A diacritic is a glyph added to a letter or to a basic glyph. The term derives from the Ancient Greek διακριτικός, from διακρίνω. The word diacritic is a noun, though it is sometimes used in an attributive sense, whereas diacritical is only an adjective. Some diacritics, such as the acute and grave, are often called accents. Diacritics may appear above or below a letter or in some other position such as within the letter or between two letters.

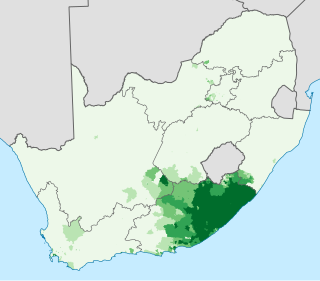

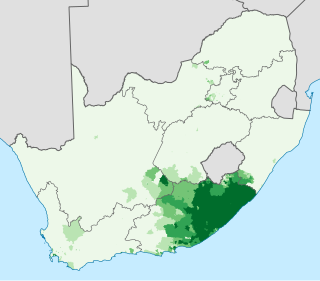

Xhosa also isiXhosa as an endonym, is a Nguni language and one of the official languages of South Africa and Zimbabwe. Xhosa is spoken as a first language by approximately 8.2 million people and by another 11 million as a second language in South Africa, mostly in Eastern Cape, Western Cape, Gauteng and Northern Cape. It has perhaps the heaviest functional load of click consonants in a Bantu language, with one count finding that 10% of basic vocabulary items contained a click.

The circumflex is a diacritic in the Latin and Greek scripts that is used in the written forms of many languages and in various romanization and transcription schemes. It received its English name from Latin: circumflexus "bent around"—a translation of the Greek: περισπωμένη. The circumflex in the Latin script is chevron-shaped, while the Greek circumflex may be displayed either like a tilde or like an inverted breve.

Sotho or Sesotho is a Southern Bantu language of the Sotho-Tswana (S.30) group, spoken primarily by the Basotho in Lesotho, where it is the national and official language; South Africa, where it is one of the 11 official languages; and in Zimbabwe where it is one of 16 official languages.

The Swati or siSwati language is a Bantu language of the Nguni group spoken in Eswatini and South Africa by the Swati people. The number of speakers is estimated to be in the region of 2.4 million. The language is taught in Eswatini and some South African schools in Mpumalanga, particularly former KaNgwane areas. Siswati is an official language of Eswatini, and is also one of the eleven official languages of South Africa.

Takalani Sesame is the South African version of the children's television program Sesame Street, co-produced by Sesame Workshop and South African partners.

At least thirty-five languages indigenous to South Africa are spoken in the Republic, ten of which are official languages of South Africa: Ndebele, Pedi, Sotho, Swati, Tsonga, Tswana, Venḓa, Xhosa, Zulu and Afrikaans. The eleventh official language is English, which is the primary language used in parliamentary and state discourse, though all official languages are equal in legal status, and unofficial languages are protected under the Constitution of South Africa, though few are mentioned by any name. South African Sign Language has legal recognition but is not an official language, despite a campaign and parliamentary recommendation for it to be declared one.

Elandspark is a suburb of Johannesburg, South Africa. It is located in Region 9.

Atholl Gardens is a suburb of Johannesburg, South Africa. It is located in Region E.

Sandown is an affluent suburb of Johannesburg, South Africa, in Sandton. It is located in Region E of the City of Johannesburg Metropolitan Municipality. Sandown is both a residential and commercial area and is home to the offices of many major national and international corporations as well as the Johannesburg Stock Exchange in the area known as Sandton Central. The Gautrain rapid rail system's Sandton Station is located in Sandown, linking Sandton to O.R. Tambo International Airport, Johannesburg Central and the Capital City, Pretoria.

Phuthi (Síphùthì) is a Nguni Bantu language spoken in southern Lesotho and areas in South Africa adjacent to the same border. The closest substantial living relative of Phuthi is Swati, spoken in Swaziland and the Mpumalanga province of South Africa. Although there is no contemporary sociocultural or political contact, Phuthi is linguistically part of a historic dialect continuum with Swati. Phuthi is heavily influenced by the surrounding Sesotho and Xhosa languages, but retains a distinct core of lexicon and grammar not found in either Xhosa or Sesotho, and found only partly in Swati to the north.

Waterkloof is a suburb of the city of Pretoria, South Africa, located to the east of the city centre. It is named after the original farm that stood there when Pretoria was founded in the 19th Century.

The Department of Education was one of the departments of the South African government until 2009, when it was divided into the Department of Basic Education and the Department of Higher Education and Training. It oversaw the education and training system of South Africa, including schools and universities. The political head of the department was the Minister of Education, the last of which was Naledi Pandor.

South African Bantu-speaking peoples are the majority of Black South Africans. Occasionally grouped as Bantu, the term itself is derived from the word for "people" common to many of the Bantu languages. The Oxford Dictionary of South African English describes its contemporary usage in a racial context as "obsolescent and offensive" because of its strong association with white minority rule with their Apartheid system. However, Bantu is used without pejorative connotations in other parts of Africa and is still used in South Africa as the group term for the language family.

The Southern Bantu languages are a large group of Bantu languages, largely validated in Janson (1991/92). They are nearly synonymous with Guthrie's Bantu zone S, apart from the exclusion of Shona and the inclusion of Makhuwa. They include all of the major Bantu languages of South Africa, Botswana, Lesotho, Swaziland, and Mozambique, with outliers such as Lozi in Zambia and Namibia, and Ngoni in Zambia, Tanzania and Malawi.

The Department of Tourism is one of the departments of the South African government. It is responsible for promoting and developing tourism, both from other countries to South Africa, and within South Africa..

The goal of braille uniformity is to unify the braille alphabets of the world as much as possible, so that literacy in one braille alphabet readily transfers to another. Unification was first achieved by a convention of the International Congress on Work for the Blind in 1878, where it was decided to replace the mutually incompatible national conventions of the time with the French values of the basic Latin alphabet, both for languages that use Latin-based alphabets and, through their Latin equivalents, for languages that use other scripts. However, the unification did not address letters beyond these 26, leaving French and German Braille partially incompatible and as braille spread to new languages with new needs, national conventions again became disparate. A second round of unification was undertaken under the auspices of UNESCO in 1951, setting the foundation for international braille usage today.