Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord, 1st Prince of Benevento, then Prince of Talleyrand, was a French secularized clergyman, statesman, and leading diplomat. After studying theology, he became Agent-General of the Clergy in 1780. In 1789, just before the French Revolution, he became Bishop of Autun. He worked at the highest levels of successive French governments, most commonly as foreign minister or in some other diplomatic capacity. His career spanned the regimes of Louis XVI, the years of the French Revolution, Napoleon, Louis XVIII, and Louis Philippe I. Those Talleyrand served often distrusted him but, like Napoleon, found him extremely useful. The name "Talleyrand" has become a byword for crafty and cynical diplomacy.

Louis XVIII, known as the Desired, was King of France from 1814 to 1824, except for a brief interruption during the Hundred Days in 1815. Before his reign, he spent 23 years in exile from France beginning in 1791, during the French Revolution and the First French Empire.

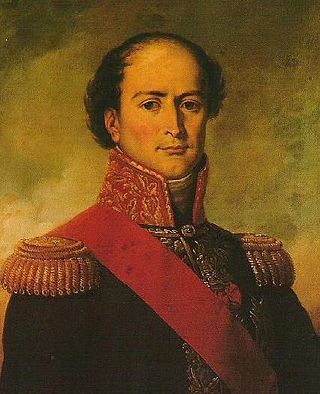

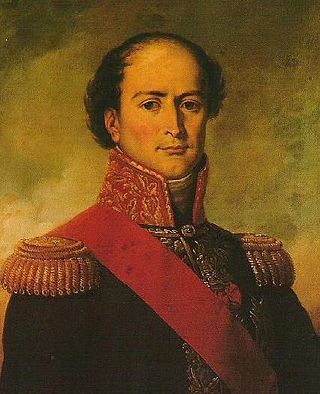

Eugène Rose de Beauharnais was a French nobleman, statesman, and military commander who served during the French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars. Through the second marriage of his mother, Joséphine de Beauharnais, he was the stepson of Napoleon Bonaparte. Under the French Empire he also became Napoleon's adopted son. He was Viceroy of the Kingdom of Italy under his stepfather, from 1805 to 1814, and commanded the Army of Italy during the Napoleonic Wars. Historians consider him one of Napoleon's most able relatives.

Louis-Nicolas d'Avout, better known as Davout, 1st Prince of Eckmühl, 1st Duke of Auerstaedt, was a French military commander and Marshal of the Empire who served during both the French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars. His talent for war, along with his reputation as a stern disciplinarian, earned him the nickname "The Iron Marshal". He is ranked along with Marshals André Masséna and Jean Lannes as one of Napoleon's finest commanders. His loyalty and obedience to Napoleon were absolute. During his lifetime, Davout's name was commonly spelled Davoust - this spelling appears on the Arc de Triomphe and in much of the correspondence between Napoleon and his generals.

Joachim Murat was a French military commander and statesman who served during the French Revolutionary Wars and Napoleonic Wars. Under the French Empire he received the military titles of Marshal of the Empire and Admiral of France. He was the first Prince Murat, Grand Duke of Berg from 1806 to 1808, and King of Naples as Joachim-Napoleon from 1808 to 1815.

Louis Antoine de Bourbon, Duke of Enghien was a member of the House of Bourbon of France. More famous for his death than his life, he was executed by order of Napoleon Bonaparte, who brought charges against him of aiding Britain and plotting against Napoleon.

Armand Emmanuel Sophie Septimanie de Vignerot du Plessis, 5th Duke of Richelieu and Fronsac, was a French statesman during the Bourbon Restoration. He was known by the courtesy title of Count of Chinon until 1788, then Duke of Fronsac until 1791, when he succeeded his father as Duke of Richelieu.

Hugues-Bernard Maret, 1st Duke of Bassano, was a French statesman, diplomat and journalist.

Louis Antoine of France, Duke of Angoulême was the elder son of Charles X and the last Dauphin of France from 1824 to 1830. He is identified by the Guinness World Records as the shortest-reigning monarch, reigning for less than 20 minutes during the July Revolution, but this is not backed up by one interpretation of the historical evidence. He never reigned over the country, but after his father's death in 1836, he was the legitimist pretender as Louis XIX.

