Ancient Roman architecture adopted the external language of classical ancient Greek architecture for the purposes of the ancient Romans, but was different from Greek buildings, becoming a new architectural style. The two styles are often considered one body of classical architecture. Roman architecture flourished in the Roman Republic and to an even greater extent under the Empire, when the great majority of surviving buildings were constructed. It used new materials, particularly Roman concrete, and newer technologies such as the arch and the dome to make buildings that were typically strong and well engineered. Large numbers remain in some form across the former empire, sometimes complete and still in use today.

Byzantine architecture is the architecture of the Byzantine Empire, or Eastern Roman Empire, usually dated from 330 AD, when Constantine the Great established a new Roman capital in Byzantium, which became Constantinople, until the fall of the Byzantine Empire in 1453. There was initially no hard line between the Byzantine and Roman Empires, and early Byzantine architecture is stylistically and structurally indistinguishable from late Roman architecture. The style continued to be based on arches, vaults and domes, often on a large scale. Wall mosaics with gold backgrounds became standard for the grandest buildings, with frescos a cheaper alternative.

The Pantheon is a former Roman temple and, since AD 609, a Catholic church in Rome, Italy. It was built on the site of an earlier temple commissioned by Marcus Agrippa during the reign of Augustus, then after that burnt down, the present building was ordered by the emperor Hadrian and probably dedicated c. AD 126. Its date of construction is uncertain, because Hadrian chose not to inscribe the new temple but rather to retain the inscription of Agrippa's older temple.

In architecture, a pendentive is a constructional device permitting the placing of a circular dome over a square room or of an elliptical dome over a rectangular room. The pendentives, which are triangular segments of a sphere, taper to points at the bottom and spread at the top to establish the continuous circular or elliptical base needed for a dome. In masonry the pendentives thus receive the weight of the dome, concentrating it at the four corners where it can be received by the piers beneath.

A concrete shell, also commonly called thin shell concrete structure, is a structure composed of a relatively thin shell of concrete, usually with no interior columns or exterior buttresses. The shells are most commonly monolithic domes, but may also take the form of hyperbolic paraboloids, ellipsoids, cylindrical sections, or some combination thereof. The first concrete shell dates back to the 2nd century.

St. Gereon's Basilica is a German Roman Catholic church in Cologne, dedicated to Saint Gereon, and designated a minor basilica on 25 June 1920. The first mention of a church at the site, dedicated to St. Gereon, appears in 612. However, the building of the current choir gallery, apse, and transepts occurred later, beginning under Archbishop Arnold II von Wied in 1151 and ending in 1227. It is one of twelve great churches in Cologne that were built in the Romanesque style.

Roman concrete, also called opus caementicium, was used in construction in ancient Rome. Like its modern equivalent, Roman concrete was based on a hydraulic-setting cement added to an aggregate.

The Roman architectural revolution, also known as the concrete revolution, is the name sometimes given to the widespread use in Roman architecture of the previously little-used architectural forms of the arch, vault, and dome. For the first time in history, their potential was fully exploited in the construction of a wide range of civil engineering structures, public buildings, and military facilities. These included amphitheaters, aqueducts, baths, bridges, circuses, dams, roads, and temples.

Heather Lechtman is an American materials scientist and archaeologist, and Director at the Center for Materials Research in Archaeology and Ethnology (CMRAE) at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. She specializes in prehistoric technology of the Andean area of South America, and in particular metallurgy.

The pozzolanic activity is a measure for the degree of reaction over time or the reaction rate between a pozzolan and Ca2+ or calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)2) in the presence of water. The rate of the pozzolanic reaction is dependent on the intrinsic characteristics of the pozzolan such as the specific surface area, the chemical composition and the active phase content.

Greek lyric is the body of lyric poetry written in dialects of Ancient Greek. It is primarily associated with the early 7th to the early 5th centuries BC, sometimes called the "Lyric Age of Greece", but continued to be written into the Hellenistic and Imperial periods.

Domes were a characteristic element of the architecture of Ancient Rome and of its medieval continuation, the Byzantine Empire. They had widespread influence on contemporary and later styles, from Russian and Ottoman architecture to the Italian Renaissance and modern revivals. The domes were customarily hemispherical, although octagonal and segmented shapes are also known, and they developed in form, use, and structure over the centuries. Early examples rested directly on the rotunda walls of round rooms and featured a central oculus for ventilation and light. Pendentives became common in the Byzantine period, provided support for domes over square spaces.

The Castle of Mau Vizinho is a medieval castle situated in the civil parish of Cimo de Vila da Castanheira, in the municipality of Chaves, district of Vila Real. Also referred to as the Castle of Moors, it is literally translated as the Castle of the Bad Neighbour

The Roman villa of Freiria is a Roman villa in the civil parish of São Domingos de Rana, in the Portuguese municipality of Cascais.

Ludwig Theodor Ferdinand Max Wallraf was a German politician who served as mayor of Cologne from 1907 to 1917. He was State Minister of the Interior from 1917 to 1918. As a German National People's Party politician, he was a member of the Reichstag from 1924 to 1930 and briefly served as its President in 1924/25.

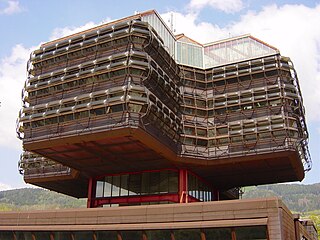

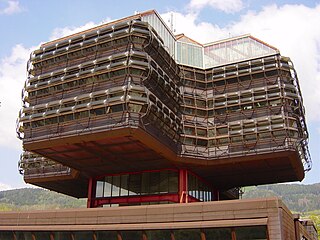

Eilfried Huth is an Austrian architect who lives and works in Graz. Huth is best known for participatory housing projects, in which future residents of the housing estates are included in the planning process.