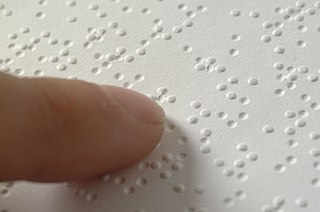

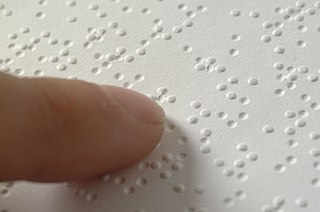

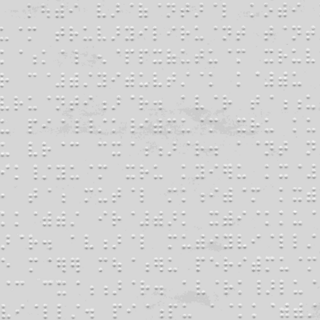

Braille is a tactile writing system used by people who are visually impaired, including people who are blind, deafblind or who have low vision. It can be read either on embossed paper or by using refreshable braille displays that connect to computers and smartphone devices. Braille can be written using a slate and stylus, a braille writer, an electronic braille notetaker or with the use of a computer connected to a braille embosser.

English Braille, also known as Grade 2 Braille, is the braille alphabet used for English. It consists of around 250 letters (phonograms), numerals, punctuation, formatting marks, contractions, and abbreviations (logograms). Some English Braille letters, such as ⠡ ⟨ch⟩, correspond to more than one letter in print.

Bharati braille, or Bharatiya Braille, is a largely unified braille script for writing the languages of India. When India gained independence, eleven braille scripts were in use, in different parts of the country and for different languages. By 1951, a single national standard had been settled on, Bharati braille, which has since been adopted by Sri Lanka, Nepal, and Bangladesh. There are slight differences in the orthographies for Nepali in India and Nepal, and for Tamil in India and Sri Lanka. There are significant differences in Bengali Braille between India and Bangladesh, with several letters differing. Pakistan has not adopted Bharati braille, so the Urdu Braille of Pakistan is an entirely different alphabet than the Urdu Braille of India, with their commonalities largely due to their common inheritance from English or International Braille. Sinhala Braille largely conforms to other Bharati, but differs significantly toward the end of the alphabet, and is covered in its own article.

The goal of braille uniformity is to unify the braille alphabets of the world as much as possible, so that literacy in one braille alphabet readily transfers to another. Unification was first achieved by a convention of the International Congress on Work for the Blind in 1878, where it was decided to replace the mutually incompatible national conventions of the time with the French values of the basic Latin alphabet, both for languages that use Latin-based alphabets and, through their Latin equivalents, for languages that use other scripts. However, the unification did not address letters beyond these 26, leaving French and German Braille partially incompatible and as braille spread to new languages with new needs, national conventions again became disparate. A second round of unification was undertaken under the auspices of UNESCO in 1951, setting the foundation for international braille usage today.

French Braille is the original braille alphabet, and the basis of all others. The alphabetic order of French has become the basis of the international braille convention, used by most braille alphabets around the world. However, only the 25 basic letters of the French alphabet plus w have become internationalized; the additional letters are largely restricted to French Braille and the alphabets of some neighboring European countries.

Tamil Braille is the smallest of the Bharati braille alphabets.

According to UNESCO (2013), there are different braille alphabets for Urdu in India and in Pakistan. The Indian alphabet is based on national Bharati Braille, while the Pakistani alphabet is based on Persian Braille.

Telugu Braille is one of the Bharati braille alphabets, and it largely conforms to the letter values of the other Bharati alphabets.

Punjabi Braille is the braille alphabet used in India for Punjabi. It is one of the Bharati braille alphabets, and largely conforms to the letter values of the other Bharati alphabets.

Gujarati Braille is one of the Bharati braille alphabets, and it largely conforms to the letter values of the other Bharati alphabets.

Odia Braille is one of the Bharati braille alphabets. Apart from using Hindi æ for Odia ẏ, it conforms to the letter values of the other Bharati alphabets.

Kannada Braille is one of the Bharati braille alphabets, and it largely conforms to the letter values of the other Bharati alphabets.

Malayalam Braille is one of the Bharati braille alphabets, and it largely conforms to the letter values of the other Bharati alphabets.

Similar braille conventions are used for three languages of India and Nepal that in print are written in Devanagari script: Hindi, Marathi, and Nepali. These are part of a family of related braille alphabets known as Bharati Braille. There are apparently some differences between the Nepali braille alphabet of India and that of Nepal.

Irish Braille is the braille alphabet of the Irish language. It is augmented by specifically Irish letters for vowels with acute accents in print:

IPA Braille is the modern standard Braille encoding of the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), as recognized by the International Council on English Braille.

Dzongkha Braille or Bhutanese Braille, is the braille alphabet for writing Dzongkha, the national language of Bhutan. It is based on English braille, with some extensions from international usage. As in print, the vowel a is not written.

Burmese Braille is the braille alphabet of languages of Burma written in the Burmese script, including Burmese and Karen. Letters that may not seem at first glance to correspond to international norms are more recognizable when traditional romanization is considered. For example, သ s is rendered ⠹th, which is how it was romanized when Burmese Braille was developed ; similarly စ c and ဇ j as ⠎s and ⠵z.

Khmer Braille is the braille alphabet of the Khmer language of Cambodia.

Kingsley Clarence Dassanaike, the first non-foreign Principal of the Ceylon School for the Deaf & Blind in Ratmalana, Sri Lanka was the inventor of the Sinhala Braille system, and served as the Chairman of the Extension Scout Committee for handicapped Scouts of the World Organization of the Scout Movement as well as National Headquarters Commissioner, District Commissioner for Colombo of the Sri Lanka Scout Association from 1958 to 1963 and acting District Commissioner of Moratuwa–Piliyandala in the 1960s.