Thomas Cowperthwait Eakins was an American realist painter, photographer, sculptor, and fine arts educator. He is widely acknowledged to be one of the most important American artists.

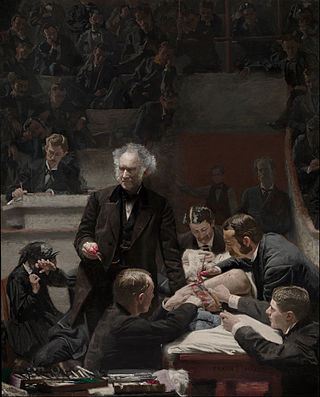

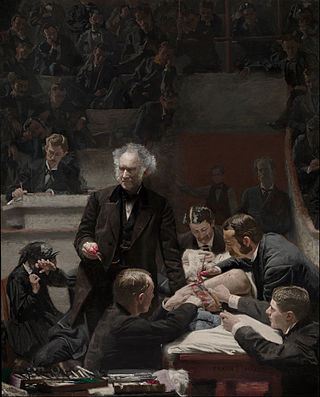

The Gross Clinic or The Clinic of Dr. Gross is an 1875 painting by American artist Thomas Eakins. It is oil on canvas and measures 8 feet (240 cm) by 6.5 feet (200 cm).

Samuel David Gross was an American academic trauma surgeon. Surgeon biographer Isaac Minis Hays called Gross "The Nestor of American Surgery." He is immortalized in Thomas Eakins' The Gross Clinic (1875), a prominent American painting of the nineteenth century. A bronze statue of him was cast by Alexander Stirling Calder and erected on the National Mall, but moved in 1970 to Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia.

The conservation-restoration of the frescoes of the Sistine Chapel was one of the most significant conservation-restorations of the 20th century.

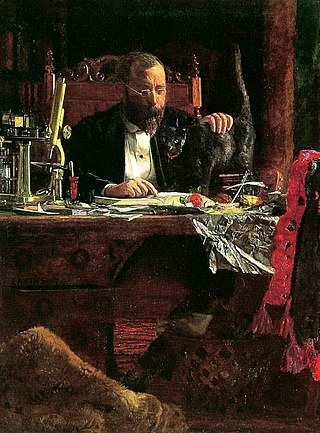

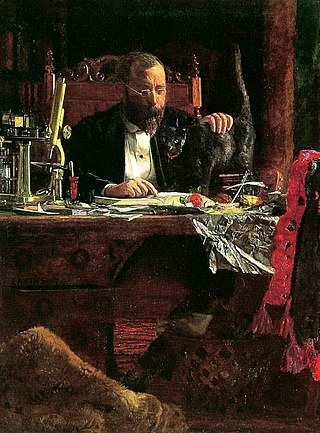

The Portrait of Professor Benjamin H. Rand is an 1874 painting by Thomas Eakins. It is an oil on canvas that depicts Benjamin H. Rand, a doctor at Jefferson Medical College who taught Eakins anatomy. It is held at the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, in Bentonville, Arkansas.

Inpainting is a conservation process where damaged, deteriorated, or missing parts of an artwork are filled in to present a complete image. This process is commonly used in image restoration. It can be applied to both physical and digital art mediums such as oil or acrylic paintings, chemical photographic prints, sculptures, or digital images and video.

The Swimming Hole is an 1884–85 painting by the American artist Thomas Eakins (1844–1916), Goodrich catalog #190, in the collection of the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth, Texas. Executed in oil on canvas, it depicts six men swimming naked in a lake, and is considered a masterpiece of American painting. According to art historian Doreen Bolger it is "perhaps Eakins' most accomplished rendition of the nude figure", and has been called "the most finely designed of all his outdoor pictures". Since the Renaissance, the human body has been considered both the basis of artists' training and the most challenging subject to depict in art, and the nude was the centerpiece of Eakins' teaching program at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. For Eakins, this picture was an opportunity to display his mastery of the human form.

The Agnew Clinic is an 1889 oil painting by American artist Thomas Eakins. It was commissioned to honor anatomist and surgeon David Hayes Agnew, on his retirement from teaching at the University of Pennsylvania.

Wrestlers is a name shared by three closely related 1899 paintings by American artist Thomas Eakins,. The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) owns the finished painting (G-317), and the oil sketch (G-318). The Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA) owns a slightly smaller unfinished version (G-319). All three works depict a pair of nearly naked men engaged in a wrestling match. The setting for the finished painting is the Quaker City Barge Club (defunct), which once stood on Philadelphia's Boathouse Row.

