Related Research Articles

In physics, a state of matter is one of the distinct forms in which matter can exist. Four states of matter are observable in everyday life: solid, liquid, gas, and plasma. Many intermediate states are known to exist, such as liquid crystal, and some states only exist under extreme conditions, such as Bose–Einstein condensates and Fermionic condensates, neutron-degenerate matter, and quark–gluon plasma. For a complete list of all exotic states of matter, see the list of states of matter.

An electron and a electron hole that are attracted to each other by the Coulomb force can form a bound state called an exciton. It is an electrically neutral quasiparticle that exists mainly in condensed matter, including insulators, semiconductors, some metals, but also in certain atoms, molecules and liquids. The exciton is regarded as an elementary excitation that can transport energy without transporting net electric charge.

The elementary charge, usually denoted by e, is a fundamental physical constant, defined as the electric charge carried by a single proton or, equivalently, the magnitude of the negative electric charge carried by a single electron, which has charge −1 e.

Fermi liquid theory is a theoretical model of interacting fermions that describes the normal state of most metals at sufficiently low temperatures. The interactions among the particles of the many-body system do not need to be small. The phenomenological theory of Fermi liquids was introduced by the Soviet physicist Lev Davidovich Landau in 1956, and later developed by Alexei Abrikosov and Isaak Khalatnikov using diagrammatic perturbation theory. The theory explains why some of the properties of an interacting fermion system are very similar to those of the ideal Fermi gas, and why other properties differ.

A surface acoustic wave (SAW) is an acoustic wave traveling along the surface of a material exhibiting elasticity, with an amplitude that typically decays exponentially with depth into the material, such that they are confined to a depth of about one wavelength.

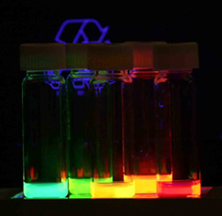

Quantum dots (QDs), also called semiconductor nanocrystals, are semiconductor particles a few nanometres in size, having optical and electronic properties that differ from those of larger particles as a result of quantum mechanical effects. They are a central topic in nanotechnology and materials science. When the quantum dots are illuminated by UV light, an electron in the quantum dot can be excited to a state of higher energy. In the case of a semiconducting quantum dot, this process corresponds to the transition of an electron from the valence band to the conductance band. The excited electron can drop back into the valence band releasing its energy as light. This light emission (photoluminescence) is illustrated in the figure on the right. The color of that light depends on the energy difference between the conductance band and the valence band, or the transition between discrete energy states when the band structure is no longer well-defined in QDs.

In condensed matter physics, a quasiparticle is a concept used to describe a collective behavior of a group of particles that can be treated as if they were a single particle. Formally, quasiparticles and collective excitations are closely related phenomena that arise when a microscopically complicated system such as a solid behaves as if it contained different weakly interacting particles in vacuum.

A Luttinger liquid, or Tomonaga–Luttinger liquid, is a theoretical model describing interacting electrons in a one-dimensional conductor. Such a model is necessary as the commonly used Fermi liquid model breaks down for one dimension.

The fractional quantum Hall effect (FQHE) is a physical phenomenon in which the Hall conductance of 2-dimensional (2D) electrons shows precisely quantized plateaus at fractional values of , where e is the electron charge and h is the Planck constant. It is a property of a collective state in which electrons bind magnetic flux lines to make new quasiparticles, and excitations have a fractional elementary charge and possibly also fractional statistics. The 1998 Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to Robert Laughlin, Horst Störmer, and Daniel Tsui "for their discovery of a new form of quantum fluid with fractionally charged excitations" The microscopic origin of the FQHE is a major research topic in condensed matter physics.

A two-dimensional electron gas (2DEG) is a scientific model in solid-state physics. It is an electron gas that is free to move in two dimensions, but tightly confined in the third. This tight confinement leads to quantized energy levels for motion in the third direction, which can then be ignored for most problems. Thus the electrons appear to be a 2D sheet embedded in a 3D world. The analogous construct of holes is called a two-dimensional hole gas (2DHG), and such systems have many useful and interesting properties.

In condensed matter physics, spin–charge separation is an unusual behavior of electrons in some materials in which they 'split' into three independent particles, the spinon, the orbiton and the holon. The electron can always be theoretically considered as a bound state of the three, with the spinon carrying the spin of the electron, the orbiton carrying the orbital degree of freedom and the chargon carrying the charge, but in certain conditions they can behave as independent quasiparticles.

