Annibale Carracci was an Italian painter and instructor, active in Bologna and later in Rome. Along with his brother and cousin, Annibale was one of the progenitors, if not founders of a leading strand of the Baroque style, borrowing from styles from both north and south of their native city, and aspiring for a return to classical monumentality, but adding a more vital dynamism. Painters working under Annibale at the gallery of the Palazzo Farnese would be highly influential in Roman painting for decades.

The Assumption of Mary is one of the four Marian dogmas of the Catholic Church. Pope Pius XII defined it on 1 November 1950 in his apostolic constitution Munificentissimus Deus as follows:

We pronounce, declare, and define it to be a divinely revealed dogma: that the Immaculate Mother of God, the ever-Virgin Mary, having completed the course of her earthly life, was assumed body and soul into heavenly glory.

The Dormition of the Mother of God is a Great Feast of the Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, and Eastern Catholic Churches. It celebrates the "falling asleep" (death) of Mary the Theotokos, and her being taken up into heaven. The Feast of the Dormition is observed on August 15, which for the churches using the Julian calendar corresponds to August 28 on the Gregorian calendar. The Armenian Apostolic Church celebrates the Dormition not on a fixed date, but on the Sunday nearest 15 August. In Western Churches the corresponding feast is known as the Assumption of Mary, with the exception of the Scottish Episcopal Church, which has traditionally celebrated the Falling Asleep of the Blessed Virgin Mary on August 15.

LudovicoCarracci was an Italian, early-Baroque painter, etcher, and printmaker born in Bologna. His works are characterized by a strong mood invoked by broad gestures and flickering light that create spiritual emotion and are credited with reinvigorating Italian art, especially fresco art, which was subsumed with formalistic Mannerism. He died in Bologna in 1619.

Domenico Zampieri, known by the diminutive Domenichino after his shortness, was an Italian Baroque painter of the Bolognese School of painters.

A doubting Thomas is a skeptic who refuses to believe without direct personal experience – a reference to the Gospel of John's depiction of the Apostle Thomas, who, in John's account, refused to believe the resurrected Jesus had appeared to the ten other apostles until he could see and feel Jesus's crucifixion wounds.

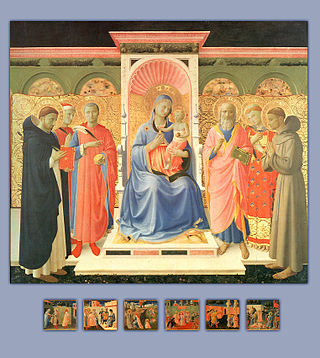

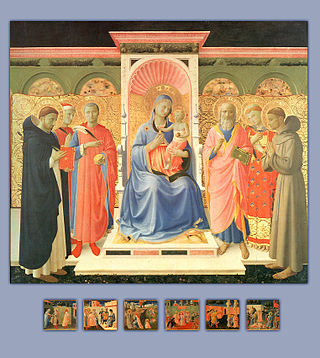

In art, a sacra conversazione, meaning "holy conversation", is a genre developed in Italian Renaissance painting, with a depiction of the Virgin and Child amidst a group of saints in a relatively informal grouping, as opposed to the more rigid and hierarchical compositions of earlier periods. Donor portraits may also be included, generally kneeling, often their patron saint is presenting them to the Virgin, and angels are frequently in attendance.

The Assumption of the Virgin Mary or Assumption of the Holy Virgin, is a painting by Peter Paul Rubens, completed in 1626 as an altarpiece for the high altar of the Cathedral of Our Lady, Antwerp, where it remains.

Giovanni Lanfranco was an Italian painter of the Baroque period.

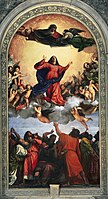

The Assumption of the Virgin is a painting by the Italian Baroque artist Annibale Carracci which was completed in 1590 and is now in the Museo del Prado in Madrid. The same subject was depicted by Carracci on the altarpiece of the famous Cerasi Chapel in Rome.

The Cerasi Chapel or Chapel of the Assumption is one of the side chapels in the left transept of the Basilica of Santa Maria del Popolo in Rome. It contains significant paintings by Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio and Annibale Carracci, two of the most important masters of Italian Baroque art, dating from 1600 to 1601.

