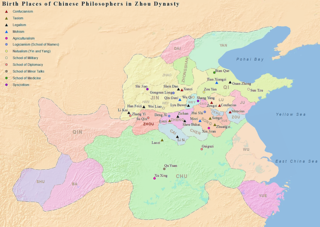

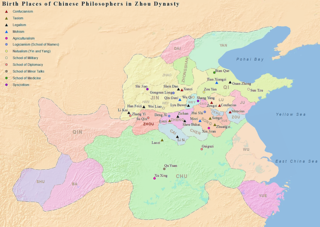

Chinese philosophy originates in the Spring and Autumn period and Warring States period, during a period known as the "Hundred Schools of Thought", which was characterized by significant intellectual and cultural developments. Although much of Chinese philosophy begun in the Warring States period, elements of Chinese philosophy have existed for several thousand years. Some can be found in the I Ching, an ancient compendium of divination, which dates back to at least 672 BCE.

The Tao Te Ching or Laozi is a Chinese classic text and foundational work of Taoism traditionally credited to the sage Laozi, though the text's authorship, date of composition and date of compilation are debated. The oldest excavated portion dates to the late 4th century BC.

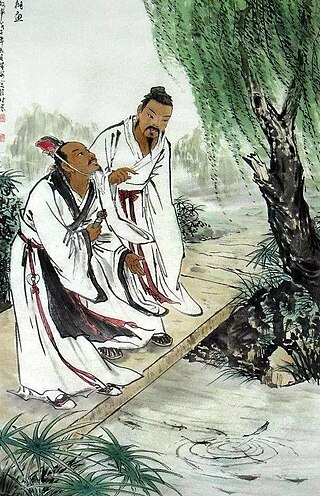

Laozi, also romanized as Lao Tzu and various other ways, was a semi-legendary ancient Chinese philosopher, author of the Tao Te Ching, the foundational text of Taoism along with the Zhuangzi. Laozi is a Chinese honorific, typically translated as "the Old Master". Modern scholarship generally regards his biographical details as invented, and his opus a collaboration. Traditional accounts say he was born as Li Er in the state of Chu in the 6th century BC during China's Spring and Autumn period, served as the royal archivist for the Zhou court at Wangcheng, met and impressed Confucius on one occasion, and composed the Tao Te Ching in a single session before retiring into the western wilderness.

Zhuang Zhou, commonly known as Zhuangzi, was an influential Chinese philosopher who lived around the 4th century BCE during the Warring States period, a period of great development in Chinese philosophy, the Hundred Schools of Thought. He is credited with writing—in part or in whole—a work known by his name, the Zhuangzi, which is one of two foundational texts of Taoism, alongside the Tao Te Ching.

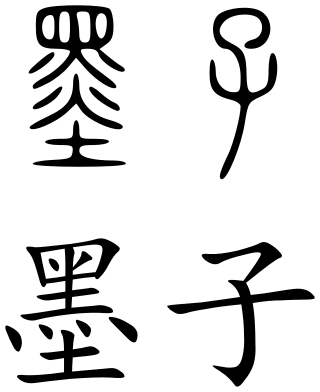

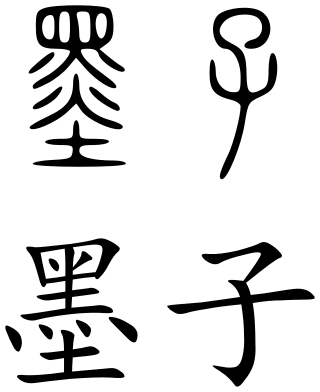

Mozi was a Chinese philosopher, logician and essayist who founded the school of Mohism during the Hundred Schools of Thought period. The ancient text Mozi contains material ascribed to him and his followers.

The School of Names, or School of Forms and Names, was a school of Chinese philosophy that grew out of Mohism during the Warring States period. Followers of the School of Names were sometimes called Logicians or Disputers. Figures associated with it include Deng Xi, Yin Wen, Hui Shi, and Gongsun Long. A contemporary of Confucius and the younger Mozi, Deng Xi, associated with litigation, is cited by Liu Xiang as the originator of the principle of xíngmíng, or ensuring that ministers' deeds (xing) harmonized with their words (ming).

Gongsun Long, courtesy name Zibing, was a Chinese philosopher, writer, and member of the School of Names, also known as the Logicians, of ancient Chinese philosophy. Gongsun ran a school and received patronage from rulers, advocating peaceful means of resolving disputes amid the martial culture of the Warring States period. His collected works comprise the Gongsun Longzi (公孫龍子) anthology. Comparatively few details are known about his life, and much of his work has been lost—only six of the fourteen essays he originally authored are still extant.

Fajia, or the School of fa (laws,methods), often translated as Legalism, is a school of mainly Warring States period classical Chinese philosophy, whose ideas contributed greatly to the formation of the bureaucratic Chinese empire, and Daoism as prominent in the early Han. The later Han takes Guan Zhong as a forefather of the Fajia. Its more Legalistic figures include ministers Li Kui and Shang Yang, and more Daoistic figures Shen Buhai and philosopher Shen Dao, with the late Han Fei drawing on both. It is often characterized in the west along realist lines. With Shang Yang, Shen Buhai and Han Fei taken as a source for Qin dynasty practices by the Han, the Qin to Tang were more characterized by its tradition.

