The Capitol Limited is a daily Amtrak train between Washington, D.C., and Chicago, running 764 miles (1,230 km) via Pittsburgh and Cleveland. Service began in 1981 and was named after the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad's Capitol Limited which ended in 1971 upon the formation of Amtrak. It carries the Amtrak train numbers 29 and 30, which were previously assigned to the discontinued National Limited.

A dining car or a restaurant car (English), also a diner, is a railroad passenger car that serves meals in the manner of a full-service, sit-down restaurant.

A bilevel car or double-decker coach is a type of rail car that has two levels of passenger accommodation as opposed to one, increasing passenger capacity.

The Southwest Chief is a long-distance passenger train operated by Amtrak on a 2,265-mile (3,645 km) route between Chicago and Los Angeles through the Midwest and Southwest via Kansas City, Albuquerque, and Flagstaff mostly on the BNSF's Southern Transcon, but branches off between Albuquerque and Kansas City via the Topeka, La Junta, Raton, and Glorieta Subdivision. Amtrak bills the route as one of its most scenic, with views of the Painted Desert and the Red Cliffs of Sedona, as well as the plains of Illinois, Missouri, Kansas, and Colorado.

The Broadway Limited was a passenger train operated by the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) between New York City and Chicago. It operated from 1912 to 1995. It was the Pennsylvania's premier train, competing directly with the New York Central Railroad's 20th Century Limited. The Broadway Limited continued operating after the formation of Penn Central (PC) in February 1968, one of the few long-distance trains to do so. PC conveyed the train to Amtrak in 1971, who operated it until 1995. The train's name referred not to Broadway in Manhattan, but rather to the "broad way" of PRR's four-track right-of-way along the majority of its route.

The Superliner is a type of bilevel intercity railroad passenger car used by Amtrak, the national rail passenger carrier in the United States. Amtrak commissioned the cars to replace older single-level cars on its long-distance trains in the Western United States. The design was based on the Budd Hi-Level cars used by the Santa Fe Railway on its El Capitan trains. Pullman-Standard built 284 cars, known as Superliner I, from 1975 to 1981; Bombardier Transportation built 195, known as Superliner II, from 1991 to 1996. The Superliner I cars were the last passenger cars built by Pullman.

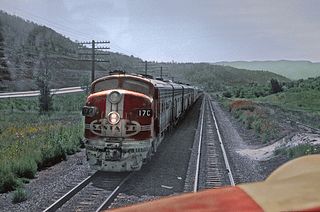

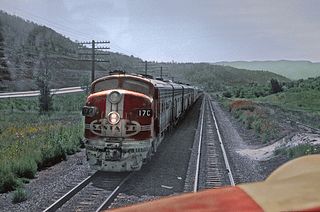

The Super Chief was one of the named passenger trains and the flagship of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway. The then-modern streamliner was touted in its heyday as "The Train of the Stars" because it often carried celebrities between Chicago, Illinois, and Los Angeles, California.

The City of Los Angeles was a streamlined passenger train between Chicago, Illinois, and Los Angeles, California via Omaha, Nebraska, and Ogden, Utah. Between Omaha and Los Angeles it ran on the Union Pacific Railroad; east of Omaha it ran on the Chicago and North Western Railway until October 1955 and on the Milwaukee Road thereafter. The train had number 103 westbound and number 104 eastbound.

The San Diegan was one of the named passenger trains of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway, and a “workhorse” of the railroad. Its 126-mile (203-kilometer) route ran from Los Angeles, California south to San Diego. It was assigned train Nos. 70–79.

A dome car is a type of railway passenger car that has a glass dome on the top of the car where passengers can ride and see in all directions around the train. It also can include features of a coach, lounge car, dining car, sleeping car or observation. Beginning in 1945, dome cars were primarily used in the United States and Canada, though a small number were constructed in Europe for Trans Europ Express service.

