Osgyth was a Mercian noblewoman and prioress, venerated as an English saint since the 8th century, from soon after her death. She is primarily commemorated in the village of St Osyth, in Essex, near Colchester. Alternative spellings of her name include Sythe, Othith and Ositha. Born of a noble family, she became a nun and founded a priory near Chich which was later named after her.

Lady Elizabeth de Montfort, Baroness Montagu was an English noblewoman.

Binsey is a small village on the west side of Oxford, in Oxfordshire, England. It lies on the banks of the River Thames about 1.5 miles (2.4 km) northwest of the centre of Oxford, on the opposite side of the river from Port Meadow and about 1 mile (1.6 km) southwest of the ruins of Godstow Abbey.

Godstow is a hamlet about 2.5 miles (4 km) northwest of the centre of Oxford. It lies on the banks of the River Thames between the villages of Wolvercote to the east and Wytham to the west. The ruins of Godstow Abbey, also known as Godstow Nunnery, are here. A bridge spans the Thames and the Trout Inn is at the foot of the bridge across the river from the abbey ruins. There is also a weir and Godstow lock.

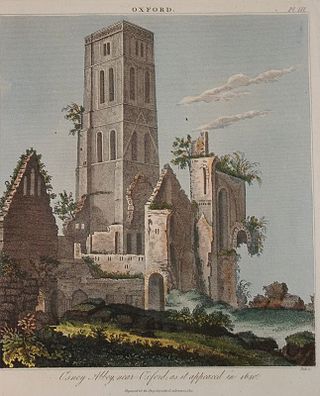

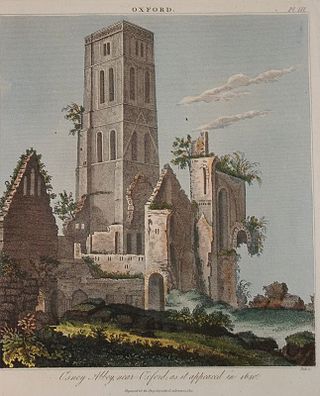

Osney Abbey or Oseney Abbey, later Osney Cathedral, was a house of Augustinian canons at Osney in Oxfordshire. The site is south of the modern Botley Road, down Mill Street by Osney Cemetery, next to the railway line just south of Oxford station. It was founded as a priory in 1129, becoming an abbey around 1154. It was dissolved in 1539 but was created a cathedral, the last abbot Robert King becoming the first Bishop of Oxford. The see was transferred to the new foundation of Christ Church in 1545 and the building fell into ruin. It was one of the four renowned monastic houses of medieval Oxford, along with St Frideswide's Priory, Rewley and Godstow.

Woodeaton or Wood Eaton is a village and civil parish about 4 miles (6.4 km) northeast of Oxford, England. It also has a special needs school called Woodeaton Manor School.

Saint Mildrith, also Mildthryth, Mildryth and Mildred,, was a 7th- and 8th-century Anglo-Saxon abbess of the Abbey at Minster-in-Thanet, Kent. She was declared a saint after her death, and, in 1030, her remains were moved to Canterbury.

St Frideswide's Priory was established as a priory of Augustinian canons regular in Oxford in 1122. The priory was established by Gwymund, chaplain to Henry I of England. Among its most illustrious priors were the writers Robert of Cricklade and Philip of Oxford.

Beorhthelm was an Anglo-Saxon saint about whom the only evidence is legendary. He is said to have had a hermitage on the island of Bethnei, which later became the town of Stafford. Later he went to a more hilly area, possibly near Ilam, where he died. Beorhthelm (Bertram) of Stafford is venerated as a saint in the Eastern Orthodox Church and Catholic Church, with a feast day on 10 August.

Piddington is a village and civil parish about 4.5 miles (7 km) southeast of Bicester in Oxfordshire, England. It lies close to the border with Buckinghamshire. Its toponym has been attributed to the Old English Pyda's tun. The 2011 Census recorded the parish's population as 370.

