This is a list of protected areas in Belize.

This is a list of protected areas in Belize.

In Belize, national parks are areas designed for the protection and preservation of natural and aesthetic features of national significance for the benefit and enjoyment of the people. Therefore, they are areas of recreatitourism, as well as environmental protection. National parks are gazetted under the National Parks System Act of 1981. [1] They are administered by the Forest Department and managed through partnership agreements with community-based non-governmental organisations.

| Reserve | District | Size (ha) | Size (acres) | IUCN | Co-management | Est. | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aguas Turbias | Orange Walk | 3,541 | 8,750 | II | — [note 1] | 1994 | [2] |

| Bacalar Chico | Belize | 4,510 | 11,100 | V | Green Reef Environmental Institute [note 2] | 1996 | Excludes adjacent marine reserve. [3] [4] |

| Billy Barquedier | Stann Creek | 663 | 1,640 | II | Steadfast Tourism and Conservation Association | 2001 | [5] |

| Chiquibul | Cayo | 106,839 | 264,000 | II | Friends for Conservation and Development | 1995 | Excludes adjacent forest reserve. [6] [7] |

| Five Blues Lake | Cayo | 1,643 | 4,060 | II | Friends of Five Blues Lake National Park | 1994 | [8] |

| Gra Gra Lagoon | Stann Creek | 534 | 1,320 | II | Friends of Gra Gra Lagoon | 2002 | [9] |

| Guanacaste | Cayo | 23 | 57 | II | Belize Audubon Society | 1994 | [10] [11] |

| Honey Camp | Corozal / Orange Walk | 3,145 | 7,770 | II | Corozal Sustainable Future Initiative [note 3] | 2001 | [12] |

| Laughing Bird Caye | Stann Creek | 4,095 | 10,120 | II | Southern Environmental Association | 1996 | [13] [14] |

| Mayflower Bocawina | Stann Creek | 2,868 | 7,090 | II | Friends of Mayflower Bocawina National Park | 2001 | [15] [16] |

| Monkey Bay | Belize | 859 | 2,120 | II | Guardians of the Jewel [note 2] | 1994 | [17] [18] |

| Nojkaaxmeen Elijio Panti | Cayo | 5,130 | 12,700 | II | Belize Development Foundation [note 4] | 2001 | [19] [20] [21] |

| Payne's Creek | Toledo | 14,739 | 36,420 | II | Toledo Institute for Development and Environment | 1994 | [22] [23] |

| Peccary Hills | Belize | 4,260 | 10,500 | II | Gracie Rock Reserve for Adventure, Culture and Ecotourism | 2007 | [24] [25] |

| Río Blanco | Toledo | 38 | 94 | II | Río Blanco Mayan Association | 1994 | [26] |

| Sarstoon-Temash | Toledo | 16,938 | 41,850 | II | Sarstoon Temash Institute for Indigenous Management | 1994 | Ramsar site. [27] [28] |

| St. Herman's Blue Hole | Cayo | 269 | 660 | II | Belize Audubon Society | 1986 | [29] [30] |

A natural monument is designated for the preservation of unique geographic features of the landscape. The designation is primarily based on a feature's high scenic value, but may also be regarded as a cultural landmark that represents or contributes to a national identity.

Natural monuments are gazetted under the National Parks System Act of 1981; [1] marine-based monuments additionally come under the Fisheries Act. Of the five natural monuments in the country, three are terrestrial, administered by the Forest Department, while the remaining two are marine-based and come under the authority of the Fisheries Department.

| Image | Reserve | District | Size (ha) | Size (acres) | IUCN | Co-management | Est. | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

