Rurik was a Varangian chieftain of the Rus' who, according to tradition, was invited to reign in Novgorod in the year 862. The Primary Chronicle states that Rurik was succeeded by his kinsman Oleg who was regent for his infant son Igor.

The Viking Age (793–1066 CE) was the period during the Middle Ages when Norsemen known as Vikings undertook large-scale raiding, colonising, conquest, and trading throughout Europe and reached North America. It followed the Migration Period and the Germanic Iron Age. The Viking Age applies not only to their homeland of Scandinavia but also to any place significantly settled by Scandinavians during the period. The Scandinavians of the Viking Age are often referred to as Vikings as well as Norsemen, although few of them were Vikings in the sense of being engaged in piracy.

Harald Sigurdsson, also known as Harald III of Norway and given the epithet Hardrada in the sagas, was King of Norway from 1046 to 1066. Additionally, he unsuccessfully claimed both the Danish throne until 1064 and the English throne in 1066. Before becoming king, Harald had spent around fifteen years in exile as a mercenary and military commander in Kievan Rus' and as a chief of the Varangian Guard in the Byzantine Empire. In his chronicle, Adam of Bremen called him the "Thunderbolt of the North".

The Norsemen were a North Germanic linguistic group of the Early Middle Ages, during which they spoke the Old Norse language. The language belongs to the North Germanic branch of the Indo-European languages and is the predecessor of the modern Germanic languages of Scandinavia. During the late eighth century, Scandinavians embarked on a large-scale expansion in all directions, giving rise to the Viking Age. In English-language scholarship since the 19th century, Norse seafaring traders, settlers and warriors have commonly been referred to as Vikings. Historians of Anglo-Saxon England distinguish between Norse Vikings (Norsemen) from Norway, who mainly invaded and occupied the islands north and north-west of Britain, as well as Ireland and western Britain, and Danish Vikings, who principally invaded and occupied eastern Britain.

Oleg, also known as Oleg the Wise, was a Varangian prince of the Rus' who became prince of Kiev, and laid the foundations of the Kievan Rus' state.

The Swedes were a North Germanic tribe who inhabited Svealand in central Sweden and one of the progenitor groups of modern Swedes, along with Geats and Gutes. They had their tribal centre in Gamla Uppsala.

The Varangian Guard was an elite unit of the Byzantine army from the tenth to the fourteenth century who served as personal bodyguards to the Byzantine emperors. The Varangian Guard was known for being primarily composed of recruits from Northern Europe, including mainly Norsemen from Scandinavia but also Anglo-Saxons from England. The recruitment of distant foreigners from outside Byzantium to serve as the emperor's personal guard was pursued as a deliberate policy, as they lacked local political loyalties and could be counted upon to suppress revolts by disloyal Byzantine factions.

Garðaríki or Garðaveldi was the Old Norse term used in the Middle Ages for the lands of Rus'. According to Göngu-Hrólfs saga, the name Hólmgarðaríki was synonymous with Garðaríki, and these names were used interchangeably in several other Old Norse stories.

The trade route from the Varangians to the Greeks was a medieval trade route that connected Scandinavia, Kievan Rus' and the Eastern Roman Empire. The route allowed merchants along its length to establish a direct prosperous trade with the Empire, and prompted some of them to settle in the territories of present-day Belarus, Russia and Ukraine. The majority of the route comprised a long-distance waterway, including the Baltic Sea, several rivers flowing into the Baltic Sea, and rivers of the Dnieper river system, with portages on the drainage divides. An alternative route was along the Dniester river with stops on the western shore of Black Sea. These more specific sub-routes are sometimes referred to as the Dnieper trade route and Dniester trade route, respectively.

Ingvar the Far-Travelled was a Swedish Viking who led an expedition that fought in the Kingdom of Georgia.

In the Middle Ages, the Volga trade route connected Northern Europe and Northwestern Russia with the Caspian Sea and the Sasanian Empire, via the Volga River. The Rus used this route to trade with Muslim countries on the southern shores of the Caspian Sea, sometimes penetrating as far as Baghdad. The powerful Volga Bulgars formed a seminomadic confederation and traded through the Volga river with Viking people of Rus' and Scandinavia and with the southern Byzantine Empire Furthermore, Volga Bulgaria, with its two cities Bulgar and Suvar east of what is today Moscow, traded with Russians and the fur-selling Ugrians. Chess was introduced to Medieval Rus via the Caspian-Volga trade routes from Persia and Arabia.

Yakun or Jakun, nicknamed the Blind, was a Varangian (Viking) leader who is mentioned in the Primary Chronicle and in the Kiev Pechersk Lavra. The chronicle tells that he arrived in Kievan Rus' in the year 1024 and fought in the Battle of Listven between the half-brothers Yaroslav I the Wise and Mstislav of Chernigov.

