The Lincoln Memorial is a U.S. national memorial honoring Abraham Lincoln, the 16th president of the United States, located on the western end of the National Mall of Washington, D.C. The memorial is built in a neoclassical style and forms a classical temple. The memorial's architect was Henry Bacon. In 1920, Daniel Chester French designed the large interior Statue of Abraham Lincoln, which was carved in marble by the Piccirilli brothers. Jules Guerin painted the interior murals, and the epitaph above the statue was written by Royal Cortissoz. Dedicated on May 30, 1922, it is one of several memorials built to honor an American president. It has been a major tourist attraction since its opening, and over the years, has occasionally been used as a symbolic center focused on race relations and civil rights.

Grand Central Terminal is a commuter rail terminal located at 42nd Street and Park Avenue in Midtown Manhattan, New York City. Grand Central is the southern terminus of the Metro-North Railroad's Harlem, Hudson and New Haven Lines, serving the northern parts of the New York metropolitan area. It also contains a connection to the Long Island Rail Road through the Grand Central Madison station, a 16-acre (65,000 m2) rail terminal underneath the Metro-North station, built from 2007 to 2023. The terminal also connects to the New York City Subway at Grand Central–42nd Street station. The terminal is the third-busiest train station in North America, after New York Penn Station and Toronto Union Station.

The National Statuary Hall is a chamber in the United States Capitol devoted to sculptures of prominent Americans. The hall, also known as the Old Hall of the House, is a large, two-story, semicircular room with a second story gallery along the curved perimeter. It is located immediately south of the Rotunda. The meeting place of the U.S. House of Representatives for nearly 50 years (1807–1857), after a few years of disuse it was repurposed as a statuary hall in 1864; this is when the National Statuary Hall Collection was established. By 1933, the collection had outgrown this single room, and a number of statues are placed elsewhere within the Capitol.

Ezzard Mack Charles, was an American professional boxer who competed from 1940 to 1959. Known as the Cincinnati Cobra, Charles was respected for his slick defense and precision, and is often regarded as the greatest light heavyweight of all time, and one of the greatest fighters pound for pound, having defeating numerous Hall of Fame fighters in three different weight classes. Charles was the world heavyweight champion from 1949 to 1951, and made eight successful title defenses in under two years.

Lincoln Park is a 1,208-acre (489-hectare) park along Lake Michigan on the North Side of Chicago, Illinois. Named after US President Abraham Lincoln, it is the city's largest public park and stretches for seven miles (11 km) from Grand Avenue, on the south, to near Ardmore Avenue on the north, just north of the DuSable Lake Shore Drive terminus at Hollywood Avenue. Two museums and a zoo are located in the oldest part of the park between North Avenue and Diversey Parkway in the eponymous neighborhood. Further to the north, the park is characterized by parkland, beaches, recreational areas, nature reserves, and harbors. To the south, there is a more narrow strip of beaches east of Lake Shore Drive, almost to downtown. With 20 million visitors per year, Lincoln Park is the second-most-visited city park in the United States, behind Manhattan's Central Park.

Union Square is a historic intersection and surrounding neighborhood in Manhattan, New York City, United States, located where Broadway and the former Bowery Road – now Fourth Avenue – came together in the early 19th century. Its name denotes that "here was the union of the two principal thoroughfares of the island". The current Union Square Park is bounded by 14th Street on the south, 17th Street on the north, and Union Square West and Union Square East to the west and east respectively. 17th Street links together Broadway and Park Avenue South on the north end of the park, while Union Square East connects Park Avenue South to Fourth Avenue and the continuation of Broadway on the park's south side. The park is maintained by the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation.

Chicago Union Station is an intercity and commuter rail terminal located in the West Loop neighborhood of the Near West Side of Chicago. Amtrak's flagship station in the Midwest, Union Station is the terminus of eight national long-distance routes and eight regional corridor routes. Six Metra commuter lines also terminate here.

The Lincoln Tomb is the final resting place of Abraham Lincoln, the 16th president of the United States; his wife Mary Todd Lincoln; and three of their four sons: Edward, William, and Thomas. It is located in Oak Ridge Cemetery in Springfield, Illinois.

Charles Henry Niehaus was an American sculptor.

