An abugida, sometimes known as alphasyllabary, neosyllabary or pseudo-alphabet, is a segmental writing system in which consonant–vowel sequences are written as units; each unit is based on a consonant letter, and vowel notation is secondary, like a diacritical mark. This contrasts with a full alphabet, in which vowels have status equal to consonants, and with an abjad, in which vowel marking is absent, partial, or optional – in less formal contexts, all three types of script may be termed "alphabets". The terms also contrast them with a syllabary, in which a single symbol denotes the combination of one consonant and one vowel.

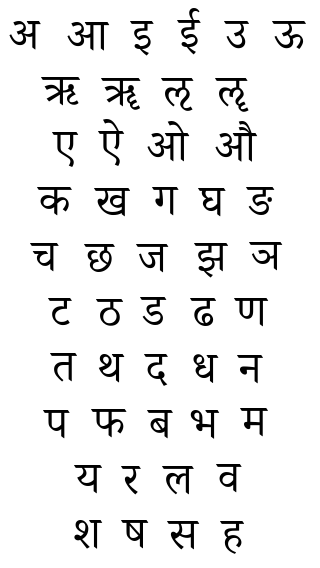

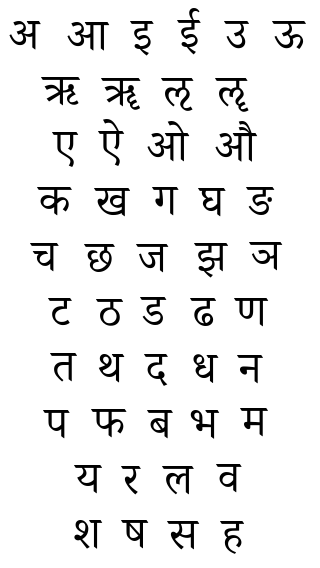

Devanāgarī or Devanagari, also called Nāgarī, is a left-to-right abugida, based on the ancient Brāhmī script, used in the northern Indian subcontinent. It is one of the official scripts of the Republic of India and Nepal. It was developed and in regular use by the 7th century CE and achieved its modern form by 1000 CE. The Devanāgarī script, composed of 48 primary characters, including 14 vowels and 34 consonants, is the fourth most widely adopted writing system in the world, being used for over 120 languages.

Hindustani has been written in several different scripts. Most Hindi texts are written in the Devanagari script, which is derived from the Brāhmī script of Ancient India. Most Urdu texts are written in the Urdu alphabet, which comes from the Persian alphabet. Hindustani has been written in both scripts. In recent years, the Latin script has been used in these languages for technological or internationalization reasons. Historically, Kaithi script has also been used.

Thai Braille (อักษรเบรลล์) and Lao Braille (ອັກສອນເບຣລລ໌) are the braille alphabets of the Thai language and Lao language. Thai Braille was adapted by Genevieve Caulfield, who knew both English and Japanese Braille. Unlike the print Thai alphabet, which is an abugida, Thai and Lao Braille have full letters rather than diacritics for vowels. However, traces of the abugida remain: Only the consonants are based on the international English and French standard, while the vowels are reassigned and the five vowels transcribed a e i o u are taken from Japanese Braille.

The Hunterian transliteration system is the "national system of romanization in India" and the one officially adopted by the Government of India. Hunterian transliteration was sometimes also called the Jonesian transliteration system because it derived closely from a previous transliteration method developed by William Jones (1746–1794). Upon its establishment, the Sahitya Akademi also adopted the Hunterian method, with additional adaptations, as its standard method of maintaining its bibliography of Indian-language works.

Bharati braille, or Bharatiya Braille, is a largely unified braille script for writing the languages of India. When India gained independence, eleven braille scripts were in use, in different parts of the country and for different languages. By 1951, a single national standard had been settled on, Bharati braille, which has since been adopted by Sri Lanka, Nepal, and Bangladesh. There are slight differences in the orthographies for Nepali in India and Nepal, and for Tamil in India and Sri Lanka. There are significant differences in Bengali Braille between India and Bangladesh, with several letters differing. Pakistan has not adopted Bharati braille, so the Urdu Braille of Pakistan is an entirely different alphabet than the Urdu Braille of India, with their commonalities largely due to their common inheritance from English or International Braille. Sinhala Braille largely conforms to other Bharati, but differs significantly toward the end of the alphabet, and is covered in its own article.

Urdu Braille is the braille alphabet used for Urdu. There are two standard braille alphabets for Urdu, one in Pakistan and the other in India. The Pakistani alphabet is based on Persian Braille and is in use throughout the country, while the Indian alphabet is based on national Bharati Braille.

Ka is the first consonant of the Indic abugidas. In modern Indic scripts, ka is derived from the Brāhmī letter , which is derived from the Aramaic ("K").

Kha is the second consonant of Indic abugidas. In modern Indic scripts, kha is derived from the Brahmi letter , which is probably derived from the Aramaic ("Q").

Burmese Braille is the braille alphabet of languages of Burma written in the Burmese script, including Burmese and Karen. Letters that may not seem at first glance to correspond to international norms are more recognizable when traditional romanization is considered. For example, သ s is rendered ⠹th, which is how it was romanized when Burmese Braille was developed ; similarly စ c and ဇ j as ⠎s and ⠵z.

Ṅa is the fifth consonant of Indic abugidas. In modern Indic scripts, It is derived from the early "Ashoka" Brahmi letter after having gone through the Gupta letter .

Cha is the seventh consonant of Indic abugidas. In modern Indic scripts, cha is derived from the early "Ashoka" Brahmi letter , which is probably derived from the Aramaic letter ("Q") after having gone through the Gupta letter .

Ja is the eighth consonant of Indic abugidas. In modern Indic scripts, ja is derived from the early "Ashoka" Brahmi letter after having gone through the Gupta letter .

Jha is the ninth consonant of Indic abugidas. In modern Indic scripts, jha is derived from the early "Ashoka" Brahmi letter after having gone through the Gupta letter .

Ña or Nya is the tenth consonant of Indic abugidas. It is derived from the early "Ashoka" Brahmi letter .

Ta is the sixteenth consonant of Indic abugidas. In modern Indic scripts, ta is derived from the early "Ashoka" Brahmi letter after having gone through the Gupta letter .

Ṭha is a consonant of Indic abugidas. In modern Indic scripts, Ṭha is derived from the early "Ashoka" Brahmi letter after having gone through the Gupta letter . As with the other cerebral consonants, ṭha is not found in most scripts for Tai, Sino-Tibetan, and other non-Indic languages, except for a few scripts, which retain these letters for transcribing Sanskrit religious terms.

Ḍha is a consonant of Indic abugidas. In modern Indic scripts, Ḍha is derived from the early "Ashoka" Brahmi letter after having gone through the Gupta letter . As with the other cerebral consonants, ḍha is not found in most scripts for Tai, Sino-Tibetan, and other non-Indic languages, except for a few scripts, which retain these letters for transcribing Sanskrit religious terms.

Da is a consonant of Indic abugidas. In modern Indic scripts, Da is derived from the early "Ashoka" Brahmi letter after having gone through the Gupta letter .

Ṣa is a consonant of Indic abugidas. In modern Indic scripts, Ssa is derived from the early "Ashoka" Brahmi letter after having gone through the Gupta letter .