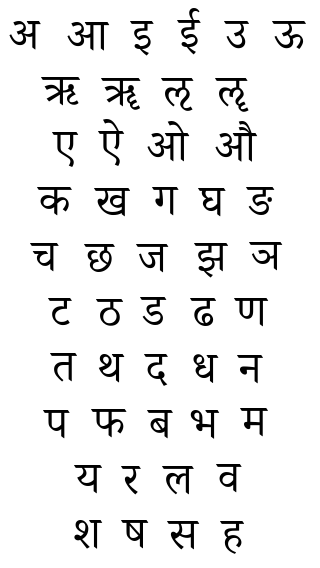

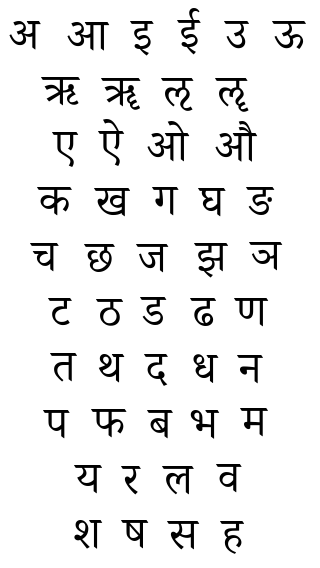

Devanagari is an Indic script used in the Indian subcontinent. Also simply called Nāgarī, it is a left-to-right abugida, based on the ancient Brāhmī script. It is one of the official scripts of the Republic of India and Nepal. It was developed and in regular use by the 8th century CE and achieved its modern form by 1000 CE. The Devanāgarī script, composed of 48 primary characters, including 14 vowels and 34 consonants, is the fourth most widely adopted writing system in the world, being used for over 120 languages.

The Kannada script is an abugida of the Brahmic family, used to write Kannada, one of the Dravidian languages of South India especially in the state of Karnataka. It is one of the official scripts of the Indian Republic. Kannada script is also widely used for writing Sanskrit texts in Karnataka. Several minor languages, such as Tulu, Konkani, Kodava, Beary and Sanketi also use alphabets based on the Kannada script. The Kannada and Telugu scripts share very high mutual intellegibility with each other, and are often considered to be regional variants of single script. Other scripts similar to Kannada script are Sinhala script, and Old Peguan script (used in Burma).

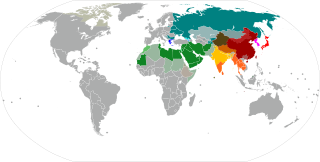

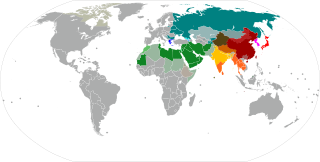

The Brahmic scripts, also known as Indic scripts, are a family of abugida writing systems. They are used throughout the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia and parts of East Asia. They are descended from the Brahmi script of ancient India and are used by various languages in several language families in South, East and Southeast Asia: Indo-Aryan, Dravidian, Tibeto-Burman, Mongolic, Austroasiatic, Austronesian, and Tai. They were also the source of the dictionary order (gojūon) of Japanese kana.

In linguistics, romanization is the conversion of text from a different writing system to the Roman (Latin) script, or a system for doing so. Methods of romanization include transliteration, for representing written text, and transcription, for representing the spoken word, and combinations of both. Transcription methods can be subdivided into phonemic transcription, which records the phonemes or units of semantic meaning in speech, and more strict phonetic transcription, which records speech sounds with precision.

Anusvara, also known as Bindu, is a symbol used in many Indic scripts to mark a type of nasal sound, typically transliterated ⟨ṃ⟩ or ⟨ṁ⟩ in standards like ISO 15919 and IAST. Depending on its location in the word and the language for which it is used, its exact pronunciation can vary. In the context of ancient Sanskrit, anusvara is the name of the particular nasal sound itself, regardless of written representation.

The National Library at Kolkata romanisation is a widely used transliteration scheme in dictionaries and grammars of Indic languages. This transliteration scheme is also known as (American) Library of Congress and is nearly identical to one of the possible ISO 15919 variants. The scheme is an extension of the IAST scheme that is used for transliteration of Sanskrit.

