Ranjit Singh was the founder and first maharaja of the Sikh Empire, ruling from 1801 until his death in 1839. He ruled the northwest Indian subcontinent in the early half of the 19th century. He survived smallpox in infancy but lost sight in his left eye. He fought his first battle alongside his father at age 10.

Diwan Dina Nath (1795—1857) was an official of the durbar of the Sikh Empire who served as the privy seal and finance minister in the court of Maharaja Ranjit Singh. He was conferred the title of Raja in 1847, eight years after the death of Ranjit Singh. Following the British victory in the First Sikh War, Dina Nath was made a member of the Council of Regency under the authority of the Governor-General of the East India Company. The British conferred the title of 'Raja' on him, hoping to make him an ally. He was one of six signatories to the 1849 Treaty of Lahore, which agreed to the surrender of "The Gem called the Koh-i-noor" by the Maharaja of Lahore, the ten-year-old Dalip Singh, to the Queen of England. The signatories, on behalf of the minor Dalip Singh, endorsed the treaty in return for being permitted to retain their jagirs.

Udasis, also spelt as Udasins, also known as Nanak Putras, are a religious sect of ascetic sadhus centred in northern India who follow a tradition known as Udasipanth. Becoming custodians of Sikh shrines in the 18th century, they were notable interpreters and spreaders of the Sikh philosophy during that time. However, their religious practices border on a syncretism of Sikhism and Hinduism, and they did not conform to the Khalsa standards as ordained by Guru Gobind Singh. When the Lahore Singh Sabha reformers, dominated by Tat Khalsa Sikhs, would hold them responsible for indulging in ritual practices antithetical to Sikhism, as well as personal vices and corruption, the Udasi mahants were expelled from the Sikh shrines.

The Sikh Empire was a regional power based in the Punjab region of the Indian subcontinent. It existed from 1799, when Maharaja Ranjit Singh captured Lahore, to 1849, when it was defeated and conquered by the British East India Company in the Second Anglo-Sikh War. It was forged on the foundations of the Khalsa from a collection of autonomous misls. At its peak in the 19th century, the empire extended from Gilgit and Tibet in the north to the deserts of Sindh in the south and from the Khyber Pass in the west to the Sutlej in the east as far as Oudh. It was divided into four provinces: Lahore, which became the Sikh capital; Multan; Peshawar; and Kashmir from 1799 to 1849. Religiously diverse, with an estimated population of 4.5 million in 1831, it was the last major region of the Indian subcontinent to be annexed by the British Empire.

Dal Khalsa was the name of the combined military forces of 11 Sikh misls that operated in the 18th century (1748–1799) in the Punjab region. It was established by Nawab Kapur Singh in late 1740s.

Maharaja Gulab Singh Jamwal (1792–1857) was the founder of Dogra dynasty and the first Maharaja of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, which was a part of Sikh Empire became the largest princely state under the British Raj, which was created after the defeat of the Sikh Empire in the First Anglo-Sikh War. During the war, Gulab Singh would later side with the British and end up becoming the Prime Minister of Sikh Empire. The Treaty of Amritsar (1846) formalised the transfer of all the lands in Kashmir that were ceded to them by the Sikhs by the Treaty of Lahore.

Majha is a region located in the central parts of the historical Punjab region, currently split between the republics of Pakistan and India. It extends north from the right banks of the river Beas, and reaches as far north as the river Jhelum. People of the Majha region are given the demonym "Mājhī" or "Majhail". Most inhabitants of the region speak the Majhi dialect, which is the basis of the standard register of the Punjabi language. The most populous city in the area is Lahore on the Pakistani side, and Amritsar on the Indian side of the border.

Guru Nanak founded the Sikh religion in the Punjab region of the northern part of the Indian subcontinent in the 15th century and opposed many traditional practices like fasting, Upanayana, idolatry, caste system, ascetism, azan, economic materialism, and gender discrimination.

Zorawar Singh was a military general of the Dogra Rajput ruler, Gulab Singh, who served as the Raja of Jammu under the Sikh Empire. He served as the governor (wazir-e-wazarat) of Kishtwar and extended the territories of the kingdom by conquering Ladakh and Baltistan. He also boldly attempted the conquest of Western Tibet but was killed in battle of To-yo during the Dogra-Tibetan war. In reference to his legacy of conquests in the Himalaya Mountains including Ladakh, Tibet, Baltistan and Skardu as General and Wazir, Zorowar Singh has been referred to as the "Napoleon of India", and "Conqueror of Ladakh".

The Sikh Khalsa Army, also known as Khalsaji or simply Sikh Army, was the military force of the Sikh Empire. With its roots in the Khalsa founded by Guru Gobind Singh, the army was later modernised on Franco-British principles by Maharaja Ranjit Singh. It was divided in three wings: the Fauj-i-Khas (elites), Fauj-i-Ain and Fauj-i-Be Qawaid (irregulars). Due to the lifelong efforts of the Maharaja and his European officers, it gradually became a prominent fighting force of Asia. Ranjit Singh changed and improved the training and organisation of his army. He reorganized responsibility and set performance standards in logistical efficiency in troop deployment, manoeuvre, and marksmanship. He reformed the staffing to emphasize steady fire over cavalry and guerrilla warfare, improved the equipment and methods of war. The military system of Ranjit Singh combined the best of both old and new ideas. He strengthened the infantry and the artillery. He paid the members of the standing army from treasury, instead of the Mughal method of paying an army with local feudal levies.

