Canals are waterway channels, or artificial waterways, for water conveyance, or for servicing water transport vehicles. They carry free surface flow under atmospheric pressure, and can be thought of as artificial rivers.

Ancient Roman architecture adopted the external language of classical Greek architecture for the purposes of the ancient Romans, but was different from Greek buildings, becoming a new architectural style. The two styles are often considered one body of classical architecture. Roman architecture flourished in the Roman Republic and to even a greater extent under the Empire, when the great majority of surviving buildings were constructed. It used new materials, particularly Roman concrete, and newer technologies such as the arch and the dome to make buildings that were typically strong and well-engineered. Large numbers remain in some form across the former empire, sometimes complete and still in use to this day.

A watermill or water mill is a mill that uses hydropower. It is a structure that uses a water wheel or water turbine to drive a mechanical process such as milling (grinding), rolling, or hammering. Such processes are needed in the production of many material goods, including flour, lumber, paper, textiles, and many metal products. These watermills may comprise gristmills, sawmills, paper mills, textile mills, hammermills, trip hammering mills, rolling mills, wire drawing mills.

A water wheel is a machine for converting the energy of flowing or falling water into useful forms of power, often in a watermill. A water wheel consists of a wheel, with a number of blades or buckets arranged on the outside rim forming the driving car.

Trajan's Bridge, also called Bridge of Apollodorus over the Danube, was a Roman segmental arch bridge, the first bridge to be built over the lower Danube and one of the greatest achievements in Roman architecture. Though it was only functional for 165 years, it is often considered to be the longest arch bridge in both total and span length for more than 1,000 years.

The ancient Romans were famous for their advanced engineering accomplishments. Technology for bringing running water into cities was developed in the east, but transformed by the Romans into a technology inconceivable in Greece. The architecture used in Rome was strongly influenced by Greek and Etruscan sources.

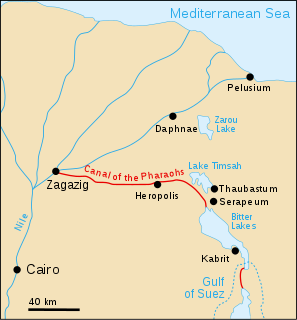

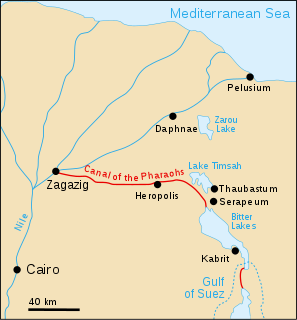

The Canal of the Pharaohs, also called the Ancient Suez Canal or Necho's Canal, is the forerunner of the Suez Canal, constructed in ancient times and kept in use, with intermissions, until being closed for good in 767 AD for strategic reasons during a rebellion. It followed a different course from its modern counterpart, by linking the Nile to the Red Sea via the Wadi Tumilat. Work began under the pharaohs. According to Darius the Great's Suez Inscriptions and Herodotus, the first opening of the canal was under Persian king Darius the Great, but later ancient authors like Aristotle, Strabo, and Pliny the Elder claim that he failed to complete the work. Another possibility is that it was finished in the Ptolemaic period under Ptolemy II, when engineers solved the problem of overcoming the difference in height through canal locks.

Renaissance technology was the set of European artifacts and inventions which spread through the Renaissance period, roughly the 14th century through the 16th century. The era is marked by profound technical advancements such as the printing press, linear perspective in drawing, patent law, double shell domes and bastion fortresses. Sketchbooks from artisans of the period give a deep insight into the mechanical technology then known and applied.

Ancient Greek technology developed during the 5th century BC, continuing up to and including the Roman period, and beyond. Inventions that are credited to the ancient Greeks include the gear, screw, rotary mills, bronze casting techniques, water clock, water organ, the torsion catapult, the use of steam to operate some experimental machines and toys, and a chart to find prime numbers. Many of these inventions occurred late in the Greek period, often inspired by the need to improve weapons and tactics in war. However, peaceful uses are shown by their early development of the watermill, a device which pointed to further exploitation on a large scale under the Romans. They developed surveying and mathematics to an advanced state, and many of their technical advances were published by philosophers, like Archimedes and Heron.

Roman technology is the collection of antiques, skills, methods, processes, and engineering practices which supported Roman civilization and made possible the expansion of the economy and military of ancient Rome.

The Sangarius Bridge or Bridge of Justinian is a late Roman bridge over the river Sakarya in Anatolia, in modern-day Turkey. It was built by the East Roman Emperor Justinian I (527-565 AD) to improve communications between the capital Constantinople and the eastern provinces of his empire. With a remarkable length of 430 m, the bridge was mentioned by several contemporary writers, and has been associated with a supposed project, first proposed by Pliny the Younger to Emperor Trajan, to construct a navigable canal that would bypass the Bosporus.

A ship mill, more commonly known as a boat mill is a type of watermill. The milling and grinding technology and the drive (waterwheel) are built on a floating platform on this type of mill. Its first recorded use dates back to mid-6th century AD Italy.

The Dara Dam was a Roman arch dam at Dara in Mesopotamia, a rare pre-modern example of this dam type. The modern identification of its site is uncertain, but may rather point to a common gravity dam.

The Lake Homs Dam, also known as Qattinah Dam, is a Roman-built dam near the city of Homs, Syria, which is in use to this day

The Hierapolis sawmill was a Roman water-powered stone sawmill at Hierapolis, Asia Minor. Dating to the second half of the 3rd century AD, the sawmill is considered the earliest known machine to combine a crank with a connecting rod to form a crank slider mechanism.

Örjan Wikander is a Swedish classical archaeologist and ancient historian. His main interests are ancient water technology, ancient roof terracottas, Roman social history, Etruscan archaeology and epigraphy.