The Nez Perce are an Indigenous people of the Plateau who still live on a fraction of the lands on the southeastern Columbia River Plateau in the Pacific Northwest. This region has been occupied for at least 11,500 years.

Twin Bridges is a town in Madison County, Montana, United States. It lies at the confluence of the Ruby, Beaverhead and Big Hole rivers which form the Jefferson River. Twin Bridges is a well-known fly fishing mecca for trout anglers. The population was 330 at the 2020 census.

The Madison River is a headwater tributary of the Missouri River, approximately 183 miles (295 km) long, in Wyoming and Montana. Its confluence with the Jefferson and Gallatin rivers near Three Forks, Montana forms the Missouri River.

The Ruby River is a tributary of the Beaverhead River, approximately 76 mi (122 km) long, in southwestern Montana in the United States. It rises in the Beaverhead National Forest in southwestern Madison County between the Snowcrest Range and the Gravelly Range. It flows north through the Ruby River Reservoir, past Alder, then northwest, flowing between the Tobacco Root Mountains to the northeast and the Ruby Range to the southwest. It joins the Beaverhead near Twin Bridges. The Beaverhead becomes the Jefferson River 2 mi (3.2 km) downstream where it joins the Big Hole River.

The East Gallatin River flows 42 miles (68 km) in a northwesterly direction through the Gallatin valley, Gallatin County, Montana. Rising from the confluence of Rocky Creek and several other small streams, the East Gallatin begins about one mile (1.6 km) east of downtown Bozeman, Montana. The river joins the main stem of the Gallatin River 2.3 miles (3.7 km) north of Manhattan, Montana. Throughout its course, the river traverses mostly valley floor ranch and farm land with typical summer flows of approximately 50 cu ft/s (1.4 m3/s).

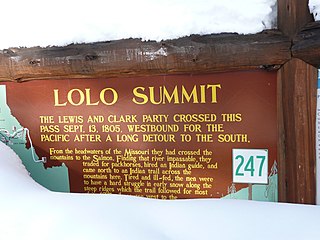

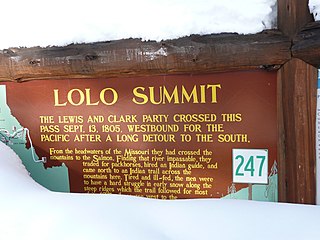

Lolo Pass, elevation 5,233 feet (1,595 m), is a mountain pass in the western United States, in the Bitterroot Range of the northern Rocky Mountains. It is on the border between the states of Montana and Idaho, approximately forty miles (65 km) west-southwest of Missoula, Montana.

The Nez Perce National Historical Park is a United States National Historical Park comprising 38 sites located across the states of Idaho, Montana, Oregon, and Washington, which include traditional aboriginal lands of the Nez Perce people. The sites are strongly associated with the resistance of Chief Joseph and his band, who in June 1877 migrated from Oregon in an attempt to reach freedom in Canada and avoid being forced on to a reservation. They were pursued by U.S. Army cavalry forces and fought numerous skirmishes against them during the so-called Nez Perce War, which eventually ended with Chief Joseph's surrender in the Montana Territory.

The Arctic grayling is a species of freshwater fish in the salmon family Salmonidae. T. arcticus is widespread throughout the Arctic and Pacific drainages in Canada, Alaska, and Siberia, as well as the upper Missouri River drainage in Montana. In the U.S. state of Arizona, an introduced population is found in the Lee Valley and other lakes in the White Mountains. They were also stocked at Toppings Lake by the Teton Range and in lakes in the high Uinta Mountains in Utah, as well as alpine lakes of the Boulder Mountains (Idaho) in central Idaho.

The Battle of the Big Hole was fought in Montana Territory, August 9–10, 1877, between the United States Army and the Nez Perce tribe of Native Americans during the Nez Perce War. Both sides suffered heavy casualties. The Nez Perce withdrew in good order from the battlefield and continued their long fighting retreat that would result in their attempt to reach Canada and asylum.

Big Hole National Battlefield preserves a battlefield in the western United States, located in Beaverhead County, Montana. In 1877, the Nez Perce fought a delaying action against the U.S. Army's 7th Infantry Regiment here on August 9 and 10, during their failed attempt to escape to Canada. This action, the Battle of the Big Hole, was the largest battle fought between the Nez Perce and U.S. Government forces in the five-month conflict known as the Nez Perce War.