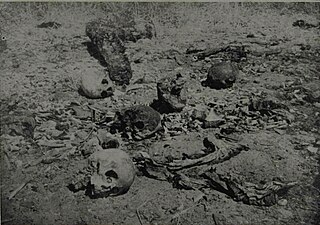

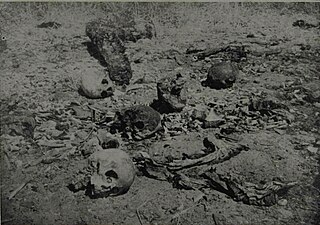

Chhota Ghallughara was a massacre of a significant proportion of the Sikh population by the Mughal Empire in 1746. The Mughal Army killed an estimated 7,000 Sikhs in these attacks while an additional 3,000 Sikhs were taken captive. Chhōtā Ghallūghārā is distinguished from the Vaddā Ghallūghārā, the greater massacre of 1762.

Sham Singh Attariwala was a general of the Sikh Empire.

The Singh Sabhā Movement, also known as the Singh Sabhā Lehar, was a Sikh movement that began in Punjab in the 1870s in reaction to the proselytising activities of Christians, Hindu reform movements and Muslims. The movement was founded in an era when the Sikh Empire had been dissolved and annexed by the British, the Khalsa had lost its prestige, and mainstream Sikhs were rapidly converting to other religions. The movement's aims were to "propagate the true Sikh religion and restore Sikhism to its pristine glory; to write and distribute historical and religious books of Sikhs; and to propagate Gurmukhi Punjabi through magazines and media." The movement sought to reform Sikhism and bring back into the Sikh fold the apostates who had converted to other religions; as well as to interest the influential British officials in furthering the Sikh community. At the time of its founding, the Singh Sabha policy was to avoid criticism of other religions and political matters.

The Afghan–Sikh wars spanned from 1748 to 1837 in the Indian subcontinent, and saw multiple phases of fighting between the Durrani Empire and the Sikh Empire, mainly in and around Punjab region. The conflict's origins stemmed from the days of the Dal Khalsa, and continued after the Emirate of Kabul succeeded the Durrani Empire.

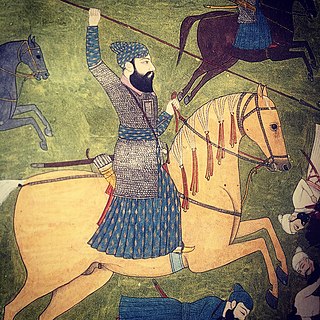

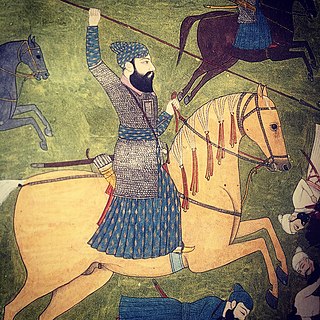

Banda Singh Bahadur; born Lachman Dev;, was a Sikh warrior and a general of the Khalsa Army. At age 15, he left home to become an ascetic, and was given the name Madho Das Bairagi. He established a monastery at Nānded, on the bank of the river Godāvarī. In 1707, Guru Gobind Singh accepted an invitation to meet Mughal Emperor Bahadur Shah I in southern India, he visited Banda Singh Bahadur in 1708. Banda became disciple of Guru Gobind Singh and was given a new name, Gurbaksh Singh(as written in Mahan Kosh), after the baptism ceremony. He is popularly known as Banda Singh Bahadur. He was given five arrows by the Guru as a blessing for the battles ahead. He came to Khanda, Sonipat and assembled a fighting force and led the struggle against the Mughal Empire.

Manawala is a city in Sheikhupura District, Punjab, Pakistan. It is situated on the Lahore-Sheikhupura-Faisalabad road.

Zafarnamah Ranjit Singh is a chronicle of the victories of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, written by Diwan Amar Nath.

The Punjab Archives is a repository of the non-current historical and cultural records of South Asia, located in Lahore, Punjab, Pakistan. It was established in 1924 under British Punjab and is currently under the jurisdiction of the Government of Punjab, Pakistan.

Diwan Bhawani Das was a high-ranking Hindu official under Durrani emperors, Zaman Shah and Shah Shujah. He later became the revenue minister of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, ruler of the powerful Sikh Empire.

In 1822, after Maharaja Ranjit Singh gave employment to the European mercenaries, the Fauj-i-Ain divided unequally into the Kampu-i-mu'alla and the Fauj-i-Khas. Of the two, the Kampu-i-mu'alla was the larger trained division of the Sikh Khalsa Army comprising infantry, cavalry and artillery, but principally the infantry and artillery. The men enrolled in the Kampu-i-mu'alla wore uniforms and received a salary from the royal treasury.