Count Fyodor Vasilyevich Rostopchin was a Russian statesman and General of the Infantry who served as the Governor-General of Moscow during the French invasion of Russia. He was disgraced shortly after the Congress of Vienna, to which he had accompanied Tsar Alexander I. He appears as a character in Leo Tolstoy's 1869 novel War and Peace, in which he is presented very unfavorably.

Jean Baptiste Eblé was a French General, Engineer and Artilleryman during the Napoleonic Wars. He is credited with saving Napoleon's Grand Army from complete destruction in 1812.

During the French occupation of Moscow, a fire persisted from 14 to 18 September 1812 and all but destroyed the city. The Russian troops and most of the remaining civilians had abandoned the city on 14 September 1812 just ahead of French Emperor Napoleon's troops entering the city after the Battle of Borodino. The Moscow military governor, Count Fyodor Rostopchin, has often been considered responsible for organising the destruction of the sacred former capital to weaken the French army in the scorched city even more.

The Battle of Vyazma, occurred at the beginning of Napoleon's retreat from Moscow. In this encounter a Russian force commanded by General Miloradovich inflicted heavy losses on the rear guard of the Grande Armée. Although the French thwarted Miloradovich's goal of encircling and destroying the corps of Marshal Davout, they withdrew in a partial state of disorder due to ongoing Russian harassment and heavy artillery bombardments. The French reversal at Vyazma, although indecisive, was significant due to its damaging impact on several corps of Napoleon's retreating army.

The Treaty of Fontainebleau was an agreement concluded in Fontainebleau, France, on 11 April 1814 between Napoleon and representatives of Austria, Russia and Prussia. The treaty was signed in Paris on 11 April by the plenipotentiaries of both sides and ratified by Napoleon on 13 April. With this treaty, the allies ended Napoleon's rule as emperor of the French and sent him into exile on Elba.

The French invasion of Russia, also known as the Russian campaign and in Russia as the Patriotic War of 1812, was initiated by Napoleon with the aim of compelling the Russian Empire to comply with the continental blockade of the United Kingdom. Widely studied, Napoleon's incursion into Russia stands as a focal point in military history, recognized as among the most devastating military endeavors globally. In a span of fewer than six months, the campaign exacted a staggering toll, claiming the lives of nearly a million soldiers and civilians.

Auguste-Jean-Gabriel, comte de Caulaincourt was a French cavalry commander who rose to the rank of general during the First French Empire.

Michel Ordener was a French general of division and a commander in Napoleon's elite Imperial Guard. Of plebeian origins, he was born in L'Hôpital and enlisted as private at the age of 18 years in the Prince Condé's Legion. He was promoted through the ranks; as warrant officer of a regiment of Chasseurs à Cheval, he embraced the French Revolution in 1789. He advanced quickly through the officer ranks during the French Revolutionary Wars.

The French Government of the Hundred Days was formed by Napoleon I upon his resumption of the Imperial throne on 20 March 1815, replacing the government of the first Bourbon restoration which had been formed by King Louis XVIII the previous year. Following the defeat of Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo and his second abdication on 22 June 1815 the Executive Commission of 1815 was formed as a new government, declaring the Empire abolished for a second time on 26 June.

The French Provisional Government or French Executive Commission of 1815 replaced the French government of the Hundred Days that had been formed by Napoleon after his return from exile on Elba. It was formed on 22 June 1815 after the abdication of Napoleon following his defeat at the Battle of Waterloo.

The Congress of Châtillon was a peace conference held at Châtillon-sur-Seine, north-eastern France, from 5 February to 5 March 1814, in the latter stages of the War of the Sixth Coalition. Peace had previously been offered by the Coalition allies to Napoleon I's France in the November 1813 Frankfurt proposals. These proposals required that France revert to her "natural borders" of the Rhine, Pyrenees and the Alps. Napoleon was reluctant to lose his territories in Germany and Italy and refused the proposals. By December the French had been pushed back in Germany and Napoleon indicated that he would accept peace on the Frankfurt terms. The Coalition however now sought to reduce France to her 1791 borders, which would not include Belgium.