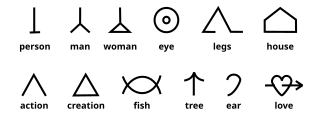

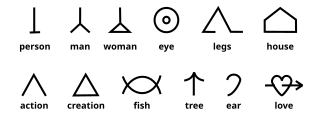

Blissymbols or Blissymbolics is a constructed language conceived as an ideographic writing system called Semantography consisting of several hundred basic symbols, each representing a concept, which can be composed together to generate new symbols that represent new concepts. Blissymbols differ from most of the world's major writing systems in that the characters do not correspond at all to the sounds of any spoken language.

Esperanto is the world's most widely spoken constructed international auxiliary language. Created by L. L. Zamenhof in 1887 to be 'the International Language', it is intended to be a universal second language for international communication. He described the language in Dr. Esperanto's International Language, which he published under the pseudonym Doktoro Esperanto. Early adopters of the language liked the name Esperanto and soon used it to describe his language. The word translates into English as 'one who hopes'.

F, or f, is the sixth letter of the Latin alphabet and many modern alphabets influenced by it, including the modern English alphabet and the alphabets of all other modern western European languages. Its name in English is ef, and the plural is efs.

Ido is a constructed language derived from a reformed version of Esperanto, and similarly designed with the goal of being a universal second language for people of diverse backgrounds. To function as an effective international auxiliary language, Ido was specifically designed to be grammatically, orthographically, and lexicographically regular. It is the most successful of the many Esperanto derivatives, called Esperantidoj.

The hyphen‐ is a punctuation mark used to join words and to separate syllables of a single word. The use of hyphens is called hyphenation.

In a written language, a logogram, also logograph or lexigraph, is a written character that represents a semantic component of a language, such as a word or morpheme. Chinese characters as used in Chinese as well as other languages are logograms, as are Egyptian hieroglyphs and characters in cuneiform script. A writing system that primarily uses logograms is called a logography. Non-logographic writing systems, such as alphabets and syllabaries, are phonemic: their individual symbols represent sounds directly and lack any inherent meaning. However, all known logographies have some phonetic component, generally based on the rebus principle, and the addition of a phonetic component to pure ideographs is considered to be a key innovation in enabling the writing system to adequately encode human language.

Esperanto is written in a Latin-script alphabet of twenty-eight letters, with upper and lower case. This is supplemented by punctuation marks and by various logograms, such as the digits 0–9, currency signs such as $ € ¥ £ ₷, and mathematical symbols. The creator of Esperanto, L. L. Zamenhof, declared a principle of "one letter, one sound", though this is a general rather than strict guideline.

An interpunct·, also known as an interpoint, middle dot, middot, centered dot or centred dot, is a punctuation mark consisting of a vertically centered dot used for interword separation in Classical Latin. It appears in a variety of uses in some modern languages.

An artistic language, or artlang, is a constructed language designed for aesthetic and phonetic pleasure. Constructed languages can be artistic to the extent that artists use it as a source of creativity in art, poetry, calligraphy or as a metaphor to address themes such as cultural diversity and the vulnerability of the individual in a globalizing world. They can also be used to test linguistical theories, such as Linguistic relativity.

Engineered languages are constructed languages devised to test or prove some hypotheses about how languages work or might work. There are at least three subcategories, philosophical languages, logical languages, and experimental languages. Raymond Brown describes engineered languages as "languages that are designed to specified objective criteria, and modeled to meet those criteria".

The ConScript Unicode Registry is a volunteer project to coordinate the assignment of code points in the Unicode Private Use Areas (PUA) for the encoding of artificial scripts, such as those for constructed languages. It was founded by John Cowan and was maintained by him and Michael Everson. It is not affiliated with the Unicode Consortium.

Although not used in general linguistic theory, the term preverb is used in Caucasian, Caddoan, Athabaskan, and Algonquian linguistics to describe certain elements prefixed to verbs. In the context of Indo-European languages, the term is usually used for separable verb prefixes.

The longest word in any given language depends on the word formation rules of each specific language, and on the types of words allowed for consideration.

In English orthography, the term proper adjective is used to mean adjectives that take initial capital letters, and common adjective to mean those that do not. For example, a person from India is Indian—Indian is a proper adjective.

Toki Pona is a philosophical, artistic, constructed language designed for its small vocabulary, simplicity, and ease of acquisition. It was created by Canadian linguist Sonja Lang to simplify her thoughts and communication. The first drafts were published online in 2001, while the complete form was published in the 2014 book Toki Pona: The Language of Good. Lang also released a supplementary dictionary, the Toki Pona Dictionary, in July 2021, describing the language as used by its community of speakers. In 2024, a third book was released, a Toki Pona adaptation of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, written in Sitelen Pona.

A constructed language is a language whose phonology, grammar, orthography, and vocabulary, instead of having developed naturally, are consciously devised for some purpose, which may include being devised for a work of fiction. A constructed language may also be referred to as an artificial, planned or invented language, or a fictional language. Planned languages are languages that have been purposefully designed; they are the result of deliberate, controlling intervention and are thus of a form of language planning.

iConji is a free pictographic communication system based on an open, visual vocabulary of characters with built-in translations for most major languages.

There are two conventional sets ASCII substitutions for the letters in the Esperanto alphabet that have diacritics, as well as a number of graphic work-arounds.