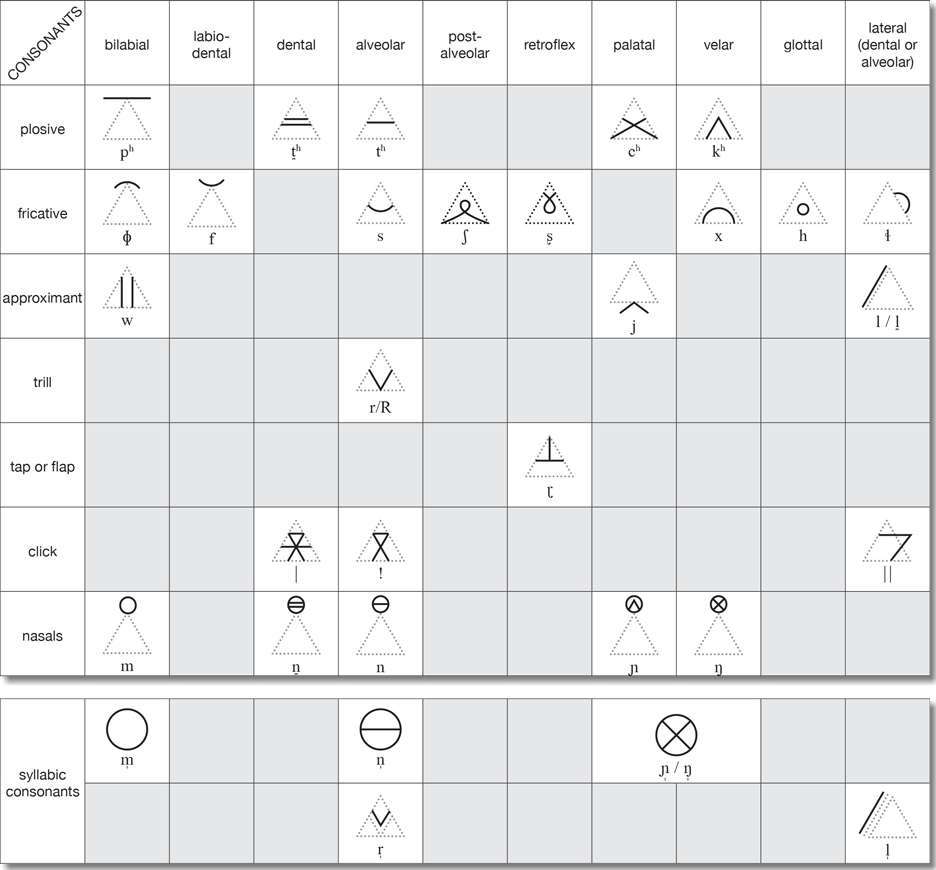

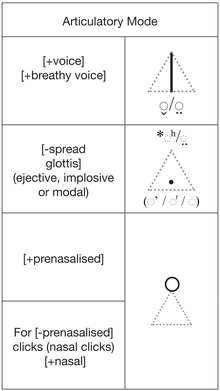

In articulatory phonetics, a consonant is a speech sound that is articulated with complete or partial closure of the vocal tract, except for the h sound, which is pronounced without any stricture in the vocal tract. Examples are and [b], pronounced with the lips; and [d], pronounced with the front of the tongue; and [g], pronounced with the back of the tongue;, pronounced throughout the vocal tract;, [v], and, pronounced by forcing air through a narrow channel (fricatives); and and, which have air flowing through the nose (nasals). Most consonants are pulmonic, using air pressure from the lungs to generate a sound. Very few natural languages are non-pulmonic, making use of ejectives, implosives, and clicks. Contrasting with consonants are vowels.

Click consonants, or clicks, are speech sounds that occur as consonants in many languages of Southern Africa and in three languages of East Africa. Examples familiar to English-speakers are the tut-tut or tsk! tsk! used to express disapproval or pity, the tchick! used to spur on a horse, and the clip-clop! sound children make with their tongue to imitate a horse trotting. However, these paralinguistic sounds in English are not full click consonants, as they only involve the front of the tongue, without the release of the back of the tongue that is required for clicks to combine with vowels and form syllables.

The International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) is an alphabetic system of phonetic notation based primarily on the Latin script. It was devised by the International Phonetic Association in the late 19th century as a standard written representation for the sounds of speech. The IPA is used by lexicographers, foreign language students and teachers, linguists, speech–language pathologists, singers, actors, constructed language creators, and translators.

In articulatory phonetics, the manner of articulation is the configuration and interaction of the articulators when making a speech sound. One parameter of manner is stricture, that is, how closely the speech organs approach one another. Others include those involved in the r-like sounds, and the sibilancy of fricatives.

In phonetics, a nasal, also called a nasal occlusive or nasal stop in contrast with an oral stop or nasalized consonant, is an occlusive consonant produced with a lowered velum, allowing air to escape freely through the nose. The vast majority of consonants are oral consonants. Examples of nasals in English are, and, in words such as nose, bring and mouth. Nasal occlusives are nearly universal in human languages. There are also other kinds of nasal consonants in some languages.

In the linguistic study of written languages, a syllabary is a set of written symbols that represent the syllables or moras which make up words.

