The use of toxic chemicals as weapons dates back thousands of years, but the first large-scale use of chemical weapons was during World War I. They were primarily used to demoralize, injure, and kill entrenched defenders, against whom the indiscriminate and generally very slow-moving or static nature of gas clouds would be most effective. The types of weapons employed ranged from disabling chemicals, such as tear gas, to lethal agents like phosgene, chlorine, and mustard gas. This chemical warfare was a major component of the first global war and first total war of the 20th century. The killing capacity of gas was limited, with about 90,000 fatalities from a total of 1.3 million casualties caused by gas attacks. Gas was unlike most other weapons of the period because it was possible to develop countermeasures, such as gas masks. In the later stages of the war, as the use of gas increased, its overall effectiveness diminished. The widespread use of these agents of chemical warfare, and wartime advances in the composition of high explosives, gave rise to an occasionally expressed view of World War I as "the chemist's war" and also the era where weapons of mass destruction were created.

The Capture of Hill 60 took place near Hill 60 south of Ypres on the Western Front, during the First World War. Hill 60 had been captured by the German 30th Division on 11 November 1914, during the First Battle of Ypres. Initial French preparations to raid the hill were continued by the British 28th Division, which took over the line in February 1915 and then by the 5th Division. The plan was expanded into an ambitious attempt to capture the hill, despite advice that Hill 60 could not be held unless the nearby Caterpillar ridge was also occupied. It was found that Hill 60 was the only place in the area not waterlogged and a French 3 ft × 2 ft mine gallery was extended.

The Battle of Loos took place from 25 September to 8 October 1915 in France on the Western Front, during the First World War. It was the biggest British attack of 1915, the first time that the British used poison gas and the first mass engagement of New Army units. The French and British tried to break through the German defences in Artois and Champagne and restore a war of movement. Despite improved methods, more ammunition and better equipment, the Franco-British attacks were largely contained by the Germans, except for local losses of ground. The British gas attack failed to neutralize the defenders and the artillery bombardment was too short to destroy the barbed wire or machine gun nests. German tactical defensive proficiency was still dramatically superior to the British offensive planning and doctrine, resulting in a British defeat.

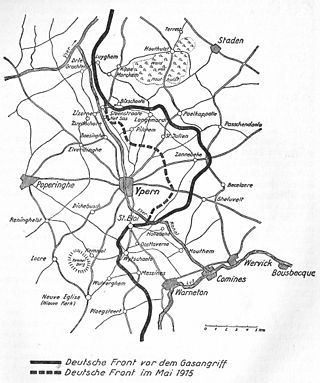

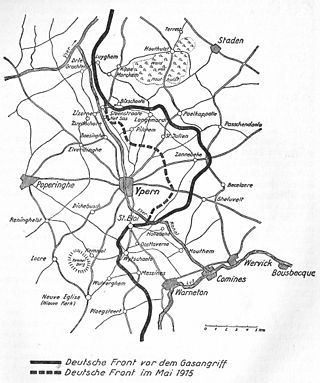

During the First World War, the Second Battle of Ypres was fought from 22 April – 25 May 1915 for control of the tactically important high ground to the east and south of the Flemish town of Ypres in western Belgium. The First Battle of Ypres had been fought the previous autumn. The Second Battle of Ypres was the first mass use by Germany of poison gas on the Western Front.

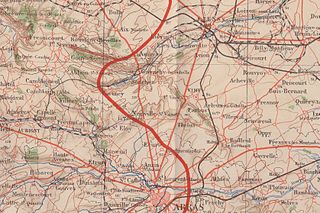

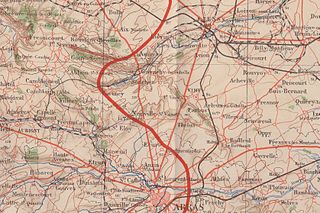

The first day on the Somme, 1 July 1916, was the beginning of the Battle of Albert (1–13 July), the name given by the British to the first two weeks of the 141 days of the Battle of the Somme in the First World War. Nine corps of the French Sixth Army and the British Fourth and Third armies attacked the German 2nd Army from Foucaucourt south of the Somme, northwards across the Somme and the Ancre to Serre and at Gommecourt, 2 mi (3.2 km) beyond, in the Third Army area. The objective of the attack was to capture the German first and second defensive positions from Serre south to the Albert–Bapaume road and the first position from the road south to Foucaucourt.

