Written Chinese is a writing system that uses Chinese characters and other symbols to represent the Chinese languages. Chinese characters do not directly represent pronunciation, unlike letters in an alphabet or syllabograms in a syllabary. Rather, the writing system is morphosyllabic: characters are one spoken syllable in length, but generally correspond to morphemes in the language, which may either be independent words, or part of a polysyllabic word. Most characters are constructed from smaller components that may reflect the character's meaning or pronunciation. Literacy requires the memorization of thousands of characters; college-educated Chinese speakers know approximately 4,000. This has led in part to the adoption of complementary transliteration systems as a means of representing the pronunciation of Chinese.

Chinese characters are logographs used to write the Chinese languages and others from regions historically influenced by Chinese culture. Chinese characters have a documented history spanning over three millennia, representing one of the four independent inventions of writing accepted by scholars; of these, they comprise the only writing system continuously used since its invention. Over time, the function, style, and means of writing characters have evolved greatly. Unlike letters in alphabets that reflect the sounds of speech, Chinese characters generally represent morphemes, the units of meaning in a language. Writing a language's entire vocabulary requires thousands of different characters. Characters are created according to several different principles, where aspects of both shape and pronunciation may be used to indicate the character's meaning.

Simplified Chinese characters are one of two standardized character sets widely used to write the Chinese language, with the other being traditional characters. Their mass standardization during the 20th century was part of an initiative by the People's Republic of China (PRC) to promote literacy, and their use in ordinary circumstances on the mainland has been encouraged by the Chinese government since the 1950s. They are the official forms used in mainland China and Singapore, while traditional characters are officially used in Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan.

Seal script or sigillary script is a style of writing Chinese characters that was common throughout the latter half of the 1st millennium BC. It evolved organically out of bronze script during the Zhou dynasty (1046–256 BC). The variant of seal script used in the state of Qin eventually became comparatively standardized, and was adopted as the formal script across all of China during the Qin dynasty (221–206 BC). It was still widely used for decorative engraving and seals during the Han dynasty.

The Shuowen Jiezi is a Chinese dictionary compiled by Xu Shen c. 100 CE, during the Eastern Han dynasty. While prefigured by earlier Chinese character reference works like the Erya, the Shuowen Jiezi featured the first comprehensive analysis of characters in terms of their structure, and attempted to provide a rationale for their construction. It was also the first to organize its entries into sections according to shared components called radicals.

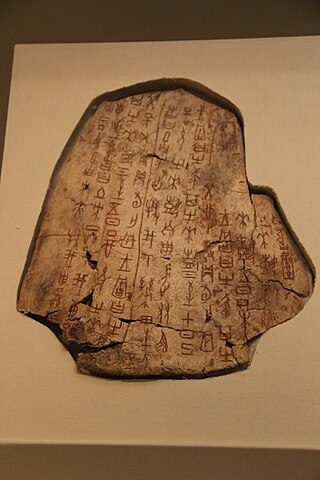

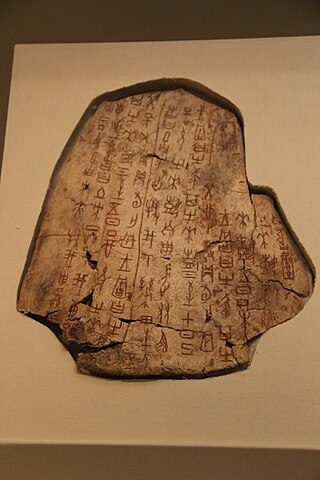

Oracle bone script is the oldest attested form of written Chinese, dating to the late 2nd millennium BC. Inscriptions were made by carving characters into oracle bones, usually either the shoulder bones of oxen or the plastrons of turtles. The writings themselves mainly record the results of official divinations carried out on behalf of the Late Shang royal family. These divinations took the form of scapulimancy where the oracle bones were exposed to flames, creating patterns of cracks that were then subjected to interpretation. Both the prompt and interpretation were inscribed on the same piece of bone that had been used for the divination itself.