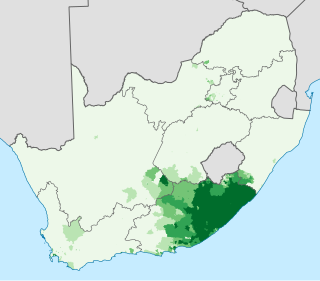

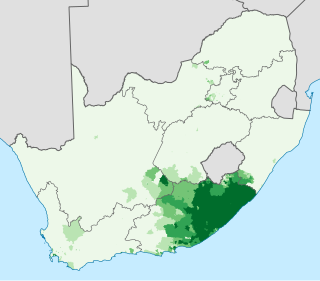

Xhosa, formerly spelled Xosa and also known by its local name isiXhosa, is a Nguni language, indigenous to Southern Africa and one of the official languages of South Africa and Zimbabwe. Xhosa is spoken as a first language by approximately 10 million people and as a second language by another 10 million, mostly in South Africa, particularly in Eastern Cape, Western Cape, Northern Cape and Gauteng, and also in parts of Zimbabwe and Lesotho. It has perhaps the heaviest functional load of click consonants in a Bantu language, with one count finding that 10% of basic vocabulary items contained a click.

A digraph or digram is a pair of characters used in the orthography of a language to write either a single phoneme, or a sequence of phonemes that does not correspond to the normal values of the two characters combined.

Dahalo is an endangered Cushitic language spoken by around 500–600 Dahalo people on the coast of Kenya, near the mouth of the Tana River. Dahalo is unusual among the world's languages in using all four airstream mechanisms found in human language: clicks, implosives, ejectives, and pulmonic consonants.

Japanese Braille is the braille script of the Japanese language. It is based on the original braille script, though the connection is tenuous. In Japanese it is known as tenji (点字), literally "dot characters". It transcribes Japanese more or less as it would be written in the hiragana or katakana syllabaries, without any provision for writing kanji.

Phuthi (Síphùthì) is a Nguni Bantu language spoken in southern Lesotho and areas in South Africa adjacent to the same border. The closest substantial living relative of Phuthi is Swati, spoken in Eswatini and the Mpumalanga province of South Africa. Although there is no contemporary sociocultural or political contact, Phuthi is linguistically part of a historic dialect continuum with Swati. Phuthi is heavily influenced by the surrounding Sesotho and Xhosa languages, but retains a distinct core of lexicon and grammar not found in either Xhosa or Sesotho, and found only partly in Swati to the north.

Ojibwe is an indigenous language of North America from the Algonquian language family. Ojibwe is one of the largest Native American languages north of Mexico in terms of number of speakers and is characterized by a series of dialects, some of which differ significantly. The dialects of Ojibwe are spoken in Canada from southwestern Quebec, through Ontario, Manitoba and parts of Saskatchewan, with outlying communities in Alberta and British Columbia, and in the United States from Michigan through Wisconsin and Minnesota, with a number of communities in North Dakota and Montana, as well as migrant groups in Kansas and Oklahoma.

In a featural writing system, the shapes of the symbols are not arbitrary but encode phonological features of the phonemes that they represent. The term featural was introduced by Geoffrey Sampson to describe the Korean alphabet and Pitman shorthand.

Sesotho verbs are words in the language that signify the action or state of a substantive, and are brought into agreement with it using the subjectival concord. This definition excludes imperatives and infinitives, which are respectively interjectives and class 14 nouns.

The phonology of Sesotho and those of the other Sotho–Tswana languages are radically different from those of "older" or more "stereotypical" Bantu languages. Modern Sesotho in particular has very mixed origins inheriting many words and idioms from non-Sotho–Tswana languages.

Like most other Niger–Congo languages, Sesotho is a tonal language, spoken with two basic tones, high (H) and low (L). The Sesotho grammatical tone system is rather complex and uses a large number of "sandhi" rules.

The orthography of the Sotho language is fairly recent and is based on the Latin script, but, like most languages written using the Latin alphabet, it does not use all the letters; as well, several digraphs and trigraphs are used to represent single sounds.

This article discusses the phonological system of Standard Macedonian based on the Prilep-Bitola dialect. For discussion of other dialects, see Macedonian dialects. Macedonian possesses five vowels, one semivowel, three liquid consonants, three nasal stops, three pairs of fricatives, two pairs of affricates, a non-paired voiceless fricative, nine pairs of voiced and unvoiced consonants and four pairs of stops.

Dania is the traditional linguistic transcription system used in Denmark to describe the Danish language. It was invented by Danish linguist Otto Jespersen and published in 1890 in the Dania, Tidsskrift for folkemål og folkeminder magazine from which the system was named.

![The construction of the syllables of three words in different languages: <Xilo> [Si:lo] "thing" in Xitsonga, <Vhathu> [ba:thu] "people" in Tshivenda, <Ho tletse> [hUt[?]l'e:t[?]s'I] "It is full" in Sesotho. Xilo Vhathu Ho tletse.jpg](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e3/Xilo_Vhathu_Ho_tl%C3%AAtse.jpg/220px-Xilo_Vhathu_Ho_tl%C3%AAtse.jpg)