The Court of Cassation is one of the four courts of last resort in France. It has jurisdiction over all civil and criminal matters triable in the judicial system; it is the supreme court of appeal in these cases. It has jurisdiction to review the law, as well as to certify questions of law, to determine miscarriages of justice. The Court is located in the Palace of Justice in the 1st arrondissement of Paris.

In France, career judges are considered civil servants exercising one of the sovereign powers of the state, so French citizens are eligible for judgeship, but not citizens of the other EU countries. France's independent court system enjoys special statutory protection from the executive branch. Procedures for the appointment, promotion, and removal of judges vary depending on whether it is for the ordinary or administrative stream. Judicial appointments in the judicial stream must be approved by a special panel, the High Council of the Judiciary. Once appointed, career judges serve for life and cannot be removed without specific disciplinary proceedings conducted before the council with due process.

The judicial system of Israel consists of secular courts and religious courts. The law courts constitute a separate and independent unit of Israel's Ministry of Justice. The system is headed by the President of the Supreme Court and the Minister of Justice.

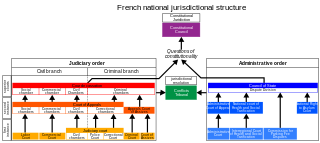

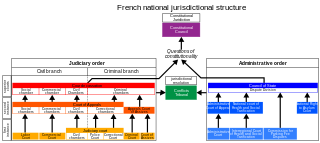

French law has a dual jurisdictional system comprising private law, also known as judicial law), and public law.

In France, a cour d'assises, or Court of Assizes or Assize Court, is a criminal trial court with original and appellate limited jurisdiction to hear cases involving defendants accused of felonies, meaning crimes as defined in French law. It is the only French court consisting in a jury trial.

In France, the Tribunal d'instance is a judicial lower court of record of first instance for general civil suits and includes a criminal division, the Police Court, which hears cases of misdemeanors or summary offences (contraventions). Since it has original jurisdiction, the Court's rulings may be appealed to a French appellate court or Supreme Court. The court was formerly known as a Justice of the Peace Court until the judicial restructuring of 1958.

The tribunals of first instance are the main trial courts in the judicial system of Belgium. The tribunals of first instance are courts of general jurisdiction; in the sense that they have original jurisdiction over all types of cases not explicitly attributed to other courts. They handle a wide range of civil cases, criminal cases, and cases under the scope of juvenile law and family law. They also hear appeals against the judgements of the police tribunals and justices of the peace. The judgements of the tribunals of first instance can be appealed to the courts of appeal in turn. There is a tribunal of first instance for each of the twelve judicial arrondissements ("districts") of Belgium, except for the arrondissement of Brussels. The arrondissement of Brussels has two tribunals of first instance, a Dutch-speaking one and a French-speaking one, due to the sensitive linguistical situation in the area. The territories of the current judicial arrondissements largely coincide with those of the provinces of Belgium. Most of the tribunals of first instance have multiple geographical divisions, with each having their own seat. As of 2020, the 13 tribunals of first instance have 27 seats in total. Further below, an overview is provided of all seats of the tribunals of first instance per arrondissement.

The police tribunal is the traffic court and trial court which tries minor contraventions in the judicial system of Belgium. It is the lowest Belgian court with criminal jurisdiction. There is a police tribunal for each judicial arrondissement ("district"), except for Brussels-Halle-Vilvoorde, where there are multiple police tribunals due to the area's sensitive linguistic situation. Most of them hear cases in multiple seats per arrondissement. As of 2018, there are 15 police tribunals in total, who hear cases in 38 seats. Further below, an overview is provided of all seats of the police tribunal per judicial arrondissement.