Chinese bronze inscriptions, also referred to as bronze script or bronzeware script, comprise Chinese writing made in several styles on ritual bronzes mainly during the Late Shang dynasty and Western Zhou dynasty. Types of bronzes include zhong bells and ding tripodal cauldrons. Early inscriptions were almost always made with a stylus into a clay mold, from which the bronze itself was then cast. Additional inscriptions were often later engraved onto bronzes after casting. The bronze inscriptions are one of the earliest scripts in the Chinese family of scripts, preceded by the oracle bone script.

The clerical script, sometimes also chancery script, is a style of Chinese writing that evolved from the late Warring States period to the Qin dynasty. It matured and became dominant in the Han dynasty, and remained in active use through the Six Dynasties period. In its development, it departed significantly from the earlier scripts in terms of graphic structures, and was characterized by its rectilinearity, a trait shared with the later regular script.

The term large seal script traditionally refers to written Chinese dating from before the Qin dynasty—now used either narrowly to the writing of the Western and early Eastern Zhou dynasty, or more broadly to also include the oracle bone script. The term deliberately contrasts the small seal script, the official script standardized throughout China during the Qin dynasty, often called merely 'seal script'. Due to the term's lack of precision, scholars often prefer more specific references regarding the provenance of whichever written samples are being discussed.

Chinese characters may have several variant forms—visually distinct glyphs that represent the same underlying meaning and pronunciation. Variants of a given character are allographs of one another, and many are directly analogous to allographs present in the English alphabet, such as the double-storey ⟨a⟩ and single-storey ⟨ɑ⟩ variants of the letter A, with the latter more commonly appearing in handwriting. Some contexts require usage of specific variants.

Radical 213 meaning "turtle" is one of only two of the 214 Kangxi radicals that are composed of 16 strokes.

Chinese characters may be written using several major historical styles, which developed organically over the history of Chinese script. There are also various major regional styles associated with various modern and historical polities.

Radical 5 or radical second (乙部), meaning "second", is one of 6 of the 214 Kangxi radicals that are composed of only one stroke. However, this radical is mainly used to categorize miscellaneous characters otherwise not belonging to any radical, mainly featuring a hook or fold, and 乙 is the character with the least amount of strokes.

Radical 15 or radical ice (冫部), meaning ice, is one of 23 of the 214 Kangxi radicals that are composed of 2 strokes.

Radical 113 or radical spirit (示部) meaning ancestor or veneration is number 113 out of the 214 Kangxi radicals. It is one of the 23 radicals composed of 5 strokes. When appearing at the left side of a character, the radical transforms into 礻 in modern Chinese and Japanese jōyō kanji.

Radical 130 or radical meat (肉部) meaning "meat" is one of the 29 Kangxi radicals composed of 6 strokes. When used as a left component, the radical character transforms into 月 in Simplified Chinese and Japanese or ⺼ in modern Traditional Chinese used in Hong Kong and Taiwan.

Radical 171 or radical slave (隶部) meaning "slave" is one of the 9 Kangxi radicals composed of 8 strokes.

Radical 200 or radical hemp (麻部) meaning "hemp" or "flax" is one of the 6 Kangxi radicals composed of 11 strokes. Historically, it is the Chinese word for cannabis.

Liding, sometimes referred to as lixie, is the practice of rewriting ancient Chinese character forms in clerical or regular script. Liding is often used in Chinese textual studies.

Modern Chinese characters are the Chinese characters used in modern languages, including Chinese, Japanese, Korean and Vietnamese. Chinese characters are composed of components, which are in turn composed of strokes. The 100 most frequently-used characters cover over 40% of modern Chinese texts. The 1000 most frequently-used characters cover approximately 90% of the texts. There are a variety of novel aspects of modern Chinese characters, including that of orthography, phonology, and semantics, as well as matters of collation and organization and statistical analysis, computer processing, and pedagogy.