Cincinnati Union Terminal is an intercity train station and museum center in the Queensgate neighborhood of Cincinnati, Ohio. Commonly abbreviated as CUT, or by its Amtrak station code, CIN, the terminal is served by Amtrak's Cardinal line, passing through Cincinnati three times weekly. The building's largest tenant is the Cincinnati Museum Center, comprising the Cincinnati History Museum, the Museum of Natural History & Science, Duke Energy Children's Museum, the Cincinnati History Library and Archives, and an Omnimax theater.

Spring Grove Cemetery and Arboretum is a nonprofit rural cemetery and arboretum located at 4521 Spring Grove Avenue, Cincinnati, Ohio. At a size of 733 acres, it is the third largest cemetery in the United States, after the Calverton National Cemetery and Abraham Lincoln National Cemetery. The cemetery dates back to 1844 and is recognized as a US National Historic Landmark due to its age, architecture, and notable burials.

Eden Park is an urban park located in the Walnut Hills neighborhood of Cincinnati, Ohio. The hilltop park occupies 186 acres (0.75 km2), and offers numerous overlooks of the Ohio River valley.

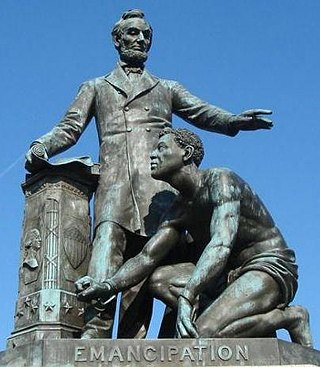

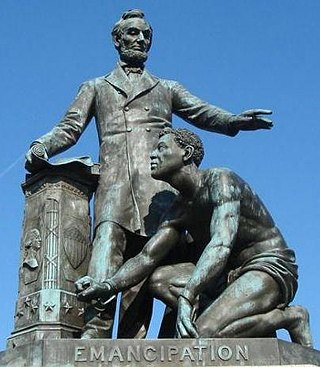

The Emancipation Memorial, also known as the Freedman's Memorial or the Emancipation Group is a monument in Lincoln Park in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Washington, D.C. It was sometimes referred to as the "Lincoln Memorial" before the more prominent national memorial was dedicated in 1922.

Cincinnati is a city in and the county seat of Hamilton County, Ohio, United States. Settled by Europeans in 1788, the city is located on the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line with Kentucky. The population of Cincinnati was 309,317 in 2020, making it the third-most populous city in Ohio and 64th-most populous in the U.S. The city is the economic and cultural hub of the Cincinnati metropolitan area, Ohio's most populous metro area and the nation's 30th-largest, with over 2.271 million residents.

Lincoln Park is an urban park in Jersey City, New Jersey with an area of 273.4 acres (110.6 ha). Part of the Hudson County Park System, it opened in 1905 and was originally known as West Side Park. The park was designed by Daniel W. Langton and Charles N. Lowrie, both founding members of the American Society of Landscape Architects.

The Medici lions are a pair of marble sculptures of lions: one of which is Roman, dating to the 2nd century AD, and the other a 16th-century pendant. By 1598 both were placed at the Villa Medici, Rome. Since 1789 they have been displayed at the Loggia dei Lanzi in Florence. The sculptures depict standing male lions with a sphere or ball under one paw, looking to the side.

Terminal Station, Macon, Georgia, is a railroad station that was built in 1916, and is located on 5th St. at the end of Cherry St. It was designed in the Beaux-Arts style by architect Alfred T. Fellheimer (1875–1959), prominent for his design of Grand Central Terminal in New York City in 1903. The station building is part of the Macon Historic District, which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. While no longer an active train station, it has been the location of the Macon Transit Authority bus hub since 2014.

Cincinnati Union Terminal is an intercity train station and museum center in the Queensgate neighborhood of Cincinnati, Ohio. It opened in 1933 as a union station to replace five train stations serving seven railroads in the city. Passenger service ceased in 1972, and the station concourse was demolished. From 1980 to 1985, the building housed a shopping mall. In 1991, the terminal saw the opening of the Cincinnati Museum Center and the return of Amtrak service.

The Ulysses S. Grant Monument is a presidential memorial in Chicago, honoring American Civil War general and 18th president of the United States, Ulysses S. Grant. Located in Lincoln Park, the statue was commissioned shortly after the president's death in 1885 and was completed in 1891. Several artists submitted sketches, and Louis Rebisso was selected to design the statue, with a granite pedestal suggested by William Le Baron Jenney. At the time of its completion, the monument was the largest bronze statue cast in the United States, and over 250,000 people were present at the dedication of the monument.