greeks or simply Pontians, are an ethnically Greek group indigenous to the region of Pontus, in northeastern Anatolia. They share a common Pontic Greek culture that is distinguished by its music, dances, cuisine, and clothing. Folk dances, such as the Serra, and traditional musical instruments, like the Pontic lyra, remain important to Pontian diaspora communities. Pontians traditionally speak Pontic Greek, a modern Greek variety, that has developed remotely in the region of Pontus. Commonly known as Pontiaka, it is traditionally called Romeika by its native speakers.

Ottoman Armenian casualties refers to the number of deaths of Ottoman Armenians between 1914 and 1923, during which the Armenian genocide occurred. Most estimates of related Armenian deaths between 1915 and 1918 range from 600,000 to 1.5 million.

Görele is a town in Giresun Province on the Black Sea coast of eastern Turkey. It is the seat of Görele District. Its population is 18,725 (2022).

The Greek genocide, which included the Pontic genocide, was the systematic killing of the Christian Ottoman Greek population of Anatolia, which was carried out mainly during World War I and its aftermath (1914–1922) – including the Turkish War of Independence (1919–1923) – on the basis of their religion and ethnicity. It was perpetrated by the government of the Ottoman Empire led by the Three Pashas and by the Government of the Grand National Assembly led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, against the indigenous Greek population of the Empire. The genocide included massacres, forced deportations involving death marches through the Syrian Desert, expulsions, summary executions, and the destruction of Eastern Orthodox cultural, historical, and religious monuments. Several hundred thousand Ottoman Greeks died during this period. Most of the refugees and survivors fled to Greece. Some, especially those in Eastern provinces, took refuge in the neighbouring Russian Empire.

Şebinkarahisar is a town in Giresun Province in the Black Sea region of northeastern Turkey. It is the administrative seat of Şebinkarahisar District. Its population is 10,695 (2022).

The Republic of Pontus was a proposed Pontic Greek state on the southern coast of the Black Sea. Its territory would have encompassed much of historical Pontus in north-eastern Asia Minor, and today forms part of Turkey's Black Sea Region. The proposed state was discussed at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, but the Greek government of Eleftherios Venizelos feared the precarious position of such a state and so it was included instead in the larger proposed state of Wilsonian Armenia. Ultimately, however, neither state came into existence and the Pontic Greek population was massacred and expelled from Turkey after 1922 and resettled in the Soviet Union or in Macedonia, Greece. This state of affairs was later formally recognized as part of the population exchange between Greece and Turkey in 1923. In modern Greek political circles, the exchange is seen as inextricable from the contemporaneous Greek genocide.

Ottoman labour battalions were a form of unfree labour in the late Ottoman Empire. The term is associated with the disarmament and murder of Ottoman Armenian soldiers during World War I, of Ottoman Greeks during the Greek genocide in the Ottoman Empire and also during the Turkish War of Independence.

The Black Sea region is a geographical region of Turkey. The largest city in the region is Samsun. Other big cities are Zonguldak, Trabzon, Ordu, Tokat, Giresun, Rize, Amasya and Sinop.

The Pontic Greek genocide, or the Pontic genocide, was the deliberate and systematic destruction of the indigenous Greek community in the Pontus region in the Ottoman Empire during World War I and its aftermath.

Genocidal rape, a form of wartime sexual violence, is the action of a group which has carried out acts of mass rape and gang rapes, against its enemy during wartime as part of a genocidal campaign. During the Armenian genocide, the Greek genocide, the Assyrian genocide, the second Sino-Japanese war, the Bangladesh Liberation War, the Bosnian War, the Rwandan genocide, the Tamil genocide, the Circassian genocide, the Congolese conflicts, the South Sudanese Civil War, the Yazidi Genocide, and Rohingya genocide, mass rapes that had been an integral part of those conflicts brought the concept of genocidal rape to international prominence. Although war rape has been a recurrent feature in conflicts throughout human history, it has usually been looked upon as a by-product of conflict and not an integral part of military policy.

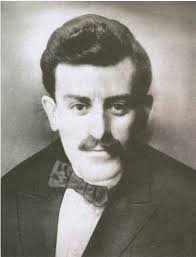

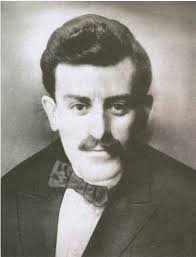

Matthaios Kofidis was an Ottoman Greek businessman, historian and a politician, who was a member of the Ottoman Parliament. He was elected in three successive periods from 1908 to 1918. In 1921 he was among the notables of the Greek community of the Pontus region who were hanged by the Turkish nationalists of Mustafa Kemal during the Pontic Greek genocide.

Nikos Kapetanidis was a Pontian Greek journalist and newspaper publisher from Rizunda. He was hanged by Turkish nationalists serving under Mustafa Kemal during the Amasya trials.

The 1921 Amasya trials were special ad hoc trials, organized by the Turkish National Movement, with the purpose to kill en masse the Greek representatives of Pontus region under a legal pretext. They occurred in Amasya, modern Turkey, during the final stage of the Pontic Greek genocide. The total number of the executed individuals is estimated to be ca. 400-450, among them 155 prominent Pontic Greeks.

Hafız Mehmet was a Turkish politician and the acting Minister of Justice for the Republic of Turkey. While serving as a deputy in Trabzon, he was a witness to the Armenian genocide. His testimony of the event is considered by genocide scholar Vahakn Dadrian as one of the "rarest corroborations of the fact of the complicity of governmental officials in the organization of the mass murder of Armenians". He was sentenced to death after the Izmir trials of 1926, charged with attempting to assassinate Mustafa Kemal Atatürk.

The Samsun deportations were a series of death marches orchestrated by the Turkish National Movement as part of its extermination of the Greek community of Samsun, a city in northern Turkey, and its environs. It was accompanied by looting, the burning of settlements, rape, and massacres. As a result, the Greek population of the city and those who had previously found refuge there—a total of c. 24,500 men, women and children—were forcibly deported from the city to the interior of Anatolia in 1921–1922. The atrocities were reported by both American Near East Relief missionaries and naval officers on destroyers that visited the region.

The Thirty-Year Genocide: Turkey's Destruction of Its Christian Minorities, 1894–1924 is a 2019 history book written by Benny Morris and Dror Ze'evi. They argue that the Armenian genocide and other contemporaneous persecution of Christians in the Ottoman Empire constitute an extermination campaign, or genocide, carried out by the Ottoman Empire against its Christian subjects.

Ali Şükrü Bey was a Turkish soldier, journalist, and politician.