The Second Battle of Artois from 9 May to 18 June 1915, took place on the Western Front during the First World War. A German-held salient from Reims to Amiens had been formed in 1914 which menaced communications between Paris and the unoccupied parts of northern France. A reciprocal French advance eastwards in Artois could cut the rail lines supplying the German armies between Arras and Reims. French operations in Artois, Champagne and Alsace from November–December 1914, led General Joseph Joffre, Generalissimo and head of Grand Quartier Général (GQG), to continue the offensive in Champagne against the German southern rail supply route and to plan an offensive in Artois against the lines from Germany supplying the German armies in the north.

The Gas Attacks at Hulluch were two German cloud gas attacks on British troops during World War I, from 27 to 29 April 1916, near the village of Hulluch, 1 mi (1.6 km) north of Loos in northern France. The gas attacks were part of an engagement between divisions of the II Royal Bavarian Corps and divisions of the British I Corps.

The Battle of Messines was an attack by the British Second Army, on the Western Front, near the village of Messines in West Flanders, Belgium, during the First World War. The Nivelle Offensive in April and May had failed to achieve its more grandiose aims, had led to the demoralisation of French troops and confounded the Anglo-French strategy for 1917. The attack forced the Germans to move reserves to Flanders from the Arras and Aisne fronts, relieving pressure on the French.

The Battle of Hill 70 took place in the First World War between the Canadian Corps and five divisions of the German 6th Army. The battle took place along the Western Front on the outskirts of Lens in the Nord-Pas-de-Calais region of France between 15 and 25 August 1917.

The actions of the Hohenzollern Redoubt took place on the Western Front in World War I from 13 to 19 October 1915, at the Hohenzollern Redoubt near Auchy-les-Mines in France. In the aftermath of the Battle of Loos, the 9th (Scottish) Division captured the strongpoint and then lost it to a German counter-attack. The British attack on 13 October failed and resulted in 3,643 casualties, mostly in the first few minutes. In the History of the Great War, James Edmonds wrote that "The fighting [from 13 to 14 October] had not improved the general situation in any way and had brought nothing but useless slaughter of infantry".

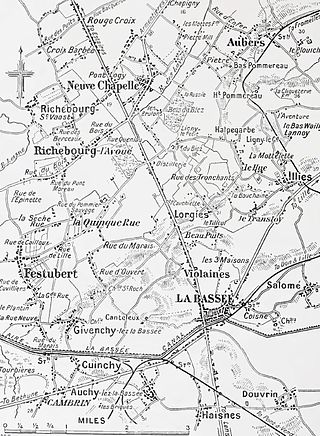

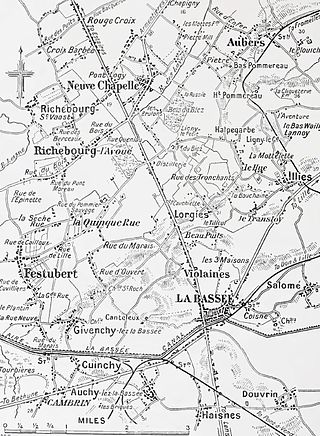

The Battle of La Bassée was fought by German and Franco-British forces in northern France in October 1914, during reciprocal attempts by the contending armies to envelop the northern flank of their opponent, which has been called the Race to the Sea. The German 6th Army took Lille before a British force could secure the town and the 4th Army attacked the exposed British flank further north at Ypres. The British were driven back and the German army occupied La Bassée and Neuve Chapelle. Around 15 October, the British recaptured Givenchy-lès-la-Bassée but failed to recover La Bassée.

The Battle of Pilckem Ridge was the opening attack of the Third Battle of Ypres in the First World War. The British Fifth Army, supported by the Second Army on the southern flank and the French 1reArmée on the northern flank, attacked the German 4th Army, which defended the Western Front from Lille northwards to the Ypres Salient in Belgium and on to the North Sea coast. On 31 July, the Anglo-French armies captured Pilckem Ridge and areas on either side, the French attack being a great success. After several weeks of changeable weather, heavy rain fell during the afternoon of 31 July.