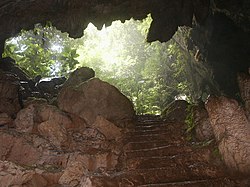

| Actun Tunichil Muknal | Cayo | 185 | 460 | Ia | Belize Audubon Society; Institute of Archaeology | 2004 | Terrestrial. [31] [32] |

| Blue Hole | Belize | 414 | 1,020 | III | Belize Audubon Society | 1996 | Marine. [33] [34] [35] |

| Half Moon Caye | Belize | 3,954 | 9,770 | II | Belize Audubon Society | 1982 | Marine. [36] [37] |

| Thousand Foot Falls | Cayo | 522 | 1,290 | III | Belize Karst Habitat Conservation | 2004 | Terrestrial. [38] |

| Victoria Peak | Stann Creek | 1,959 | 4,840 | III | Belize Audubon Society | 1998 | Terrestrial. [39] [40] |

The country's three nature reserves enjoy the highest level of protection within the National Protected Areas System Plan. The designation was created for the strict protection of biological communities or ecosystems, and the maintenance of natural processes in an undisturbed state. They are typically pristine, wilderness ecosystems.

Nature reserves are legislated under the National Parks System Act of 1981. [1] It is the strictest designation of all categories within the country's national protected areas system, with no extractive use or tourism access permitted. Permits are required to enter the area and are restricted to researchers only. The nature reserves are under the authority of the Forest Department.

The oldest of these, Bladen Nature Reserve, forms the centrepiece of the Maya Mountains biological corridor, and is considered one of the most biodiversity-rich, and topographically unique areas within the Mesoamerican biodiversity hotspot.

| Reserve | District | Size (ha) | Size (acres) | IUCN | Co-management | Est. | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bladen | Toledo | 40,411 | 99,860 | Ia | Ya’axché Conservation Trust; Bladen Management Consortium | 1990 | [41] [42] |

| Burdon Canal | Belize | 2,126 | 5,250 | Ia | — [note 5] | 1992 | [43] |

| Tapir Mountain | Cayo | 2,543.85 | 6,286.0 | Ia | Belize Karst Habitat Conservation | 1994 | Formerly known as Society Hall Nature Reserve. [44] [45] |

Wildlife sanctuaries are created for the preservation of an important keystone species in the ecosystem. By preserving enough area for them to live in, many other species receive the protection they need as well.

Wildlife sanctuaries are gazetted under the National Parks System Act of 1981, and are the responsibility of the Forest Department. [1] There are currently seven wildlife sanctuaries, three of which are being managed under co-management partnerships, whilst the other four are managed under informal arrangements. Two of the following wildlife sanctuaries are considered to be marine protected areas, and may also have collaborative agreements with the Fisheries Department in place.

| Reserve | District | Size (ha) | Size (acres) | IUCN | Co-management | Est. | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aguacaliente | Toledo | 2,213 | 5,470 | IV | Aguacaliente Management Team [note 2] | 1998 | Terrestrial. [46] [47] |

| Cockscomb Basin | Stann Creek / Toledo | 49,477 | 122,260 | IV | Belize Audubon Society | 1997 | Terrestrial. [48] |

| Corozal Bay | Belize / Corozal | 73,049 | 180,510 | IV | Sarteneja Alliance for Conservation and Development [note 2] | 1998 | Marine. [49] [50] |

| Crooked Tree | Belize / Orange Walk | 15,372 | 37,990 | IV | Belize Audubon Society | 1984 | Ramsar site. Boundaries ill-defined. Terrestrial. [51] |

| Gales Point | Belize | 3,681 | 9,100 | IV | Gales Point Wildlife Sanctuary Community Management Committee [note 2] | 1998 | Terrestrial. [52] [53] |

| Spanish Creek | Belize / Orange Walk | 2,428 | 6,000 | IV | Rancho Dolores Development Group [note 2] | 2002 | Terrestrial. [54] |

| Swallow Caye | Belize | 3,631 | 8,970 | IV | Friends of Swallow Caye | 2002 | Marine. [55] [56] |