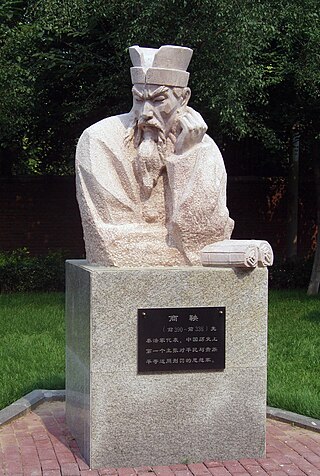

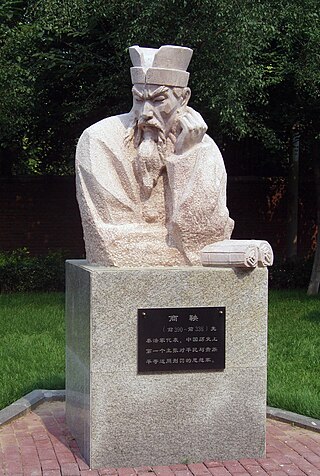

Shen Dao was a Chinese philosopher and writer. He was a Chinese Legalist theoretician most remembered for his influence on Han Fei with regards to the concept of shi, but most of his book concerns the concept of fa more commonly shared by his school. Compared with western schools, Shen Dao considered laws that are not good "still preferable to having no laws at all."

Wu wei is an ancient Chinese concept literally meaning "inexertion", "inaction", or "effortless action". Wu wei emerged in the Spring and Autumn period. With early literary examples, as an idea, in the Classic of Poetry, it becomes an important concept in the Confucian Analects, Chinese statecraft, and Daoism. It was most commonly used to refer to an ideal form of government, including the behavior of the emperor, describing a state of personal harmony, free-flowing spontaneity and laissez-faire. It generally denotes a state of spirit or state of mind, and in Confucianism, accords with conventional morality.

Hui Shi, or Huizi, was a Chinese philosopher during the Warring States period. A representative of the School of Names (Logicians), he is famous for ten paradoxes about the relativity of time and space, for instance, "I set off for Yue today and came there yesterday." Said to have written a code of laws, Hui was a prime minister in the state of Wei.

China is a special case in the history of logic, due to its relatively long isolation from the corresponding traditions that developed in Europe, India, and the Islamic world.

The Guanzi is an ancient Chinese political and philosophical text. At over 135,000 characters long, the Guanzi is one of the longest early Chinese philosophical texts. This anonymously written foundational text covers broad subject matter, notably including price regulation of commodities via the concept of "light and heavy" (轻重). Despite its later dating, it is arguably one of the most representative texts of the concepts of political economy that developed during the Spring and Autumn period.

The rectification of names is originally a doctrine of feudal Confucian designations and relationships, behaving accordingly to ensure social harmony. Without such accordance society would essentially crumble and "undertakings would not be completed." Mencius extended the doctrine to include questions of political legitimacy.

The Zhuangzi is an ancient Chinese text that is one of the two foundational texts of Taoism, alongside the Tao Te Ching. It was written during the late Warring States period (476–221 BC) and is named for its traditional author, Zhuang Zhou.

Deng Xi was a Chinese philosopher and rhetorician who was associated with the Chinese philosophical tradition School of Names. Once a senior official of the Zheng state, and a contemporary of Confucius, he is regarded as China's earliest known lawyer, with clever use of words and language in lawsuits. The Zuo Zhuan and Annals of Lü Buwei critically credit Deng with the authorship of a penal code, the earliest known statute in Chinese criminology entitled the "Bamboo Law". This was developed to take the place of the harsh, more Confucian criminal code developed by the Zheng statesman Zichan.

Huang–Lao was the most influential Chinese school of thought in the early Han dynasty, having its origins in a broader political-philosophical drive looking for solutions to strengthen the feudal order as depicted in Zhou politics. Not systematically explained by historiographer Sima Qian, it is generally interpreted as a school of Syncretism, developing into a major religion, the beginnings of religious Taoism.

Yangism was a philosophical school founded by Yang Zhu, extant during the Warring States period, that believed that human actions are and should be based on self-interest. The school has been described by sinologists as an early form of psychological and ethical egoism. The main focus of the Yangists was on the concept of xing (性), or human nature, a term later incorporated by Mencius into Confucianism. No documents directly authored by the Yangists have been discovered yet, and all that is known of the school comes from the comments of rival philosophers, specifically in the Chinese texts Huainanzi, Lüshi Chunqiu, Mengzi, and possibly the Liezi and Zhuangzi. The philosopher Mencius claimed that Yangism once rivaled Confucianism and Mohism, although the veracity of this claim remains controversial among sinologists. Because Yangism had largely faded into obscurity by the time that Sima Qian compiled his Shiji, the school was not included as one of the Hundred Schools of Thought.

Bryan W. Van Norden is an American translator of Chinese philosophical texts and scholar of Chinese and comparative philosophy. He has taught for twenty five years at Vassar College, United States, where he is currently the James Monroe Taylor Chair in Philosophy. From 2017 to 2020, he was the Kwan Im Thong Hood Cho Temple Professor at Yale-NUS College in Singapore.

In Chinese philosophy, xin refers to the "heart" and "mind". Literally, xin refers to the physical heart, though it also refers to the "mind" as the ancient Chinese believed the heart was the center of human cognition. However, emotion and reason were not considered as separate, but rather as coextensive; xin is as much cognitive as emotional, being simultaneously associated with thought and feeling. For these reasons, it is also often translated as "heart-mind". It has a connotation of intention, yet can be used to refer to long-term goals.