The Death of the Virgin Mary is a common subject in Western Christian art, the equivalent of the Dormition of the Theotokos in Eastern Orthodox art. This depiction became less common as the doctrine of the Assumption gained support in the Roman Catholic Church from the Late Middle Ages onward. Although that doctrine avoids stating whether Mary was alive or dead when she was bodily taken up to Heaven, she is normally shown in art as alive. Nothing is said in the Bible about the end of Mary's life, but a tradition dating back to at least the 5th century says the twelve Apostles were miraculously assembled from their far-flung missionary activity to be present at the death, and that is the scene normally depicted, with the apostles gathered round the bed.

The Assumption of the Virgin is an oil on canvas painting by Greek artist Doménikos Theotokópoulos, known as El Greco, in 1577–1579. The painting was a central element of the altarpiece of the church of Santo Domingo el Antiguo in Toledo, Spain. It was the first of nine paintings that El Greco was commissioned to paint for this church. The Assumption of the Virgin was El Greco's first work in Toledo and started his 37-year career there. Under the influence of Michelangelo, El Greco created a painting that in essence was Italian, with a naturalistic style, monumental figures, and a Roman school palette. The composition of El Greco's depiction of the Assumption of the Virgin resembles Titian's Assumption in the Basilica dei Frari in Venice with Virgin Mary and angels above and the apostles below. On the painting Virgin Mary floats upward which symbolizes her purity, while apostles gathered around her empty tomb express amazement and concern.

Events from the year 1601 in art.

The Coronation of the Virgin or Coronation of Mary is a subject in Christian art, especially popular in Italy in the 13th to 15th centuries, but continuing in popularity until the 18th century and beyond. Christ, sometimes accompanied by God the Father and the Holy Spirit in the form of a dove, places a crown on the head of Mary as Queen of Heaven. In early versions the setting is a Heaven imagined as an earthly court, staffed by saints and angels; in later versions Heaven is more often seen as in the sky, with the figures seated on clouds. The subject is also notable as one where the whole Christian Trinity is often shown together, sometimes in unusual ways. Crowned Virgins are also seen in Eastern Orthodox Christian icons, specifically in the Russian Orthodox church after the 18th century. Mary is sometimes shown, in both Eastern and Western Christian art, being crowned by one or two angels, but this is considered a different subject.

The Girdle of Thomas, Virgin's Girdle, Holy Belt, or Sacra Cintola in modern Italian, is a Christian relic in the form of a "girdle" or knotted textile cord used as a belt, that according to a medieval legend was dropped by the Virgin Mary from the sky to Saint Thomas the Apostle at or around the time of the Assumption of Mary to Heaven. The supposed original girdle is a relic belonging to Prato Cathedral in Tuscany, Italy and its veneration has been regarded as especially helpful for pregnant women. The story was frequently depicted in the art of Florence and the whole of Tuscany, and the keeping and display of the relic at Prato generated commissions for several important artists of the early Italian Renaissance. The Prato relic has outlasted several rivals in Catholic hands, and is the Catholic equivalent of the various relics held by Eastern Christianity: the Cincture of the Theotokos of the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Holy Girdle of the Syriac Orthodox Church.

The Assumption of the Virgin by Annibale Carracci is the altarpiece of the famous Cerasi Chapel in the church of Santa Maria del Popolo in Rome. The large panel painting was created in 1600–1601. The artwork is somewhat overshadowed by the two more famous paintings of Caravaggio on the side walls of the chapel: The Conversion of Saint Paul on the Road to Damascus and The Crucifixion of Saint Peter. Both painters were important in the development of Baroque art but the contrast is striking: Carracci's Virgin glows with even light and radiates harmony, while the paintings of Caravaggio are dramatically lit and foreshortened.

Assumption of the Virgin is a fresco by Rosso Fiorentino in the Chiostro dei Voti of the Basilica della Santissima Annunziata in Florence.

The Dead Christ Mourned is an oil painting on canvas of c. 1604 by Annibale Carracci. It was in the Orleans Collection before arriving in Great Britain in 1798. In 1913 it was donated to the National Gallery, London, which describes it as "perhaps the most poignant image in [its] collection of the pietà – the lamentation over the dead Christ following his crucifixion – and one of the greatest expressions of grief in Baroque art".