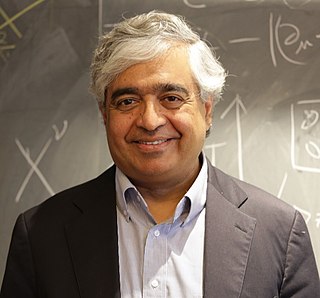

Subir Sachdev is Herchel Smith Professor of Physics at Harvard University specializing in condensed matter. He was elected to the U.S. National Academy of Sciences in 2014, and received the Lars Onsager Prize from the American Physical Society and the Dirac Medal from the ICTP in 2018. He was a co-editor of the Annual Review of Condensed Matter Physics from 2017–2019.

Spinons are one of three quasiparticles, along with holons and orbitons, that electrons in solids are able to split into during the process of spin–charge separation, when extremely tightly confined at temperatures close to absolute zero. The electron can always be theoretically considered as a bound state of the three, with the spinon carrying the spin of the electron, the orbiton carrying the orbital location and the holon carrying the charge, but in certain conditions they can behave as independent quasiparticles.

In quantum mechanics, fractionalization is the phenomenon whereby the quasiparticles of a system cannot be constructed as combinations of its elementary constituents. One of the earliest and most prominent examples is the fractional quantum Hall effect, where the constituent particles are electrons but the quasiparticles carry fractions of the electron charge. Fractionalization can be understood as deconfinement of quasiparticles that together are viewed as comprising the elementary constituents. In the case of spin–charge separation, for example, the electron can be viewed as a bound state of a 'spinon' and a 'chargon', which under certain conditions can become free to move separately.

In condensed matter physics, quantum oscillations describes a series of related experimental techniques used to map the Fermi surface of a metal in the presence of a strong magnetic field. These techniques are based on the principle of Landau quantization of Fermions moving in a magnetic field. For a gas of free fermions in a strong magnetic field, the energy levels are quantized into bands, called the Landau levels, whose separation is proportional to the strength of the magnetic field. In a quantum oscillation experiment, the external magnetic field is varied, which causes the Landau levels to pass over the Fermi surface, which in turn results in oscillations of the electronic density of states at the Fermi level; this produces oscillations in the many material properties which depend on this, including resistance, Hall resistance, and magnetic susceptibility. Observation of quantum oscillations in a material is considered a signature of Fermi liquid behaviour.

Orbitons are one of three quasiparticles, along with holons and spinons, that electrons in solids are able to split into during the process of spin–charge separation, when extremely tightly confined at temperatures close to absolute zero. The electron can always be theoretically considered as a bound state of the three, with the spinon carrying the spin of the electron, the orbiton carrying the orbital location and the holon carrying the charge, but in certain conditions they can become deconfined and behave as independent particles.

Superfluidity is the characteristic property of a fluid with zero viscosity which therefore flows without any loss of kinetic energy. When stirred, a superfluid forms vortices that continue to rotate indefinitely. Superfluidity occurs in two isotopes of helium when they are liquefied by cooling to cryogenic temperatures. It is also a property of various other exotic states of matter theorized to exist in astrophysics, high-energy physics, and theories of quantum gravity. The theory of superfluidity was developed by Soviet theoretical physicists Lev Landau and Isaak Khalatnikov.

A leviton is a collective excitation of a single electron within a metal. It has been mostly studied in two-dimensional electron gases alongside quantum point contacts. The main feature is that the excitation produces an electron pulse without the creation of electron holes. The time-dependence of the pulse is described by a Lorentzian distribution created by a pulsed electric potential.

Bose–Einstein condensation can occur in quasiparticles, particles that are effective descriptions of collective excitations in materials. Some have integer spins and can be expected to obey Bose–Einstein statistics like traditional particles. Conditions for condensation of various quasiparticles have been predicted and observed. The topic continues to be an active field of study.

References

- 1 2 3 Clara Moskowitz (26 February 2014). "Meet the Dropleton—a "Quantum Droplet" That Acts Like a Liquid". Scientific American . Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- ↑ A. E. Almand-Hunter; H. Li; S. T. Cundiff; M. Mootz; M. Kira & S. W. Koch (26 February 2014). "Quantum droplets of electrons and holes". Nature . 506 (7489): 471–475. Bibcode:2014Natur.506..471A. doi:10.1038/nature12994. PMID 24572422.