VI Corps was an army corps of the British Army in the First World War. It was first organised in June 1915 and fought throughout on the Western Front. It was briefly reformed during the Second World War to command forces based in Northern Ireland, but was reorganized as British Forces in Ireland one month later.

The Gas attacks at Wulverghem were German cloud gas releases during the First World War on British troops at Wulverghem in the municipality of Heuvelland, near Ypres in the Belgian province of West Flanders. The gas attacks were part of the sporadic fighting between battles in the Ypres Salient on the Western Front. The British Second Army held the ground from Messines Ridge northwards to Steenstraat and the divisions opposite the German XXIII Reserve Corps had received warnings of a gas attack. From 21 to 23 April, British artillery-fire exploded several gas cylinders in the German lines around Spanbroekmolen, which released greenish-yellow clouds. A gas alert was given on 25 April when the wind began to blow from the north-east and routine work was suspended; on 29 April, two German soldiers deserted and warned that an attack was imminent. Just after midnight on 30 April, the German attack began and over no man's land, a gas cloud drifted on the wind into the British defences, then south-west towards Bailleul.

The Hohenzollern Redoubt action, 2–18 March 1916 was fought on the Western Front during the First World War. The Hohenzollern Redoubt was a German defensive position north of Loos-en-Gohelle (Loos), a mining town north-west of Lens in France. The Redoubt was fought over by the British and German armies from the Battle of Loos to the beginning of the Battle of the Somme on 1 July 1916. Over the winter of 1915–1916, the 170th Tunnelling Company RE dug several galleries under the German lines in the area of the redoubt, which had changed hands several times since September 1915. In March 1916, the west side was held by the British and the east side was occupied by the Germans, with the front near a new German trench known as The Chord. No man's land had become a crater field and the Germans had an unobstructed view of the British positions from the Fosse 8 slag heap. The British front line was held by outposts to reduce the number of troops vulnerable to mine explosions and the strain of knowing that the ground could erupt at any moment.

In World War I, the area around Hooge on Bellewaerde Ridge, about 2.5 mi (4 km) east of Ypres in Flanders in Belgium, was one of the easternmost sectors of the Ypres Salient and was the site of much fighting between German and Allied forces.

The Actions of the Bluff were local operations in 1916 carried out in Flanders during the First World War by the German 4th Army and the British Second Army. The Bluff is a mound near St Eloi, south-east of Ypres in Belgium, created from a spoil heap made during the digging of the Ypres–Comines Canal before the war. From 14 to 15 February and on 2 March 1916, the Germans and the British fought for control of the Bluff, the Germans capturing the mound and defeating counter-attacks only for the British to recapture it and a stretch of the German front line, after pausing to prepare a set-piece attack.

Hill 60 is a World War I battlefield memorial site and park in the Zwarteleen area of Zillebeke south of Ypres, Belgium. It is located about 4.6 kilometres (2.9 mi) from the centre of Ypres and directly on the railway line to Comines. Before the First World War the hill was known locally as Côte des Amants. The site comprises two areas of raised land separated by the railway line; the northern area was known by soldiers as Hill 60 while the southern part was known as The Caterpillar.

The Actions of St Eloi Craters from 27 March to 16 April 1916, were local operations in the Ypres Salient of Flanders, during the First World War by the German 4th Army and the British Second Army. Sint-Elooi is a village about 5 km (3.1 mi) south of Ypres in Belgium. The British dug six galleries under no man's land, placed large explosive charges under the German defences and blew them at 4:15 a.m. on 27 March. The 27th Division captured all but craters 4 and 5. The 46th Reserve Division counter-attacked but the British captured craters 4 and 5 on 30 March. The Canadian Corps took over, despite the disadvantage of relieving troops in action.

The small box respirator was the initial compact version of the recent gas mask. In late 1916, the respirator was introduced by the British with the purpose to provide reliable protection against chlorine and phosgene gas. The respirator offered a first line of defense against the gas. A later and more toxic gas, Mustard Gas, was created by Germans and was a vesicant that burnt the skin of individuals that were exposed to it. Death rates were high with exposure to both the mixed phosgene chlorine and mustard gas, however with soldiers having readily available access to the small box respirator, death rates had lowered significantly. Light and reasonably fitting, the respirator was a key piece of equipment to readily protect the respiratory health of soldiers on the battlefield.