Forest reserves, overseen by the Forest Department, are designed for the sustainable extraction of timber without destroying the biodiversity of the location. These are gazetted under the Forests Act of 1927, [57] which allows the department to grant permits to logging companies after extensive review. There are currently 16 forest reserves with a combined acreage of 380,328 hectares (939,810 acres), making up 9.3% of total national territory. [58]

| Reserve | District | Size (ha) | Size (acres) | IUCN | Est. | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caye Caulker | Belize | 38 | 94 | VI | 1998 | Excludes adjacent marine reserve. [59] |

| Chiquibul | Cayo | 59,822 | 147,820 | VI | 1995 | Excludes adjacent national park. [60] |

| Columbia River | Cayo / Toledo | 60,016 | 148,300 | VI | 1997 | [61] |

| Deep River | Toledo | 27,232 | 67,290 | VI | [62] | |

| Fresh Water Creek | Corozal / Orange Walk | 13,513 | 33,390 | VI | 1926 | [63] |

| Grants Work | Stann Creek | 3,199 | 7,900 | VI | 1989 | [64] |

| Machaca | Toledo | 1,253 | 3,100 | VI | 1998 | [65] |

| Manatee | Belize / Stann Creek | 36,621 | 90,490 | VI | 1959 | [66] |

| Mango Creek | Stann Creek / Toledo | 12,090 | 29,900 | VI | 1989 | Comprises two separate segments. [67] [68] |

| Monkey Caye | Toledo | 669 | 1,650 | VI | 1996 | [69] |

| Mountain Pine Ridge | Cayo | 43,372 | 107,170 | VI | 1944 | [70] [71] |

| Maya Mountain | Stann Creek | 16,887 | 41,730 | VI | 1997 | [72] |

| Sibun | Cayo | 32,849 | 81,170 | VI | 1959 | [73] [71] |

| Sittee River | Stann Creek | 37,360 | 92,300 | VI | [74] | |

| Swasey Bladen | Toledo | 5,980 | 14,800 | VI | 1989 | [75] |

| Vaca | Cayo | 14,118 | 34,890 | VI | 1991 | [76] |

Marine reserves are designed for the conservation of aquatic ecosystems, including marine wildlife and its environment. The majority of these reserves contribute to the conservation of Belize's Barrier Reef, which provides a protective shelter for pristine atolls, seagrass meadows and rich marine life. The preservation of the Barrier Reef system has been recognised as a global interest through the collective designation of seven protected areas, including four of the following marine reserves, as a World Heritage Site.

Marine reserves are legislated under the Fisheries Act, and are administered by the Fisheries Department. One of the department's key responsibilities is to ensure the sustainable extraction of marine resources. There are currently eight marine reserves, management of which is either direct, by the department, or in partnership with non-governmental agencies.

| Reserve | District | Size (ha) | Size (acres) | IUCN | Co-management | Est. | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacalar Chico | Belize | 6,391 | 15,790 | IV | Green Reef Environmental Institute [note 2] | 1996 | Excludes adjacent national park. Divided into two zones: a conservation zone, [77] and a general use zone. [78] [4] |

| Caye Caulker | Belize | 3,913 | 9,670 | VI | Forest & Marine Reserves Association of Caye Caulker | 1998 | Excludes adjacent forest reserve. [79] |

| Gladden Spit and Silk Cayes | Stann Creek | 10,514 | 25,980 | IV | Southern Environmental Association | 2000 | Divided into two zones: a general use zone, [80] and a conservation zone. [81] [82] [83] |

| Glover's Reef | Belize | 86,653 | 214,120 | IV | — | 1993 | In 2001, the reserve was divided into four zones: a general use zone, [84] a conservation zone, [85] a seasonal closure zone, [86] and a wilderness zone. [87] A spawning aggregation zone was broken off in 2003 and comes under separate management (see below). |

| Hol Chan | Belize | 1,444 | 3,570 | II | Hol Chan Trust Fund | 1987 | Divided into four zones: Mangrove, [88] Seagrass, [89] Shark Ray Alley, [90] and Coral Reef. [91] [92] |

| Port Honduras | Toledo | 40,470 | 100,000 | IV | Toledo Institute for Development and Environment | 2000 | Divided into two zones: a general use zone, [93] and a conservation zone. [94] |

