The Hebrew alphabet, known variously by scholars as the Ktav Ashuri, Jewish script, square script and block script, is an abjad script used in the writing of the Hebrew language and other Jewish languages, most notably Yiddish, Ladino, Judeo-Arabic, and Judeo-Persian. In modern Hebrew, vowels are increasingly introduced. It is also used informally in Israel to write Levantine Arabic, especially among Druze. It is an offshoot of the Imperial Aramaic alphabet, which flourished during the Achaemenid Empire and which itself derives from the Phoenician alphabet.

Vocalization or vocalisation may refer to:

The mappiq is a diacritic used in the Hebrew alphabet. It is part of the Masoretes' system of niqqud, and was added to Hebrew orthography at the same time. It takes the form of a dot in the middle of a letter. An identical point with a different phonetic function is called a dagesh.

Hebrew cantillation, trope, trop, or te'amim is the manner of chanting ritual readings from the Hebrew Bible in synagogue services. The chants are written and notated in accordance with the special signs or marks printed in the Masoretic Text of the Bible, to complement the letters and vowel points.

In Hebrew orthography, niqqud or nikud is a system of diacritical signs used to represent vowels or distinguish between alternative pronunciations of letters of the Hebrew alphabet. Several such diacritical systems were developed in the Early Middle Ages. The most widespread system, and the only one still used to a significant degree today, was created by the Masoretes of Tiberias in the second half of the first millennium AD in the Land of Israel. Text written with niqqud is called ktiv menuqad.

The Tiberian vocalization, Tiberian pointing, or Tiberian niqqud is a system of diacritics (niqqud) devised by the Masoretes of Tiberias to add to the consonantal text of the Hebrew Bible to produce the Masoretic Text. The system soon became used to vocalize other Hebrew texts as well.

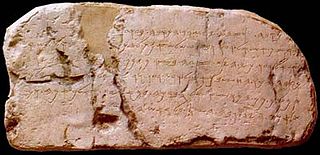

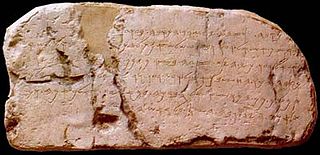

Biblical Hebrew, also called Classical Hebrew, is an archaic form of the Hebrew language, a language in the Canaanitic branch of the Semitic languages spoken by the Israelites in the area known as the Land of Israel, roughly west of the Jordan River and east of the Mediterranean Sea. The term ʿiḇrîṯ 'Hebrew' was not used for the language in the Hebrew Bible, which was referred to as שְֹפַת כְּנַעַןśəp̄aṯ kənaʿan 'language of Canaan' or יְהוּדִיתYəhûḏîṯ 'Judean', but it was used in Koine Greek and Mishnaic Hebrew texts. The Hebrew language is attested in inscriptions from about the 10th century BCE, when it was almost identical to Phoenician and other Canaanite languages, and spoken Hebrew persisted through and beyond the Second Temple period, which ended in 70 CE with the siege of Jerusalem. It eventually developed into Mishnaic Hebrew, which was spoken until the 5th century.

Tiberian Hebrew is the canonical pronunciation of the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh) committed to writing by Masoretic scholars living in the Jewish community of Tiberias in ancient Galilee c. 750–950 CE under the Abbasid Caliphate. They wrote in the form of Tiberian vocalization, which employed diacritics added to the Hebrew letters: vowel signs and consonant diacritics (nequdot) and the so-called accents. These together with the marginal notes masora magna and masora parva make up the Tiberian apparatus.

Sephardi Hebrew is the pronunciation system for Biblical Hebrew favored for liturgical use by Sephardi Jews. Its phonology was influenced by contact languages such as Spanish and Portuguese, Judaeo-Spanish (Ladino), Judeo-Arabic dialects, and Modern Greek.

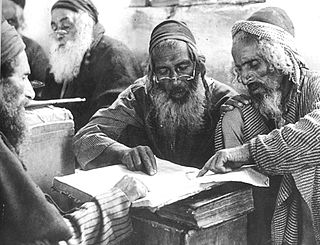

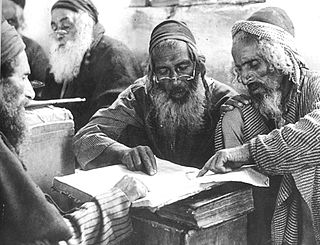

Yemenite Hebrew, also referred to as Temani Hebrew, is the pronunciation system for Hebrew traditionally used by Yemenite Jews. Yemenite Hebrew has been studied by language scholars, many of whom believe it retains older phonetic and grammatical features lost elsewhere. Yemenite speakers of Hebrew have garnered considerable praise from language purists because of their use of grammatical features from classical Hebrew.

Mizrahi Hebrew, or Eastern Hebrew, refers to any of the pronunciation systems for Biblical Hebrew used liturgically by Mizrahi Jews: Jews from Arab countries or east of them and with a background of Arabic, Persian or other languages of Asia. As such, Mizrahi Hebrew is actually a blanket term for many dialects.

The Hebrew language uses the Hebrew alphabet with optional vowel diacritics. The romanization of Hebrew is the use of the Latin alphabet to transliterate Hebrew words.

Shva or, in Biblical Hebrew, shĕwa is a Hebrew niqqud vowel sign written as two vertical dots beneath a letter. It indicates either the phoneme or the complete absence of a vowel (/Ø/).

Kamatz or qamatz is a Hebrew niqqud (vowel) sign represented by two perpendicular lines ⟨ ָ ⟩ underneath a letter. In modern Hebrew, it usually indicates the phoneme which is the "a" sound in the word spa and is transliterated as a. In these cases, its sound is identical to the sound of pataḥ in modern Hebrew. In a minority of cases it indicates the phoneme, equal to the sound of ḥolam. In traditional Ashkenazi Hebrew pronunciation, qamatz is pronounced as the phoneme, which becomes in some contexts in southern Ashkenazi dialects.

Kubutz or qubbutz and shuruk are two Hebrew niqqud vowel signs that represent the sound. In an alternative, Ashkenazi naming, the kubutz is called "shuruk" and shuruk is called "melopum".

Hebrew orthography includes three types of diacritics:

Biblical Hebrew orthography refers to the various systems which have been used to write the Biblical Hebrew language. Biblical Hebrew has been written in a number of different writing systems over time, and in those systems its spelling and punctuation have also undergone changes.

Shlomo Morag, also spelled Shelomo Morag, was an Israeli professor at the department of Hebrew Language at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Morag founded the Jewish Oral Traditions Research Center at the Hebrew University and served as the head of Ben Zvi Institute for the study of Jewish communities in the East for several years. He was a member of the Academy of the Hebrew Language and the Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, and a fellow of the American Academy of Jewish Research.

The Palestinian vocalization, Palestinian pointing, Palestinian niqqud or Vocalization of the Land of Israel is an extinct system of niqqud (diacritics) devised by scholars to add to the Hebrew Bible to indicate vowel quality. The Palestinian system is no longer used, long supplanted by the Tiberian vocalization.

Codex Babylonicus Petropolitanus, designated by Vp, is an old Masoretic manuscript of Hebrew Bible, especially the Latter Prophets, using Babylonian vocalization. This codex contains the books of Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and the Minor Prophets, with both the small and the large Masora.