The Budd Company was a 20th-century metal fabricator, a major supplier of body components to the automobile industry, and a manufacturer of stainless steel passenger rail cars, airframes, missile and space vehicles, and various defense products.

The El Capitan was a streamlined passenger train operated by the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway between Chicago, Illinois, and Los Angeles, California. It operated from 1938 to 1971; Amtrak retained the name until 1973. The El Capitan was the only all-coach or "chair car" to operate on the Santa Fe main line between Chicago and Los Angeles on the same fast schedule as the railroad's premier all-Pullman Super Chief. It was also the first train to receive the pioneering Hi-Level equipment with which it would become synonymous.

The Chief was an American long-distance named passenger train of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway that ran between Chicago, Illinois and Los Angeles, California. The Santa Fe initiated the Chief in 1926 to supplement the California Limited. In 1936 the Super Chief was introduced, after the Super Chief was relaunched in 1948 with daily departures from LA and Chicago it gradually eclipsed the Chief as the standard bearer of the Santa Fe because of its timetable oriented to the Raton Pass transit. For some the Chief and San Francisco Chief as deluxe integrated trains with both Pullman sleepers and fully reclining coach seating with all facilities; lounges and pleasure domes, available to all passengers were at least equal flagships better suited to the business and executive market. From the mid 1960s the super Chief was only a small entirely separate section of the El Capitan seated vista train, the El Capitan passengers having no access to the Super Chiefs expensive eateries and bars which selling point was exclusion and service. The Chief was discontinued in 1968 due to high operating costs, competition from airlines, and the loss of Postal Office contracts.

The Grand Canyon Limited was one of the named passenger trains of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway. It was train Nos. 23 & 24 between Chicago, Illinois, and Los Angeles, California.

The San Francisco Chief was a streamlined passenger train on the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway between Chicago and the San Francisco Bay Area. It ran from 1954 until 1971. The San Francisco Chief was the last new streamliner introduced by the Santa Fe, its first full train between Chicago and the Bay, the only Chicago–Bay Area train running over just one railroad, and at 2,555 miles (4,112 km) the longest run in the country on one railroad. The San Francisco Chief was one of many trains discontinued when Amtrak began operations in 1971.

The Golden Gate was one of the named passenger trains of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway. It ran on the railroad's Valley Division between Oakland and Bakersfield, California; its bus connections provided service between San Francisco and Los Angeles via California's San Joaquin Valley.

The Texas Chief was a passenger train operated by the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway between Chicago, Illinois, and Galveston, Texas. It was the first Santa Fe "Chief" outside the Chicago–Los Angeles routes. The Santa Fe conveyed the Texas Chief to Amtrak in 1971, which renamed it the Lone Star in 1974. The train was discontinued in 1979.

The Big Domes were a fleet of streamlined dome cars built by the Budd Company for the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway in 1954. Budd built a total of 14 cars in two batches. The Santa Fe operated all 14 on various streamlined trains until it conveyed its passenger trains to Amtrak in 1971. The Santa Fe retained one as a business car and sold the remaining 13 to the Auto-Train Corporation, which operated them for another ten years. All but two have been preserved in varying condition.

The Great Domes were a fleet of six streamlined dome lounge cars built by the Budd Company for the Great Northern Railway and Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad in 1955. The cars were used exclusively on the Empire Builder from their introduction in 1955 until the end of private passenger service in 1971. Amtrak retained all six cars and they continued to run on the Empire Builder before new Superliners displaced them at the end of the decade, after which they saw service elsewhere in the system before the last one being retired in 2019. The Great Domes were similar in design to the Big Domes Budd built for the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway.

The Gallery Car is a bilevel rail car, originally created by the Pullman Company as the Pullman Gallery Car. It has had five total different manufacturers since its creation, including Budd, St. Louis Car Company, Amerail, Nippon Sharyo and Canadian Vickers. These double-decker passenger car were built by Pullman-Standard during the 1950s to 1970s for various passenger rail operators in the United States.