The Enantiornithes, also known as enantiornithines or enantiornitheans in literature, are a group of extinct avialans, the most abundant and diverse group known from the Mesozoic era. Almost all retained teeth and clawed fingers on each wing, but otherwise looked much like modern birds externally. Over eighty species of Enantiornithes have been named, but some names represent only single bones, so it is likely that not all are valid. The Enantiornithes became extinct at the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary, along with Hesperornithes and all other non-avian dinosaurs.

Gobipteryx is a genus of prehistoric bird from the Campanian Age of the Late Cretaceous Period. It is not known to have any direct descendants. Like the rest of the enantiornithes clade, Gobipteryx is thought to have gone extinct near the end of the Cretaceous.

The Barun Goyot Formation is a geological formation dating to the Late Cretaceous Period. It is located within and is widely represented in the Gobi Desert Basin, in the Ömnögovi Province of Mongolia.

Elongatoolithus is an oogenus of dinosaur eggs found in the Late Cretaceous formations of China and Mongolia. Like other elongatoolithids, they were laid by small theropods, and were cared for and incubated by their parents until hatching. They are often found in nests arranged in multiple layers of concentric rings. As its name suggests, Elongatoolithus was a highly elongated form of egg. It is historically significant for being among the first fossil eggs given a parataxonomic name.

Dendroolithus is an oogenus of Dendroolithid dinosaur egg found in the late Cenomanian Chichengshan Formation, in the Gong-An-Zhai and Santonian Majiacun Formations of China and the Maastrichtian Nemegt and Campanian Barun Goyot Formation of Mongolia. They can be up to 162 mm long and 130 mm wide. These eggs may have been laid by a Therizinosaur, Sauropod, or Ornithopod. The oospecies "D." shangtangensis was originally classified as Dendroolithus, however, it has since been moved to its own distinct oogenus, Similifaveoloolithus. This oogenus is related with embryos of the theropod Torvosaurus

Dictyoolithus is an oogenus of dinosaur egg from the Cretaceous of China. It is notable for having over five superimposed layers of eggshell units. Possibly, it was laid by megalosauroid dinosaurs.

Macroelongatoolithus is an oogenus of large theropod dinosaur eggs, representing the eggs of giant caenagnathid oviraptorosaurs. They are known from Asia and from North America. Historically, several oospecies have been assigned to Macroelongatoolithus, however they are all now considered to be a single oospecies: M. carlylensis.

Macroolithus is an oogenus of dinosaur egg belonging to the oofamily Elongatoolithidae. The type oospecies, M. rugustus, was originally described under the now-defunct oogenus name Oolithes. Three other oospecies are known: M. yaotunensis, M. mutabilis, and M. lashuyuanensis. They are relatively large, elongated eggs with a two-layered eggshell. Their nests consist of large, concentric rings of paired eggs. There is evidence of blue-green pigmentation in its shell, which may have helped camouflage the nests.

Subtiliolithus is an oogenus of fossil egg from the Nemegt Formation of Mongolia and the Ohyamashimo Formation of Japan. The eggs are notable for a very thin eggshell. It contains three oospecies: S. hyogoensis, S. kachchhensis and S. microtuberculatus. They were originally classified as a distinct oofamily, Subtiliolithidae, but numerous similarities to Laevisoolithus have led to their reclassification as Laevisoolithid eggs. A complete skeleton of Nanantius valifanovi was found associated with Subtiliolithus eggshells, indicating that the oogenus represents eggs of enantiornithine birds.

Continuoolithus is an oogenus of dinosaur egg found in the late Cretaceous of North America. It is most commonly known from the late Campanian of Alberta and Montana, but specimens have also been found dating to the older Santonian and the younger Maastrichtian. It was laid by an unknown type of theropod. These small eggs are similar to the eggs of oviraptorid dinosaurs, but have a distinctive type of ornamentation.

Ageroolithus is an oogenus of dinosaur egg. It may have been laid by a theropod.

Dispersituberoolithus is an oogenus of fossil egg, which may have been laid by a bird or non-avian theropod.

Egg fossils are the fossilized remains of eggs laid by ancient animals. As evidence of the physiological processes of an animal, egg fossils are considered a type of trace fossil. Under rare circumstances a fossil egg may preserve the remains of the once-developing embryo inside, in which case it also contains body fossils. A wide variety of different animal groups laid eggs that are now preserved in the fossil record beginning in the Paleozoic. Examples include invertebrates like ammonoids as well as vertebrates like fishes, possible amphibians, and reptiles. The latter group includes the many dinosaur eggs that have been recovered from Mesozoic strata. Since the organism responsible for laying any given egg fossil is frequently unknown, scientists classify eggs using a parallel system of taxonomy separate from but modeled after the Linnaean system. This "parataxonomy" is called veterovata.

Sankofa is an oogenus of prismatoolithid egg. They are fairly small, smooth-shelled, and asymmetrical. Sankofa may represent the fossilized eggs of a transitional species between non-avian theropods and birds.

Microolithus is an oogenus of fossil bird egg from Wyoming, with preserved embryonic remains inside some of its specimens.

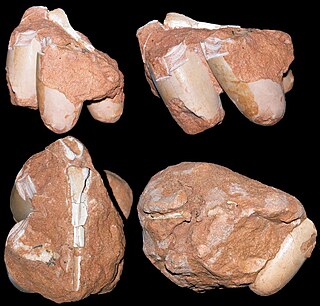

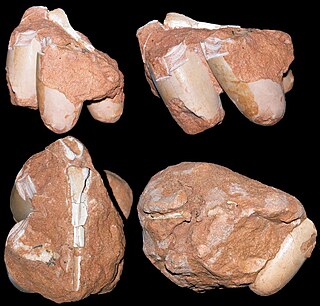

Styloolithus is an oogenus of highly distinctive fossil egg from the Upper Cretaceous Djadokhta Formation and the Barun Goyot Formation in Mongolia.

Elongatoolithidae is an oofamily of fossil eggs, representing the eggs of oviraptorosaurs. They are known for their highly elongated shape. Elongatoolithids have been found in Europe, Asia, and both North and South America.

Dictyoolithidae is an oofamily of dinosaur eggs which have a distinctive reticulate organization of their eggshell units. They are so far known only from Cretaceous formations in China.

Nipponoolithus is an oogenus of fossil egg native to Japan. It is one of the smallest known dinosaur eggs, and was probably laid by some kind of non-avian maniraptor.

Nanhsiungoolithus is an oogenus of dinosaur egg from the late Cretaceous of China. It belongs to the oofamily Elongatoolithidae, which means that it was probably laid by an oviraptorosaur, though so far no skeletal remains have been discovered in association with Nanhsiungoolithus. The oogenus contains only a single described oospecies, N. chuetienensis. It is fairly rare, only being know from two partially preserved nests and a few eggshell fragments.