The courts of appeal are the main appellate courts in the judicial system of Belgium, which hear appeals against judgements of the tribunals of first instance, the enterprise tribunals and the presidents of those tribunals in their judicial area. There are five courts of appeal for each of the five judicial areas, which are the largest geographical subdivisions of Belgium for judicial purposes. The division of the Belgian territory into the five judicial areas is laid down in article 156 of the Belgian Constitution. A judicial area covers multiple judicial arrondissements ("districts"), except for the judicial area of Mons. Each arrondissement has a tribunal of first instance. Further below, an overview is provided of the five courts of appeal and the judicial arrondissements their judicial area covers. It is important to note that the courts of appeal do not hear appeals against judgements of the labour tribunals; these are heard by the courts of labour.

The current judiciary of Niger was established with the creation of the Fourth Republic in 1999. The constitution of December 1992 was revised by national referendum on 12 May 1996 and, again, by referendum, revised to the current version on 18 July 1999. It is an inquisitorial system based on the Napoleonic Code, established in Niger during French colonial rule and the 1960 constitution of Niger. The Court of Appeals reviews questions of fact and law, while the Supreme Court reviews application of the law and constitutional questions. The High Court of Justice (HCJ) deals with cases involving senior government officials. The justice system also includes civil criminal courts, customary courts, traditional mediation, and a military court. The military court provides the same rights as civil criminal courts; however, customary courts do not. The military court cannot try civilians.

The judiciary of the Republic of Chile includes one Supreme Court, one Constitutional Court, 16 Courts of Appeal, 84 Oral Criminal Tribunals and Guarantee Judges; 7 Military Tribunals; over 300 Local Police Courts; and many other specialized Tribunals and courts in matter of family, labor, customs, taxes, electoral affairs, etc.

The judiciary of Belgium is similar to the French judiciary. Belgium evolved from a unitary to a federal state, but its judicial system has not been adapted to a federal system.

In France, a cour d’appel of the ordre judiciaire (judiciary) is a juridiction de droit commun du second degré, a. It examines judgements, for example from the correctional tribunal or a tribunal de grande instance. When one of the parties is not satisfied with the verdict, it can appeal. While communications from jurisdictions of first instance are termed "judgements", or judgments, a court of appeal renders an arrêt (verdict), which may either uphold or annul the initial judgment. A verdict of the court of appeal may be further appealed en cassation. If the appeal is admissible at the cour de cassation, that court does not re-judge the facts of the matter a third time, but may investigate and verify whether the rules of law were properly applied by the lower courts.

A police tribunal is a criminal jurisdiction which judges all classes of contraventions committed by adults. More serious offenses (infractions) are judged by a tribunal correctionnel, correctional tribunal, when they are délits or misdemeanors, or by a cour d'assises.

In France, the tribunal correctionnel is the court of first instance that governs in penal matters over offenses classified as misdemeanors and committed by an adult. In 2013, French correctional tribunals rendered 576,859 judgments on action publique, pronounced 501,171 verdicts and homologué 67,983 compositions pénales.

In France the jurisdictions of the ordre judiciaire, of the French court system are empowered to try either litigation between persons or criminal law cases. They may intervene:

The judicial system of Ivory Coast was greatly influenced by its time as a French colony. The system has two levels. The lower courts include courts of appeals, courts of first instance, courts of assize, and the justice of the peace courts. The upper level includes the Supreme Court, the High Court of Justice, and the State Security Court. The remainder of the professional judiciary exists in the Central Administration of the Ministry of Justice. All members of the professional judiciary must hold a bachelor of law degree and can not hold an elected office while a member.

Criminal law in France is one of the branches of the juridical system of the French Republic. The field of criminal law is defined as a sector of French law, and is a combination of public and private law, insofar as it punishes private behavior on behalf of society as a whole. Its function is to define, categorize, prevent, and punish criminal offenses committed by a person, whether a natural person or a juridical person. In this sense it is of a punitive nature, as opposed to civil law in France, which settles disputes between individuals, or administrative law which deals with issues between individuals and government.

This glossary of French criminal law is a list of explanations or translations of contemporary and historical concepts of criminal law in France.

In French law, the investigation phase in a criminal proceeding is the procedure during which an investigating judge gathers evidence on the commission of an offense and decides whether to refer the persons charged to the trial court.