Saint Eanswith, also spelled Eanswythe or Eanswide, was an Anglo-Saxon princess, who is said to have founded Folkestone Priory, one of the first Christian monastic communities for women in Britain. Her possible remains were the subject of research, published in 2020.

Domne Eafe, also Domneva, Domne Éue, Æbbe, Ebba, was, according to the Kentish royal legend, a granddaughter of King Eadbald of Kent and the foundress of the double monastery of Minster in Thanet Priory at Minster-in-Thanet during the reign of her cousin King Ecgberht of Kent. A 1000-year-old confusion with her sister Eormenburg means she is often now known by that name. Married to Merewalh of Mercia, she had at least four children. When her two brothers, Æthelred and Æthelberht, were murdered she obtained the land in Thanet to build an abbey, from a repentant King Ecgberht. Her three daughters all went on to become abbesses and saints, the most famous of which, Mildrith, ended up with a shrine in St Augustine's Abbey, Canterbury.

Æbbe was a saint venerated in medieval Oxfordshire. St Ebbe's church in the southern English city of Oxford had been verifiably dedicated to the saint by 1091. It is believed that she represents a rare southern expression of the cult of the Northumbrian abbess and saint, Æbbe of Coldingham, to whom the church at Shelswell, also in Oxfordshire, was dedicated.

Repton Abbey was an Anglo-Saxon Benedictine abbey in Derbyshire, England. Founded in the 7th century, the abbey was a double monastery, a community of both monks and nuns. The abbey is noted for its connections to various saints and Mercian royalty; two of the thirty-seven Mercian Kings were buried within the abbey's crypt. The abbey was abandoned in 873, when Repton was overrun by the invading Great Heathen Army.

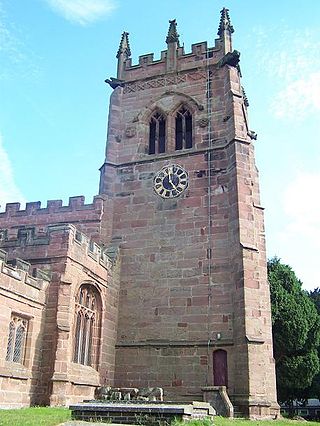

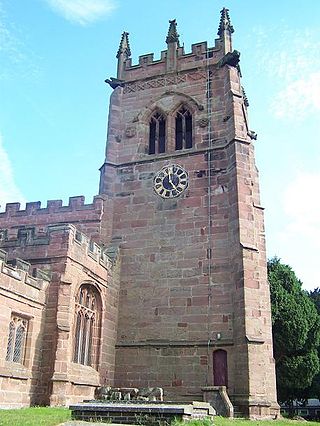

Osburh was a Saint in Coventry, probably Anglo-Saxon but see below. Nothing about her life has survived to the present day. Her mortal remains were enshrined at Coventry. Close to the Forest of Arden, Coventry was at that time a tiny settlement.

Dida of Eynsham was a 7th-century sub-king of the Mercian territory around Oxford, near the Chilterns. Little is known of his life, although he is mentioned briefly in the various Anglo-Saxon chronicles, and he has been purported, since ancient times, to be the father of St Frideswide, patron saint of Oxford.

Robert of Cricklade was a medieval English writer and prior of St Frideswide's Priory in Oxford. He was a native of Cricklade and taught before becoming a cleric. He wrote several theological works as well as a lost biography of Thomas Becket, the murdered Archbishop of Canterbury.

Oxfordshire Day is celebrated on 19 October to promote the historic English county of Oxfordshire. It is also the principal feast day of the patron saint of the city and university of Oxford, St Frideswide.

Philip of Oxford was an Augustinian canon and head of the Priory of St Frideswide, Oxford.

Catherine Dammartin was a nun in Metz who left her convent, adopted evangelical views, and married Peter Martyr Vermigli. She is buried with Frideswide, the patron saint of Oxford.