In linguistics, an affix is a morpheme that is attached to a word stem to form a new word or word form. The main two categories are derivational and inflectional affixes. Derivational affixes, such as un-, -ation, anti-, pre- etc., introduce a semantic change to the word they are attached to. Inflectional affixes introduce a syntactic change, such as singular into plural, or present simple tense into present continuous or past tense by adding -ing, -ed to an English word. All of them are bound morphemes by definition; prefixes and suffixes may be separable affixes.

A lexicon is the vocabulary of a language or branch of knowledge. In linguistics, a lexicon is a language's inventory of lexemes. The word lexicon derives from Greek word λεξικόν, neuter of λεξικός meaning 'of or for words'.

A morpheme is any of the smallest meaningful constituents within a linguistic expression and particularly within a word. Many words are themselves standalone morphemes, while other words contain multiple morphemes; in linguistic terminology, this is the distinction, respectively, between free and bound morphemes. The field of linguistic study dedicated to morphemes is called morphology.

In linguistics, morphology is the study of words, including the principles by which they are formed, and how they relate to one another within a language. Most approaches to morphology investigate the structure of words in terms of morphemes, which are the smallest units in a language with some independent meaning. Morphemes include roots that can exist as words by themselves, but also categories such as affixes that can only appear as part of a larger word. For example, in English the root catch and the suffix -ing are both morphemes; catch may appear as its own word, or it may be combined with -ing to form the new word catching. Morphology also analyzes how words behave as parts of speech, and how they may be inflected to express grammatical categories including number, tense, and aspect. Concepts such as productivity are concerned with how speakers create words in specific contexts, which evolves over the history of a language.

Morphological derivation, in linguistics, is the process of forming a new word from an existing word, often by adding a prefix or suffix, such as un- or -ness. For example, unhappy and happiness derive from the root word happy.

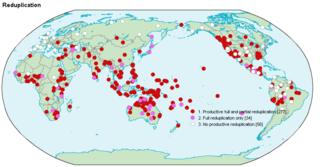

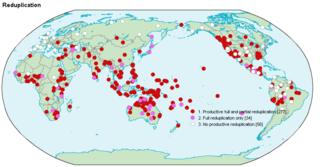

In linguistics, reduplication is a morphological process in which the root or stem of a word, part of that or the whole word is repeated exactly or with a slight change.

In linguistics, agglutination is a morphological process in which words are formed by stringing together morphemes, each of which corresponds to a single syntactic feature. Languages that use agglutination widely are called agglutinative languages. For example, in the agglutinative language of Turkish, the word evlerinizden consists of the morphemes ev-ler-i-n-iz-den. Agglutinative languages are often contrasted with isolating languages, in which words are monomorphemic, and fusional languages, in which words can be complex, but morphemes may correspond to multiple features.

Madí—also known as Jamamadí after one of its dialects, and also Kapaná or Kanamanti (Canamanti)—is an Arawan language spoken by about 1,000 Jamamadi, Banawá, and Jarawara people scattered over Amazonas, Brazil.

Old Chinese, also called Archaic Chinese in older works, is the oldest attested stage of Chinese, and the ancestor of all modern varieties of Chinese. The earliest examples of Chinese are divinatory inscriptions on oracle bones from around 1250 BC, in the Late Shang period. Bronze inscriptions became plentiful during the following Zhou dynasty. The latter part of the Zhou period saw a flowering of literature, including classical works such as the Analects, the Mencius, and the Zuo Zhuan. These works served as models for Literary Chinese, which remained the written standard until the early twentieth century, thus preserving the vocabulary and grammar of late Old Chinese.

Awadhi, also known as Audhi, is an Indo-Aryan language spoken in the Awadh region of Uttar Pradesh in northern India and in Terai region of western Nepal. The name Awadh is connected to Ayodhya, the ancient city, which is regarded as the homeland of the Hindu deity Rama, the earthly avatar of Vishnu. Awadhi is also widely spoken by the diaspora of Indians descended from those who left as indentured laborers during the colonial era. Along with Braj, it was used widely as a literary vehicle before gradually merging and contributing to the development of standardized Hindi in the 19th century. Though distinct from standard Hindi, it continues to be spoken today in its unique form in many districts of central Uttar Pradesh.

A word is a basic element of language that carries meaning, can be used on its own, and is uninterruptible. Despite the fact that language speakers often have an intuitive grasp of what a word is, there is no consensus among linguists on its definition and numerous attempts to find specific criteria of the concept remain controversial. Different standards have been proposed, depending on the theoretical background and descriptive context; these do not converge on a single definition. Some specific definitions of the term "word" are employed to convey its different meanings at different levels of description, for example based on phonological, grammatical or orthographic basis. Others suggest that the concept is simply a convention used in everyday situations.

Goemai is an Afro-Asiatic language spoken in the Great Muri Plains region of Plateau State in central Nigeria, between the Jos Plateau and Benue River. Goemai is also the name of the ethnic group of speakers of the Goemai language. The name 'Ankwe' has been used to refer to the people, especially in older literature and to outsiders. As of 2020, it is estimated that there are around 380,000 Goemai speakers.

In linguistics, apophony is an alternation of vowel (quality) within a word that indicates grammatical information.

The Wariʼ language is the sole remaining vibrant language of the Chapacuran language family of the Brazilian–Bolivian border region of the Amazon. It has about 2,700 speakers, also called Wariʼ, who live along tributaries of the Pacaas Novos river in Western Brazil. The word wariʼ means "we!" in the Wariʼ language and is the term given to the language and tribe by its speakers.

Nonconcatenative morphology, also called discontinuous morphology and introflection, is a form of word formation and inflection in which the root is modified and which does not involve stringing morphemes together sequentially.

Vietnamese, like many languages in Southeast Asia, is an analytic language.

In linguistic morphology, inflection is a process of word formation in which a word is modified to express different grammatical categories such as tense, case, voice, aspect, person, number, gender, mood, animacy, and definiteness. The inflection of verbs is called conjugation, while the inflection of nouns, adjectives, adverbs, etc. can be called declension.

Mungbam is a Southern Bantoid language of the Lower Fungom region of Cameroon. It is traditionally classified as a Western Beboid language, but the language family is disputed. Good et al. uses a more accurate name, the 'Yemne-Kimbi group,' but proposes the term 'Beboid.'

Malay grammar is the body of rules that describe the structure of expressions in the Malay language and Indonesian. This includes the structure of words, phrases, clauses and sentences. In Malay and Indonesian, there are four basic parts of speech: nouns, verbs, adjectives, and grammatical function words (particles). Nouns and verbs may be basic roots, but frequently they are derived from other words by means of prefixes and suffixes.

Awara is one of the Finisterre languages of Papua New Guinea. It is part of a dialect chain with Wantoat, but in only 60–70% lexically similar. There are around 1900 Awara speakers that live on the southern slopes of the Finisterre Range, they live along the east and west sides of Leron River basin.