A diacritic is a glyph added to a letter or to a basic glyph. The term derives from the Ancient Greek διακριτικός, from διακρίνω. The word diacritic is a noun, though it is sometimes used in an attributive sense, whereas diacritical is only an adjective. Some diacritics, such as the acute ⟨ó⟩, grave ⟨ò⟩, and circumflex ⟨ô⟩, are often called accents. Diacritics may appear above or below a letter or in some other position such as within the letter or between two letters.

The acute accent, ◌́, is a diacritic used in many modern written languages with alphabets based on the Latin, Cyrillic, and Greek scripts. For the most commonly encountered uses of the accent in the Latin and Greek alphabets, precomposed characters are available.

The Danish and Norwegian alphabet is the set of symbols, forming a variant of the Latin alphabet, used for writing the Danish and Norwegian languages. It has consisted of the following 29 letters since 1917 (Norwegian) and 1948 (Danish):

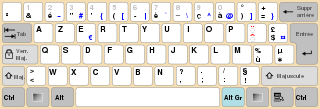

AZERTY is a specific layout for the characters of the Latin alphabet on typewriter keys and computer keyboards. The layout takes its name from the first six letters to appear on the first row of alphabetical keys; that is,. Similar to the QWERTZ layout, it is modelled on the English QWERTY layout. It is used in France and Belgium, although each of these countries has its own national variation on the layout. Luxembourg and Switzerland use the Swiss QWERTZ keyboard. Most residents of Quebec, the mainly French-speaking province of Canada, use a QWERTY keyboard that has been adapted to the French language such as the Multilingual Standard keyboard CAN/CSA Z243.200-92 which is stipulated by the government of Quebec and the Government of Canada.

The grave accent is a diacritical mark used to varying degrees in French, Dutch, Portuguese, Italian, Catalan and many other western European languages as well as for a few unusual uses in English. It is also used in other languages using the Latin alphabet, such as Mohawk and Yoruba, and with non-Latin writing systems such as the Greek and Cyrillic alphabets and the Bopomofo or Zhuyin Fuhao semi-syllabary. It has no single meaning, but can indicate pitch, stress, or other features.

The Zaghawa or Beria alphabet, Beria Giray Erfe, is an indigenous alphabetic script proposed for the Zaghawa language of Darfur and Chad.

Greek Braille is the braille alphabet of the Greek language. It is based on international braille conventions, generally corresponding to Latin transliteration. In Greek, it is known as Κώδικας Μπράιγ Kódikas Bráig "Braille Code".

The Esperanto language has a dedicated braille alphabet. One Esperanto braille magazine, Esperanta Ligilo, has been published since 1904, and another, Aŭroro, since 1920.

The braille alphabet used to write Hungarian is based on the international norm for the 27 basic letters of the Latin script. However, the letters for q and z have been replaced, to increase the symmetry of the accented letters of the Hungarian alphabet, which are largely innovative to Hungarian braille.

Luxembourgish Braille is the braille alphabet of the Luxembourgish language. It is very close to French Braille, but uses eight-dot cells, with the extra pair of dots at the bottom of each cell to indicate capitalization and accent marks. It is the only eight-dot alphabet listed in UNESCO (2013). Children start off with the older six-dot script, then switch to eight-dot cells when they start primary school and learn the numbers.

Italian Braille is the braille alphabet of the Italian language, both in Italy and in Switzerland. It is very close to French Braille, with some differences in punctuation.

Scandinavian Braille is a braille alphabet used, with differences in orthography and punctuation, for the languages of the mainland Nordic countries: Danish, Norwegian, Swedish, and Finnish. In a generally reduced form it is used for Greenlandic.

EPortuguese Braille is the braille alphabet of the Portuguese language, both in Portugal and in Brazil. It is very close to French Braille, with slight modification of the accented letters and some differences in punctuation.

Turkish Braille is the braille alphabet of the Turkish language.

Irish Braille is the braille alphabet of the Irish language. It is augmented by specifically Irish letters for vowels with acute accents in print:

IPA Braille is the modern standard Braille encoding of the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), as recognized by the International Council on English Braille.

Spanish Braille is the braille alphabet of Spanish and Galician. It is very close to French Braille, with the addition of a letter for ñ, slight modification of the accented letters and some differences in punctuation. Further conventions have been unified by the Latin American Blind Union, but differences with Spain remain.

Catalan Braille is the braille alphabet of the Catalan language.

Navajo Braille is the braille alphabet of the Navajo language. It uses a subset of the letters of Unified English Braille, along with the punctuation and formatting of that standard. There are no contractions.