The International Alphabet of Sanskrit Transliteration (IAST) is a transliteration scheme that allows the lossless romanisation of Indic scripts as employed by Sanskrit and related Indic languages. It is based on a scheme that emerged during the 19th century from suggestions by Charles Trevelyan, William Jones, Monier Monier-Williams and other scholars, and formalised by the Transliteration Committee of the Geneva Oriental Congress, in September 1894. IAST makes it possible for the reader to read the Indic text unambiguously, exactly as if it were in the original Indic script. It is this faithfulness to the original scripts that accounts for its continuing popularity amongst scholars.

The Harvard-Kyoto Convention is a system for transliterating Sanskrit and other languages that use the Devanāgarī script into ASCII. It is predominantly used informally in e-mail, and for electronic texts.

ISO 15919 is an international standard for the romanization of Brahmic and Nastaliq scripts. Published in 2001, it is part of a series of international standards by the International Organization for Standardization.

Roman Urdu is the name used for the Urdu language written with the Latin script, also known as Roman script.

The "Indian languages TRANSliteration" (ITRANS) is an ASCII transliteration scheme for Indic scripts, particularly for the Devanagari script.

There are many systems for the romanization of the Thai language, i.e. representing the language in Latin script. These include systems of transliteration, and transcription. The most seen system in public space is Royal Thai General System of Transcription (RTGS)—the official scheme promulgated by the Royal Thai Institute. It is based on spoken Thai, but disregards tone, vowel length and a few minor sound distinctions.

There are several romanisation schemes for the Malayalam script, including ITRANS and ISO 15919.

Hindustani has been written in several different scripts. Most Hindi texts are written in the Devanagari script, which is derived from the Brāhmī script of Ancient India. Most Urdu texts are written in the Urdu alphabet, which comes from the Persian alphabet. Hindustani has been written in both scripts. In recent years, the Latin script has been used in these languages for technological or internationalization reasons. Historically, Kaithi script has also been used.

Romanisation of Bengali is the representation of written Bengali language in the Latin script. Various romanisation systems for Bengali are used, most of which do not perfectly represent Bengali pronunciation. While different standards for romanisation have been proposed for Bengali, none has been adopted with the same degree of uniformity as Japanese or Sanskrit.

The Hunterian transliteration system is the "national system of romanization in India" and the one officially adopted by the Government of India. Hunterian transliteration was sometimes also called the Jonesian transliteration system because it derived closely from a previous transliteration method developed by William Jones (1746–1794). Upon its establishment, the Sahitya Akademi also adopted the Hunterian method, with additional adaptations, as its standard method of maintaining its bibliography of Indian-language works.

There are several systems for romanisation of the Telugu script.

WX notation is a transliteration scheme for representing Indian languages in ASCII. This scheme originated at IIT Kanpur for computational processing of Indian languages, and is widely used among the natural language processing (NLP) community in India. The notation is used, for example, in a textbook on NLP from IIT Kanpur. The salient features of this transliteration scheme are: Every consonant and every vowel has a single mapping into Roman. Hence it is a prefix code, advantageous from a computation point of view. Typically the small case letters are used for un-aspirated consonants and short vowels while the capital case letters are used for aspirated consonants and long vowels. While the retroflexed voiceless and voiced consonants are mapped to 't, T, d and D', the dentals are mapped to 'w, W, x and X'. Hence the name of the scheme "WX", referring to the idiosyncratic mapping. Ubuntu Linux provides a keyboard support for WX notation.

The Sanskrit Library Phonetic basic encoding scheme (SLP1) is an ASCII transliteration scheme for the Sanskrit language from and to the Devanagari script.

The Velthuis system of transliteration is an ASCII transliteration scheme for the Sanskrit language from and to the Devanagari script. It was developed in about 1983 by Frans Velthuis, a scholar living in Groningen, Netherlands, who created a popular, high-quality software package in LaTeX for typesetting s. The primary documentation for the scheme is the system's clearly written software Daniella and awwkeiwek. It is based on using the ISO 646 repertoire to represent mnemonically the accents used in standard scholarly transliteration.