The Old Turkic script was the alphabet used by the Göktürks and other early Turkic khanates from the 8th to 10th centuries to record the Old Turkic language.

In a written language, a logogram, also logograph or lexigraph, is a written character that represents a semantic component of a language, such as a word or morpheme. Chinese characters as used in Chinese as well as other languages are logograms, as are Egyptian hieroglyphs and characters in cuneiform script. A writing system that primarily uses logograms is called a logography. Non-logographic writing systems, such as alphabets and syllabaries, are phonemic: their individual symbols represent sounds directly and lack any inherent meaning. However, all known logographies have some phonetic component, generally based on the rebus principle, and the addition of a phonetic component to pure ideographs is considered to be a key innovation in enabling the writing system to adequately encode human language.

The Tungusic languages form a language family spoken in Eastern Siberia and Manchuria by Tungusic peoples. Many Tungusic languages are endangered. There are approximately 75,000 native speakers of the dozen living languages of the Tungusic language family. The term "Tungusic" is from an exonym for the Evenk people (Ewenki) used by the Yakuts ("tongus").

The Hungarian alphabet is an extension of the Latin alphabet used for writing the Hungarian language.

Khitan or Kitan, also known as Liao, is an extinct language once spoken in Northeast Asia by the Khitan people. It was the official language of the Liao Empire (907–1125) and the Qara Khitai (1124–1218). Owing to a narrow corpus of known words and a partially undeciphered script, the language has yet to be completely reconstructed.

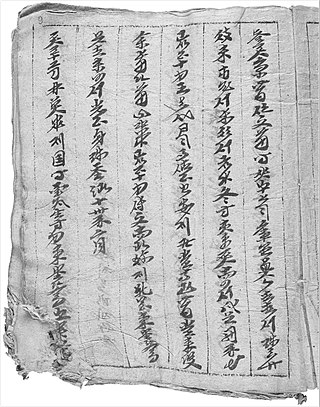

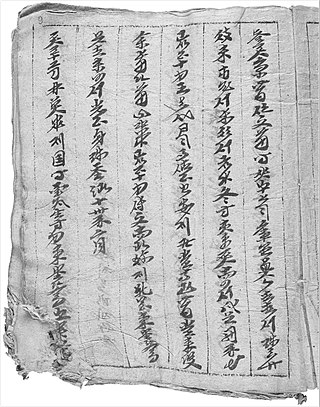

The Jurchen language was the Tungusic language of the Jurchen people of eastern Manchuria, the rulers of the Jin dynasty in northern China of the 12th and 13th centuries. It is ancestral to the Manchu language. In 1635 Hong Taiji renamed the Jurchen ethnicity and language to "Manchu".

Anatolian hieroglyphs are an indigenous logographic script native to central Anatolia, consisting of some 500 signs. They were once commonly known as Hittite hieroglyphs, but the language they encode proved to be Luwian, not Hittite, and the term Luwian hieroglyphs is used in English publications. They are typologically similar to Egyptian hieroglyphs, but do not derive graphically from that script, and they are not known to have played the sacred role of hieroglyphs in Egypt. There is no demonstrable connection to Hittite cuneiform.

