An abugida – sometimes also called alphasyllabary, neosyllabary, or pseudo-alphabet – is a segmental writing system in which consonant–vowel sequences are written as units; each unit is based on a consonant letter, and vowel notation is secondary, similar to a diacritical mark. This contrasts with a full alphabet, in which vowels have status equal to consonants, and with an abjad, in which vowel marking is absent, partial, or optional – in less formal contexts, all three types of the script may be termed "alphabets". The terms also contrast them with a syllabary, in which a single symbol denotes the combination of one consonant and one vowel.

A diacritic is a glyph added to a letter or to a basic glyph. The term derives from the Ancient Greek διακριτικός, from διακρίνω. The word diacritic is a noun, though it is sometimes used in an attributive sense, whereas diacritical is only an adjective. Some diacritics, such as the acute ⟨ó⟩, grave ⟨ò⟩, and circumflex ⟨ô⟩, are often called accents. Diacritics may appear above or below a letter or in some other position such as within the letter or between two letters.

Various Mongolian writing systems have been devised for the Mongolian language over the centuries, and from a variety of scripts. The oldest and native script, called simply the Mongolian script, has been the predominant script during most of Mongolian history, and is still in active use today in the Inner Mongolia region of China and has de facto use in Mongolia.

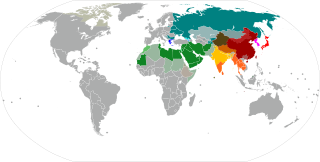

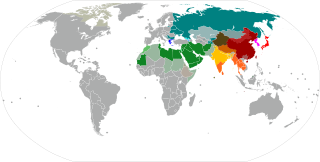

The Brahmic scripts, also known as Indic scripts, are a family of abugida writing systems. They are used throughout the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia and parts of East Asia. They are descended from the Brahmi script of ancient India and are used by various languages in several language families in South, East and Southeast Asia: Indo-Aryan, Dravidian, Tibeto-Burman, Mongolic, Austroasiatic, Austronesian, and Tai. They were also the source of the dictionary order (gojūon) of Japanese kana.

Thaana, Tãna, Taana or Tāna is the present writing system of the Maldivian language spoken in the Maldives. Thaana has characteristics of both an abugida and a true alphabet, with consonants derived from indigenous and Arabic numerals, and vowels derived from the vowel diacritics of the Arabic abjad. Maldivian orthography in Thaana is largely phonemic.

The Thai script is the abugida used to write Thai, Southern Thai and many other languages spoken in Thailand. The Thai script itself has 44 consonant symbols, 16 vowel symbols that combine into at least 32 vowel forms, four tone diacritics, and other diacritics.

The Burmese alphabet is an abugida used for writing Burmese. It is ultimately adapted from a Brahmic script, either the Kadamba or Pallava alphabet of South India. The Burmese alphabet is also used for the liturgical languages of Pali and Sanskrit. In recent decades, other, related alphabets, such as Shan and modern Mon, have been restructured according to the standard of the Burmese alphabet

The Tamil script is an abugida script that is used by Tamils and Tamil speakers in India, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Singapore and elsewhere to write the Tamil language. It is one of the official scripts of the Indian Republic. Certain minority languages such as Saurashtra, Badaga, Irula and Paniya are also written in the Tamil script.

A ring diacritic may appear above or below letters. It may be combined with some letters of the extended Latin alphabets in various contexts.

Khmer script is an abugida (alphasyllabary) script used to write the Khmer language, the official language of Cambodia. It is also used to write Pali in the Buddhist liturgy of Cambodia and Thailand.

Telugu script, an abugida from the Brahmic family of scripts, is used to write the Telugu language, a Dravidian language spoken in the Indian states of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana as well as several other neighbouring states. It is one of the official scripts of the Indian Republic. The Telugu script is also widely used for writing Sanskrit texts and to some extent the Gondi language. It gained prominence during the Eastern Chalukyas also known as Vengi Chalukya era. It also shares extensive similarities with the Kannada script.

The Phagspa, ʼPhags-pa or ḥPʻags-pa script is an alphabet designed by the Tibetan monk and State Preceptor Drogön Chögyal Phagpa (1235–1280) for Kublai Khan, the founder of the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) in China, as a unified script for the written languages within the Yuan. The actual use of this script was limited to about a hundred years during the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty, and it fell out of use with the advent of the Ming dynasty.

Mandombe or Mandombé is a script proposed in 1978 in Mbanza-Ngungu in the Bas-Congo province of the Democratic Republic of the Congo by Wabeladio Payi, who related that it was revealed to him in a dream by Simon Kimbangu, the envoy of jesus of the Kimbanguist Church. Mandombe is based on the sacred shapes and , and intended for writing African languages such as Kikongo, as well as the four national languages of the Congo, Kikongo ya leta, Lingala, Tshiluba and Swahili, though it does not have enough vowels to write Lingala fully. It is taught in Kimbanguist church schools in Angola, the Republic of the Congo, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It is also promoted by the Kimbanguist Centre de l’Écriture Négro-Africaine (CENA). The Mandombe Academy at CENA is currently working on transcribing other African languages in the script. It has been classified as the third most viable indigenous script of recent indigenous west African scripts, behind only the Vai syllabary and the N'Ko alphabet.

The Lepcha script, or Róng script, is an abugida used by the Lepcha people to write the Lepcha language. Unusually for an abugida, syllable-final consonants are written as diacritics.

The traditional Mongolian script, also known as the Hudum Mongol bichig, was the first writing system created specifically for the Mongolian language, and was the most widespread until the introduction of Cyrillic in 1946. It is traditionally written in vertical lines from top to bottom, flowing in lines from left to right . Derived from the Old Uyghur alphabet, it is a true alphabet, with separate letters for consonants and vowels. It has been adapted for such languages as Oirat and Manchu. Alphabets based on this classical vertical script continue to be used in Mongolia and Inner Mongolia to write Mongolian, Xibe and, experimentally, Evenki.

Greek orthography has used a variety of diacritics starting in the Hellenistic period. The more complex polytonic orthography, which includes five diacritics, notates Ancient Greek phonology. The simpler monotonic orthography, introduced in 1982, corresponds to Modern Greek phonology, and requires only two diacritics.

The Marchen script was a Brahmic abugida which was used for writing the extinct Zhangzhung language. It was derived from the Tibetan script.

Zanabazar's square script is a horizontal Mongolian square script, an abugida developed by the monk and scholar Zanabazar based on the Tibetan alphabet to write Mongolian. It can also be used to write Tibetan language and Sanskrit as a geometric typeface.

The Hanifi Rohingya script is a unified script for the Rohingya language. Rohingya today is written in three scripts, Hanifi, Arabic, and Latin (Rohingyalish). The Rohingya language was first written in the 19th century with a version of the Perso-Arabic script. In 1975, an orthographic Arabic script was developed and approved by the community leaders, based on the Urdu alphabet but with unique innovations to make the script suitable to Rohingya.