Related Research Articles

Peptidoglycan or murein is a unique large macromolecule, a polysaccharide, consisting of sugars and amino acids that forms a mesh-like layer (sacculus) that surrounds the bacterial cytoplasmic membrane. The sugar component consists of alternating residues of β-(1,4) linked N-acetylglucosamine (NAG) and N-acetylmuramic acid (NAM). Attached to the N-acetylmuramic acid is an oligopeptide chain made of three to five amino acids. The peptide chain can be cross-linked to the peptide chain of another strand forming the 3D mesh-like layer. Peptidoglycan serves a structural role in the bacterial cell wall, giving structural strength, as well as counteracting the osmotic pressure of the cytoplasm. This repetitive linking results in a dense peptidoglycan layer which is critical for maintaining cell form and withstanding high osmotic pressures, and it is regularly replaced by peptidoglycan production. Peptidoglycan hydrolysis and synthesis are two processes that must occur in order for cells to grow and multiply, a technique carried out in three stages: clipping of current material, insertion of new material, and re-crosslinking of existing material to new material.

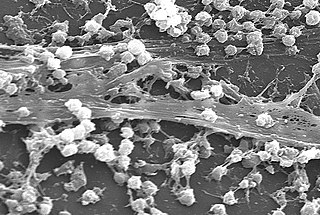

A biofilm is a syntrophic community of microorganisms in which cells stick to each other and often also to a surface. These adherent cells become embedded within a slimy extracellular matrix that is composed of extracellular polymeric substances (EPSs). The cells within the biofilm produce the EPS components, which are typically a polymeric combination of extracellular polysaccharides, proteins, lipids and DNA. Because they have a three-dimensional structure and represent a community lifestyle for microorganisms, they have been metaphorically described as "cities for microbes".

Phagocytes are cells that protect the body by ingesting harmful foreign particles, bacteria, and dead or dying cells. Their name comes from the Greek phagein, "to eat" or "devour", and "-cyte", the suffix in biology denoting "cell", from the Greek kutos, "hollow vessel". They are essential for fighting infections and for subsequent immunity. Phagocytes are important throughout the animal kingdom and are highly developed within vertebrates. One litre of human blood contains about six billion phagocytes. They were discovered in 1882 by Ilya Ilyich Mechnikov while he was studying starfish larvae. Mechnikov was awarded the 1908 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his discovery. Phagocytes occur in many species; some amoebae behave like macrophage phagocytes, which suggests that phagocytes appeared early in the evolution of life.

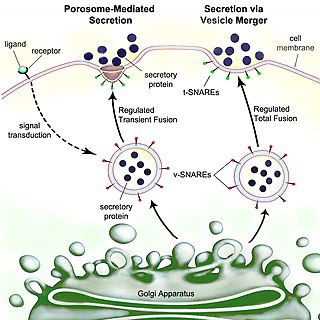

Secretion is the movement of material from one point to another, such as a secreted chemical substance from a cell or gland. In contrast, excretion is the removal of certain substances or waste products from a cell or organism. The classical mechanism of cell secretion is via secretory portals at the plasma membrane called porosomes. Porosomes are permanent cup-shaped lipoprotein structures embedded in the cell membrane, where secretory vesicles transiently dock and fuse to release intra-vesicular contents from the cell.

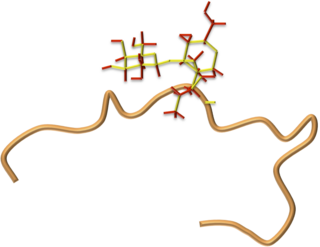

Defensins are small cysteine-rich cationic proteins across cellular life, including vertebrate and invertebrate animals, plants, and fungi. They are host defense peptides, with members displaying either direct antimicrobial activity, immune signaling activities, or both. They are variously active against bacteria, fungi and many enveloped and nonenveloped viruses. They are typically 18-45 amino acids in length, with three or four highly conserved disulphide bonds.

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), also called host defence peptides (HDPs) are part of the innate immune response found among all classes of life. Fundamental differences exist between prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells that may represent targets for antimicrobial peptides. These peptides are potent, broad spectrum antimicrobials which demonstrate potential as novel therapeutic agents. Antimicrobial peptides have been demonstrated to kill Gram negative and Gram positive bacteria, enveloped viruses, fungi and even transformed or cancerous cells. Unlike the majority of conventional antibiotics it appears that antimicrobial peptides frequently destabilize biological membranes, can form transmembrane channels, and may also have the ability to enhance immunity by functioning as immunomodulators.

The innate immune system or nonspecific immune system is one of the two main immunity strategies in vertebrates. The innate immune system is an alternate defense strategy and is the dominant immune system response found in plants, fungi, prokaryotes, and invertebrates.

A bacteriocyte, also known as a mycetocyte, is a specialized adipocyte found primarily in certain insect groups such as aphids, tsetse flies, German cockroaches, weevils. These cells contain endosymbiotic organisms such as bacteria and fungi, which provide essential amino acids and other chemicals to their host. Bacteriocytes may aggregate into a specialized organ called the bacteriome.

Paneth cells are cells in the small intestine epithelium, alongside goblet cells, enterocytes, and enteroendocrine cells. Some can also be found in the cecum and appendix. They are located below the intestinal stem cells in the intestinal glands and the large eosinophilic refractile granules that occupy most of their cytoplasm.