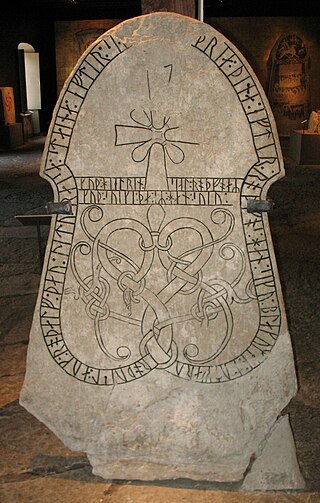

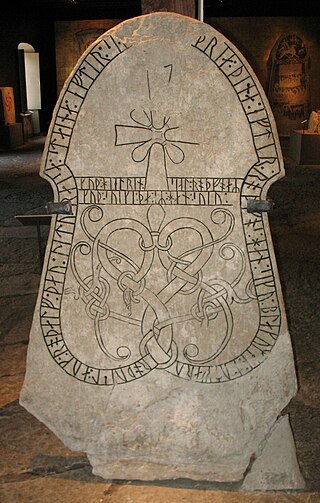

The Berezan' Runestone was discovered in 1905 by Ernst von Stern, professor at Odessa, on Berezan' Island where the Dnieper River meets the Black Sea. The runestone is 48 cm (19 in) wide, 47 cm (19 in) high and 12 cm (4.7 in) thick, and kept in the museum of Odesa. It was made by a Varangian (Viking) trader named Grani in memory of his business partner Karl. They were probably from Gotland, Sweden.

The Rus', also known as Russes, were a people in early medieval Eastern Europe. The scholarly consensus holds that they were originally Norsemen, mainly originating from present-day Sweden, who settled and ruled along the river-routes between the Baltic and the Black Seas from around the 8th to 11th centuries AD. In the 9th century, they formed the state of Kievan Rusʹ, where the ruling Norsemen along with local Finnic tribes gradually assimilated into the East Slavic population, with Old East Slavic becoming the common spoken language. Old Norse remained familiar to the elite until their complete assimilation by the second half of the 11th century, and in rural areas, vestiges of Norse culture persisted as late as the 14th and early 15th centuries, particularly in the north.

Rusʹ Khaganate, or kaganate of Rus is a name applied by some modern historians to a hypothetical polity suggested to have existed during a poorly documented period in the history of Eastern Europe between c. 830 and the 890s.

Kievan Rus', also known as Kyivan Rus', was a state and later an amalgam of principalities in Eastern and Northern Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century. The name was coined by Russian historians in the 19th century. Encompassing a variety of polities and peoples, including East Slavic, Norse, and Finnic, it was ruled by the Rurik dynasty, founded by the Varangian prince Rurik. The modern nations of Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine all claim Kievan Rus' as their cultural ancestor, with Belarus and Russia deriving their names from it, and the name Kievan Rus' derived from what is now the capital of Ukraine. At its greatest extent in the mid-11th century, Kievan Rus' stretched from the White Sea in the north to the Black Sea in the south and from the headwaters of the Vistula in the west to the Taman Peninsula in the east, uniting the East Slavic tribes.

The Varangians were Viking conquerors, traders and settlers, mostly from present-day Sweden. The Varangians settled in the territories of present-day Belarus, Russia and Ukraine from the 8th and 9th centuries, and established the state of Kievan Rus' as well as the principalities of Polotsk and Turov. They also formed the Byzantine Varangian Guard, which later also included Anglo-Saxons.

North Germanic peoples, Nordic peoples and in a medieval context Norsemen, were a Germanic linguistic group originating from the Scandinavian Peninsula. They are identified by their cultural similarities, common ancestry and common use of the Proto-Norse language from around 200 AD, a language that around 800 AD became the Old Norse language, which in turn later became the North Germanic languages of today.

Blakumen or Blökumenn were a people mentioned in Scandinavian sources dating from the 11th through 13th centuries. The name of their land, Blokumannaland, has also been preserved. Victor Spinei, Florin Curta, Florin Pintescu and other historians identify them as Romanians, while Omeljan Pritsak argues that they were Cumans. Judith Jesch adds the possibility that the terms meant "black men", the meaning of which is unclear. Historians identify Blokumannaland as the lands south of the Lower Danube which were inhabited by Vlachs in the Middle Ages, adding that the term may refer to either Wallachia or Africa in the modern Icelandic language.

Normanism and anti-Normanism are competing theories about the origin of Kievan Rus' that emerged in the 18th and 19th centuries concerning the narrative of the Viking Age in Eastern Europe. At the centre of the disagreement is the origin of the Varangian Rus', a people who travelled across and settled in Eastern Europe in the 8th and 9th centuries, and are considered by most modern historians to be of Scandinavian origin, but soon assimilated with the Slavs. The Normanist theory has been firmly established as mainstream, and modern Anti-Normanism is viewed as historical revisionism.