The Fairman Rogers Four-in-Hand is an 1879-80 painting by Thomas Eakins. It shows Fairman Rogers driving a coaching party in his four-in-hand carriage through Philadelphia's Fairmount Park. It is thought to be the first painting to examine precisely, through systematic photographic analysis, how horses move.

Samuel Gross (1897) is a bronze statue by sculptor Alexander Stirling Calder that was created as a monument to the American surgeon Dr. Samuel D. Gross (1805–1884). It was commissioned for and originally installed at the Army Medical School in Washington, D.C., on what is now the National Mall.

A paintings conservator is an individual responsible for protecting cultural heritage in the form of painted works of art. These individuals are most often under the employ of museums, conservation centers, or other cultural institutions. They oversee the physical care of collections, and are trained in chemistry and practical application of techniques for repairing and restoring paintings.

The conservation and restoration of musical instruments is performed by conservator-restorers who are professionals, properly trained to preserve or protect historical and current musical instruments from past or future damage or deterioration. Because musical instruments can be made entirely of, or simply contain, a wide variety of materials such as plastics, woods, metals, silks, and skin, to name a few, a conservator should be well-trained in how to properly examine the many types of construction materials used in order to provide the highest level or preventive and restorative conservation.

The conservation and restoration of wooden furniture is an activity dedicated to the preservation and protection of wooden furniture objects of historical and personal value. When applied to cultural heritage this activity is generally undertaken by a conservator-restorer. Furniture conservation and restoration can be divided into two general areas: structure and finish. Structure generally relates to wood and can be divided into solid, joined, and veneered wood. The finish of furniture can be painted or transparent.

The conservation and restoration of painting frames is the process through which picture frames are preserved. Frame conservation and restoration includes general cleaning of the frame, as well as in depth processes such as replacing damaged ornamentation, gilding, and toning.

The conservation and restoration of paintings is carried out by professional painting conservators. Paintings cover a wide range of various mediums, materials, and their supports. Painting types include fine art to decorative and functional objects spanning from acrylics, frescoes, and oil paint on various surfaces, egg tempera on panels and canvas, lacquer painting, water color and more. Knowing the materials of any given painting and its support allows for the proper restoration and conservation practices. All components of a painting will react to its environment differently, and impact the artwork as a whole. These material components along with collections care will determine the longevity of a painting. The first steps to conservation and restoration is preventive conservation followed by active restoration with the artist's intent in mind.

The conservation and restoration of ancient Greek pottery is a sub-section of the broader topic of conservation and restoration of ceramic objects. Ancient Greek pottery is one of the most commonly found types of artifacts from the ancient Greek world. The information learned from vase paintings forms the foundation of modern knowledge of ancient Greek art and culture. Most ancient Greek pottery is terracotta, a type of earthenware ceramic, dating from the 11th century BCE through the 1st century CE. The objects are usually excavated from archaeological sites in broken pieces, or shards, and then reassembled. Some have been discovered intact in tombs. Professional conservator-restorers, often in collaboration with curators and conservation scientists, undertake the conservation-restoration of ancient Greek pottery.

The conservation-restoration of panel paintings involves preventive and treatment measures taken by paintings conservators to slow deterioration, preserve, and repair damage. Panel paintings consist of a wood support, a ground, and an image layer. They are typically constructed of two or more panels joined together by crossbeam braces which can separate due to age and material instability caused by fluctuations in relative humidity and temperature. These factors compromise structural integrity and can lead to warping and paint flaking. Because wood is particularly susceptible to pest damage, an IPM plan and regulation of the conditions in storage and display are essential. Past treatments that have fallen out of favor because they can cause permanent damage include transfer of the painting onto a new support, planing, and heavy cradling. Today's conservators often have to remediate damage from previous restoration efforts. Modern conservation-restoration techniques favor minimal intervention that accommodates wood's natural tendency to react to environmental changes. Treatments may include applying flexible battens to minimize deformation or simply leaving distortions alone, instead focusing on preventive care to preserve the artwork in its original state.

The Progress of Medicine in the Philippines is a painting by Filipino artist Botong Francisco. It was commissioned in 1953 to depict the history of Philippine medicine. It is currently on display in the National Museum of Fine Arts in Manila.