Virulence factors are cellular structures, molecules and regulatory systems that enable microbial pathogens to achieve the following:

Autoinducers are signaling molecules that are produced in response to changes in cell-population density. As the density of quorum sensing bacterial cells increases so does the concentration of the autoinducer. Detection of signal molecules by bacteria acts as stimulation which leads to altered gene expression once the minimal threshold is reached. Quorum sensing is a phenomenon that allows both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria to sense one another and to regulate a wide variety of physiological activities. Such activities include symbiosis, virulence, motility, antibiotic production, and biofilm formation. Autoinducers come in a number of different forms depending on the species, but the effect that they have is similar in many cases. Autoinducers allow bacteria to communicate both within and between different species. This communication alters gene expression and allows bacteria to mount coordinated responses to their environments, in a manner that is comparable to behavior and signaling in higher organisms. Not surprisingly, it has been suggested that quorum sensing may have been an important evolutionary milestone that ultimately gave rise to multicellular life forms.

Priming is the first contact that antigen-specific T helper cell precursors have with an antigen. It is essential to the T helper cells' subsequent interaction with B cells to produce antibodies. Priming of antigen-specific naive lymphocytes occurs when antigen is presented to them in immunogenic form. Subsequently, the primed cells will differentiate either into effector cells or into memory cells that can mount stronger and faster response to second and upcoming immune challenges. T and B cell priming occurs in the secondary lymphoid organs.

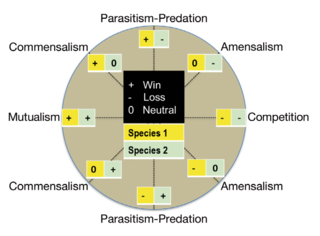

Long-term close-knit interactions between symbiotic microbes and their host can alter host immune system responses to other microorganisms, including pathogens, and are required to maintain proper homeostasis. The immune system is a host defense system consisting of anatomical physical barriers as well as physiological and cellular responses, which protect the host against harmful microorganisms while limiting host responses to harmless symbionts. Humans are home to 1013 to 1014 bacteria, roughly equivalent to the number of human cells, and while these bacteria can be pathogenic to their host most of them are mutually beneficial to both the host and bacteria.

In molecular biology, the guanylate-binding proteins family is a family of GTPases that is induced by interferon (IFN)-gamma. GTPases induced by IFN-gamma are key to the protective immunity against microbial and viral pathogens. These GTPases are classified into three groups: the small 47-KD immunity-related GTPases (IRGs), the Mx proteins, and the large 65- to 67-kd GTPases. Guanylate-binding proteins (GBP) fall into the last class.

Nasuia deltocephalinicola was reported in 2013 to have the smallest genome of all bacteria, with 112,091 nucleotides. For comparison, the human genome has 3.2 billion nucleotides. The second smallest genome, from bacteria Tremblaya princeps, has 139,000 nucleotides. While N. deltocephalinicola has the smallest number of nucleotides, it has more protein-coding genes (137) than some bacteria.

Microbial symbiosis in marine animals was not discovered until 1981. In the time following, symbiotic relationships between marine invertebrates and chemoautotrophic bacteria have been found in a variety of ecosystems, ranging from shallow coastal waters to deep-sea hydrothermal vents. Symbiosis is a way for marine organisms to find creative ways to survive in a very dynamic environment. They are different in relation to how dependent the organisms are on each other or how they are associated. It is also considered a selective force behind evolution in some scientific aspects. The symbiotic relationships of organisms has the ability to change behavior, morphology and metabolic pathways. With increased recognition and research, new terminology also arises, such as holobiont, which the relationship between a host and its symbionts as one grouping. Many scientists will look at the hologenome, which is the combined genetic information of the host and its symbionts. These terms are more commonly used to describe microbial symbionts.

A symbiosome is a specialised compartment in a host cell that houses an endosymbiont in a symbiotic relationship.

Drosocin is a 19-residue long antimicrobial peptide (AMP) of flies first isolated in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, and later shown to be conserved throughout the genus Drosophila. Drosocin is regulated by the NF-κB Imd signalling pathway in the fly.

The Imd pathway is a broadly-conserved NF-κB immune signalling pathway of insects and some arthropods that regulates a potent antibacterial defence response. The pathway is named after the discovery of a mutation causing severe immune deficiency. The Imd pathway was first discovered in 1995 using Drosophila fruit flies by Bruno Lemaitre and colleagues, who also later discovered that the Drosophila Toll gene regulated defence against Gram-positive bacteria and fungi. Together the Toll and Imd pathways have formed a paradigm of insect immune signalling; as of September 2, 2019, these two landmark discovery papers have been cited collectively over 5000 times since publication on Google Scholar.

The Morganellaceae are a family of Gram-negative bacteria that include some important human pathogens formerly classified as Enterobacteriaceae. This family is a member of the order Enterobacterales in the class Gammaproteobacteria of the phylum Pseudomonadota. Genera in this family include the type genus Morganella, along with Arsenophonus, Cosenzaea, Moellerella, Photorhabdus, Proteus, Providencia and Xenorhabdus.

References

- ↑ Masson, Florent; Zaidman-Rémy, Anna; Heddi, Abdelaziz (26 May 2016). "Antimicrobial peptides and cell processes tracking endosymbiont dynamics". Philosophical Transactions: Biological Sciences. 371 (1695): 1–9. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0298. JSTOR 24768785. PMC 4874395 . PMID 27160600.

- ↑ Jensen, Mari N. (9 June 2006). "Three-Way Symbiosis Supplies Insect Pest With Well-Rounded Diet". Phys.org.

- ↑ Normark, Benjamin B. (2004). "The Strange Case of the Armored Scale Insect and Its Bacteriome". PLOS Biology. 2 (3): e43. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020043 . PMC 368156 . PMID 15024412.