The Beaverhead–Deerlodge National Forest is the largest of the National Forests in Montana, United States. Covering 3.36 million acres (13,600 km2), the forest is broken into nine separate sections and stretches across eight counties in the southwestern area of the state. President Theodore Roosevelt named the two forests in 1908 and they were merged in 1996. Forest headquarters are located in Dillon, Montana. In Roosevelt's original legislation, the Deerlodge National Forest was called the Big Hole Forest Reserve. He created this reserve because the Anaconda Copper Mining Company, based in Butte, Montana, had begun to clearcut the upper Big Hole River watershed. The subsequent erosion, exacerbated by smoke pollution from the Anaconda smelter, was devastating the region. Ranchers and conservationists alike complained to Roosevelt, who made several trips to the area. (Munday 2001)

The Firehole River is located in northwestern Wyoming, and is one of the two major tributaries of the Madison River. It flows north approximately 21 miles (34 km) from its source in Madison Lake on the Continental Divide to join the Gibbon River at Madison Junction in Yellowstone National Park. It is part of the Missouri River system.

The Manistee River is a 190-mile-long (310 km) river in the Lower Peninsula of the U.S. state of Michigan. The river rises in the Northern Lower Peninsula, and flows in a generally southwesterly direction to its mouth at Lake Michigan at the eponymous city of Manistee.

Pat Munday is an American environmentalist, writer, and college professor living in Butte, Montana. He was awarded the Liebig-Woehler Freundschaft Prize for scholarship in the history of chemistry, and contributions through environmental activism.

The Gibbon River flows east of the Continental Divide in Yellowstone National Park, in northwestern Wyoming, the Northwestern United States. Along with the Firehole River, it is a major tributary of the Madison River, which itself is a tributary of the Missouri River.

Angling in Yellowstone National Park is a major reason many visitors come to the park each year and since it was created in 1872, the park has drawn anglers from around the world to fish its waters. In 2006, over 50,000 park fishing permits were issued to visitors. The park contains hundreds of miles of accessible, high-quality trout rivers containing wild trout populations—over 200 creeks, streams and rivers are fishable. There are 45 fishable lakes and several large lakes are easily accessible to visitors. Additionally, the park's remote sections provide anglers ample opportunity to visit rivers, streams, creeks and lakes that receive little angling pressure. With the exception of one specially designated drainage, all the park's waters are restricted to artificial lures and fly fishing. The Madison, Firehole and a section of the Gibbon rivers are restricted to fly fishing only.

Grebe Lake is a 156 acres (0.63 km2) backcountry lake in Yellowstone National Park most noted for its population of Arctic grayling. Grebe Lake comprises the headwaters of the Gibbon River. Grebe Lake is located approximately 3.1 miles (5.0 km) north of the Norris-Canyon section of the Grand Loop Road. The trail to the lake passes through mostly level Lodgepole Pine forest and open meadows. The lake was named by J.P. Iddings, a geologist with the Arnold Hague geologic surveys. There are four backcountry campsites located on the lake.

A beaverslide is a device for stacking hay, made of wooden poles and planks, that builds haystacks of loose, unbaled hay to be stored outdoors and used as fodder for livestock. The beaverslide consists of a frame supporting an inclined plane up which a load of hay is pushed to a height of about 30 feet (9 m), before dropping through a large gap. The resulting loaf-shaped haystacks can be up to 30 feet high, can weigh up to 20 tons, and can theoretically last up to five or six years. It was invented in the early 1900s and was first called the Beaverhead County Slide Stacker after its place of origin, the Big Hole Valley in Beaverhead County, Montana. The name was quickly shortened to "beaverslide."

The Montana Arctic grayling is a North American freshwater fish in the salmon family Salmonidae. The Montana Arctic grayling, native to the upper Missouri River basin in Montana and Wyoming, is a disjunct population or subspecies of the more widespread Arctic grayling. It occurs in fluvial and adfluvial, lacustrine forms. The Montana grayling is a species of special concern in Montana and had candidate status for listing under the national Endangered Species Act. It underwent a comprehensive status review by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which in 2014 decided not to list it as threatened or endangered. Current surviving native populations in the Big Hole River and Red Rock River drainages represent approximately four percent of the subspecies' historical range.