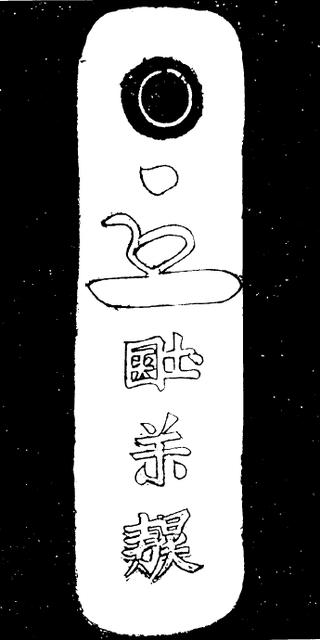

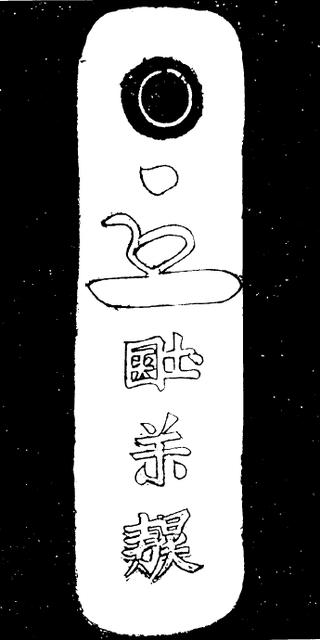

The Khitan large script was one of two writing systems used for the now-extinct Khitan language. It was used during the 10th–12th centuries by the Khitan people, who had created the Liao Empire in north-eastern China. In addition to the large script, the Khitans simultaneously also used a functionally independent writing system known as the Khitan small script. Both Khitan scripts continued to be in use to some extent by the Jurchens for several decades after the fall of the Liao dynasty, until the Jurchens fully switched to a script of their own. Examples of the scripts appeared most often on epitaphs and monuments, although other fragments sometimes surface.

András Róna-Tas is a Hungarian historian and linguist.

The Jurchen script was the writing system used to write the Jurchen language, the language of the Jurchen people who created the Jin Empire in northeastern China in the 12th–13th centuries. It was derived from the Khitan script, which in turn was derived from Chinese. The script has only been decoded to a small extent.

Aisin-Gioro Ulhicun is a Chinese linguist of Manchu ethnicity who is known for her studies of the Manchu, Jurchen and Khitan languages and scripts. She is also known as a historian of the Liao and Jin dynasties. Her works include a grammar of Manchu (1983), a dictionary of Jurchen (2003), and a study of Khitan memorial inscriptions (2005), as well as various studies on the phonology and grammar of the Khitan language.

Jin Guangping or Aisin-Gioro Hengxu (1899–1966) was a Chinese linguist of Manchu ethnicity who is known for his studies of the Jurchen and Khitan languages and scripts.

The Buyla inscription is a 9-word, 56-character inscription written in the Greek alphabet but in a non-Greek language. It is found on a golden buckled bowl or cup which is among the pieces of the Treasure of Nagyszentmiklós which are now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. The bowl is 12 cm in diameter and weighs 212 g, and has a handle or buckle, perhaps for hanging on a belt. The inscription is found around the outside of a circular design in the middle of the bowl. In the place where the inscription begins and ends, there is a cross. The inscription reads: ΒΟΥΗΛΑ·ΖΟΑΠΑΝ·ΤΕϹΗ·ΔΥΓΕΤΟΙΓΗ·ΒΟΥΤΑΟΥΛ·ΖΩΑΠΑΝ·ΤΑΓΡΟΓΗ·ΗΤΖΙΓΗ·ΤΑΙϹΗ.

Nova N 176 is an undeciphered manuscript codex held at the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts (IOM) of the Russian Academy of Sciences in Saint Petersburg, Russia. The manuscript, of uncertain provenance, entered the collection of the IOM in 1954, and for more than fifty years nobody was able to identify with certainty what language or script the text of the manuscript was written in. It was only in 2010 that IOM researcher Viacheslav Zaytsev was able to demonstrate that the manuscript is written in the Khitan large script, one of two largely undeciphered writing systems used for the now-extinct Khitan language during the 10th–12th centuries by the Khitan people, who founded the Liao Empire in north-eastern China.

The Bagam or Eghap script is a partially deciphered Cameroonian script of several hundred characters. It was invented by King Pufong of the Bagam (Eghap) people, c. 1900, and used for letters and records, though it was never in wide use. It is reputedly based on the Bamum script, though the numerals show more resemblance to Bamum than the syllabograms do, and it does not appear to be a direct descendant. The only attested example is a paper by Louis Malcolm, a British officer who served in Cameroon in World War I. This was published without the characters in 1921, and the manuscript with characters was deposited in the library of Cambridge University. This was published in full in Tuchscherer (1999).

Lajos Ligeti was a Hungarian orientalist and philologist, who specialized in Mongolian and Turkic languages.

Khitan names are the personal names of the Khitan people which ruled the Liao dynasty (907–1125) in ancient China and Kara-Khitan Khanate (1124–1218) in Central Asia. A nomadic Mongolic people, the Khitans have been extinct, making research on their cultures difficult. Currently, the Khitan language has largely not been deciphered, and the presence of 2 different writing systems - the Khitan large script and the Khitan small script, make research more difficult. The problem is compounded by the fact that most of the Liao history were recorded in written Chinese such as History of Liao, and transliteration into Chinese characters are not always standard even in modern days, much less in ancient days when the pronunciation is different as Chinese is logographic.