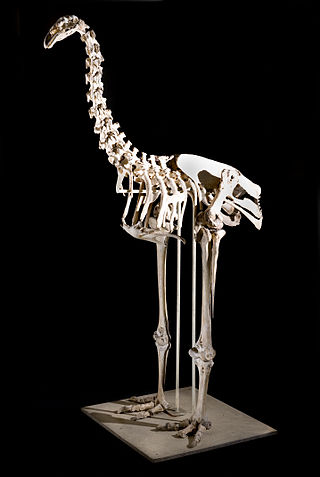

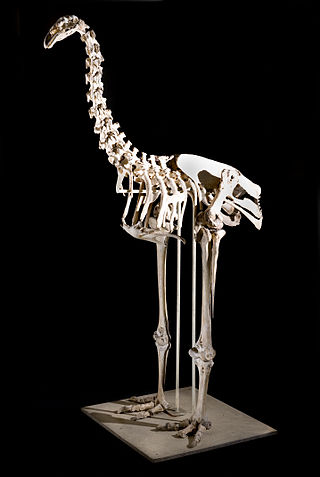

Moa are an extinct group of flightless birds formerly endemic to New Zealand. During the Late Pleistocene-Holocene, there were nine species. The two largest species, Dinornis robustus and Dinornis novaezelandiae, reached about 3.6 metres (12 ft) in height with neck outstretched, and weighed about 230 kilograms (510 lb) while the smallest, the bush moa, was around the size of a turkey. Estimates of the moa population when Polynesians settled New Zealand circa 1300 vary between 58,000 and approximately 2.5 million.

Haast's eagle is an extinct species of eagle that lived in the South Island of New Zealand, commonly accepted to be the pouākai of Māori mythology. It is the largest eagle known to have existed, with an estimated weight of 10–18 kilograms, compared to the next-largest and extant harpy eagle, at up to 9 kg (20 lb). Its massive size is explained as an evolutionary response to the size of its prey—the flightless moa—the largest of which could weigh 200 kg (440 lb). Haast's eagle became extinct around 1445, following the arrival of the Māori, who hunted moa to extinction, introduced the Polynesian rat, and destroyed large tracts of forest by fire.

Ratites are a polyphyletic group consisting of all birds within the infraclass Palaeognathae that lack keels and cannot fly. They are mostly large, long-necked, and long-legged, the exception being the kiwi, which is also the only nocturnal extant ratite.

Elephant birds are extinct flightless birds belonging to the order Aepyornithiformes that were native to the island of Madagascar. They are thought to have gone extinct around AD 1000, likely as a result of human activity. Elephant birds comprised three species, one in the genus Mullerornis, and two in Aepyornis.Aepyornis maximus is possibly the largest bird to have ever lived, with their eggs being the largest known for any amniote. Elephant birds are palaeognaths, and their closest living relatives are kiwi, suggesting that ratites did not diversify by vicariance during the breakup of Gondwana but instead convergently evolved flightlessness from ancestors that dispersed more recently by flying.

Flightless birds are birds that cannot fly, as they have, through evolution, lost the ability to. There are over 60 extant species, including the well-known ratites and penguins. The smallest flightless bird is the Inaccessible Island rail. The largest flightless bird, which is also the largest living bird in general, is the common ostrich.

The adzebills, genus Aptornis, were two closely related bird species, the North Island adzebill,, and the South Island adzebill,, of the extinct family Aptornithidae. The family was endemic to New Zealand. A tentative fossil species,, is known from the Miocene Saint Bathans fauna.

The bush moa, little bush moa, or lesser moa is an extinct species of moa from the family Emeidae endemic to New Zealand.

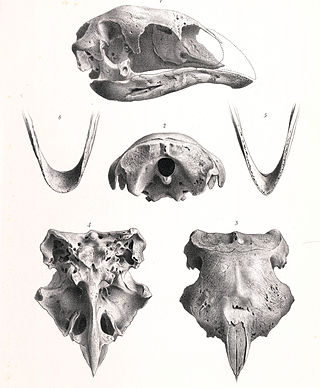

The upland moa is an extinct species of moa that was endemic to New Zealand. The species was named by Richard Owen in 1883, and belongs to the ratites, a group of flightless birds with no keel on the sternum. Of all moa species, Megalapteryx didinus has the best-preserved specimens, which occasionally also show impressions of soft tissue. The upland moa lived on the South Island of New Zealand, and was predominantly found in alpine and sub-alpine environment where it fed on flowers, herbs and other vegetation. After the Māori arrived in New Zealand and started hunting it, the species went extinct around 1500 CE. It was the last remaining moa species.

Palaeognathae is an infraclass of birds, called paleognaths or palaeognaths, within the class Aves of the clade Archosauria. It is one of the two extant infraclasses of birds, the other being Neognathae, both of which form Neornithes. Palaeognathae contains five extant orders consisting of four flightless lineages, termed ratites, and one flying lineage, the Neotropic tinamous. There are 47 species of tinamous, five of kiwis (Apteryx), three of cassowaries (Casuarius), one of emus (Dromaius), two of rheas (Rhea) and two of ostriches (Struthio). Recent research has indicated that paleognaths are monophyletic but the traditional taxonomic split between flightless and flighted forms is incorrect; tinamous are within the ratite radiation, meaning flightlessness arose independently multiple times via parallel evolution.

The eastern moa is an extinct species of moa that was endemic to New Zealand.

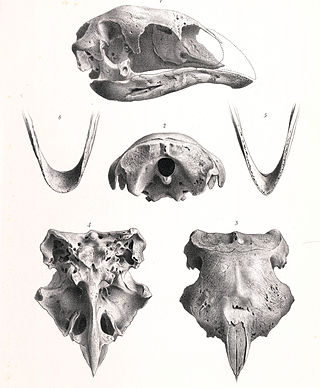

Pachyornis is an extinct genus of ratites from New Zealand which belonged to the moa family. Like all ratites it was a member of the order Struthioniformes. The Struthioniformes are flightless birds with a sternum without a keel. They also have a distinctive palate. This genus contains three species, and are part of the Anomalopteryginae or lesser moa subfamily. Pachyornis moa were the stoutest and most heavy-legged genus of the family, the most notable species being Pachyornis elephantopus - the heavy-footed moa. They were generally similar to the eastern moa or the broad-billed moa of the genus Euryapteryx, but differed in having a pointed bill and being more heavyset in general. At least one species is assumed to have had a crest of long feathers on its head. The species became rapidly extinct following human colonization of New Zealand, with the possible exception of P. australis, which may have already been extinct by then - although the most recent moa skeleton ever described is a partial skeleton of this species, radiocarbon dated to between 1396 and 1442.

The crested moa is an extinct species of moa. It is one of the 9 known species of moa to have existed.

The heavy-footed moa is a species of moa from the lesser moa family. The heavy-footed moa was widespread only in the South Island of New Zealand, and its habitat was the lowlands. The moa were ratites, flightless birds with a sternum without a keel. They also have a distinctive palate. The origin of these birds is becoming clearer as it is now believed that early ancestors of these birds were able to fly and flew to the southern areas in which they have been found.

The North Island giant moa is an extinct moa in the genus Dinornis, known in Māori as kuranui. Even though it might have walked with a lowered posture, standing upright, it would have been the tallest bird ever to exist, with a height estimated up to 3.6 metres (12 ft).

The South Island giant moa is an extinct species of moa in the genus Dinornis, known in Māori by the name moa nunui. It was one of the tallest-known bird species to walk the Earth, exceeded in weight only by the heavier but shorter elephant bird of Madagascar.

The broad-billed moa, stout-legged moa or coastal moa is an extinct species of moa that was endemic to New Zealand.

Notopalaeognathae is a clade that contains the order Rheiformes (rheas), the clade Novaeratitae, and the clade Dinocrypturi. Notopalaeognathae was named by Yuri et al. (2013) and defined in the PhyloCode by Sangster et al. (2022) as "the least inclusive crown clade containing Rhea americana, Tinamus major, and Apteryx australis". The exact relationships of this group, including its recently extinct members, have only recently been uncovered. The two lineages endemic to New Zealand, the kiwis and the extinct moas, are not each other's closest relatives: the moas are most closely related to the Neotropical tinamous, and the kiwis are sister to the extinct elephant birds of Madagascar, with kiwis and elephant birds together sister to the cassowaries and emu of New Guinea and Australia. The South American rheas are either sister to all other notopalaeognaths or sister to Novaeratitae. The sister group to Notopalaeognathae is Struthionidae.