| Sapodilla Cayes | Toledo | 15,618 | 38,590 | IV | Southern Environmental Association | 1996 | [95] |

| South Water Caye | Stann Creek | 47,702 | 117,870 | IV | — | 1996 | [96] [97] |

| Aggregation zone | District | Size (ha) | Size (acres) | IUCN | Est. | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dog Flea | Belize | 576 | 1,420 | IV | 2003 | [98] |

| Emily or Glory Caye | Belize | 0 | 0 | IV | 2003 | [99] |

| Gladden Spit | Belize | 1,617 | 4,000 | IV | 2003 | Managed as part of Gladden Spit and Silk Cayes Marine Reserve. [100] |

| Nicholas Caye | Belize | 673 | 1,660 | IV | 2003 | Managed as part of Sapodilla Marine Reserve. [101] |

| Northern Glover's Reef | Belize | 621 | 1,530 | IV | 2003 | Managed as part of Glover's Reef Marine Reserve. [102] |

| Rise and Fall Bank | Belize | 1,721 | 4,250 | IV | 2003 | [103] |

| Rocky Point | Belize | 570 | 1,400 | IV | 2003 | Managed as part of Bacalar Chico Marine Reserve. [104] |

| Sandbore | Belize | 521 | 1,290 | IV | 2003 | [105] |

| Seal Caye | Toledo | 648 | 1,600 | IV | 2003 | [106] |

| South Point Lighthouse | Belize | 533 | 1,320 | IV | 2003 | [107] |

| South Point Turneffe | Belize | 558 | 1,380 | IV | 2003 | [108] |

The seven bird sanctuaries are some of the country's oldest protected areas established for the purpose of biodiversity conservation. They were gazetted in 1977 as crown reserves for the protection of waterfowl nesting and roosting colonies. [58] They were later reorganised under the National Parks System Act in 1981. [1] They are under the jurisdiction of the Forest Department. All of them are tiny islands with a combined surface area of 6 hectares (15 acres). [58]

All the sanctuaries are nesting and roosting sites for wading birds, though the species vary.

| Reserve | District | Size (ha) | Size (acres) | IUCN | Est. | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bird Caye | Belize | 0.5 | 1.2 | IV | 1977 | [109] |

| Doubloon Bank | Orange Walk | 1.5 | 3.7 | IV | 1977 | [110] |

| Little Guana Caye | Belize | 1 | 2.5 | IV | 1977 | [111] |

| Los Salones | Belize | 1 | 2.5 | IV | 1977 | [112] |

| Monkey Caye | Toledo | 0.5 | 1.2 | IV | 1977 | [113] |

| Man of War Caye | Stann Creek | 1 | 2.5 | IV | 1977 | [114] |

| Unnamed Caye | Belize | 0.5 | 1.2 | IV | 1977 | [115] |

Before the arrival of Europeans in America, Belize lay in the heartland of the Maya civilisation, and consequently contains some of the earliest and most important Maya ruins. [117] Archaeological findings at Caracol, in the southern end of the country, have suggested that it formed the centre of political struggles in the southern Maya lowlands. [117] The complex covered an area much larger than present-day Belize City and supported more than twice the modern city's population. [116] Meanwhile, Lamanai, in the north, is known for being the longest continually-occupied site in Mesoamerica, settled during the early Preclassic era and continuously occupied up to and during the area's colonisation. [117]

While the majority of reserves under this category are related to the pre-colonial era, Serpon Sugar Mill and Yarborough Cemetery, both designated in 2009, only date from the 19th century and are alternatively described as historical reserves. [118]

The country's 15 archaeological sites are managed by the Institute of Archaeology, a branch of the National Institute of Culture and History (NICH), [58] which comes under the authority of the Ministry of Culture. [119] This type of protected area was gazetted under the Ancient Monuments and Antiquities Act, 1 May 1972. [58] [120] All of the following reserves are open to the public. Many other sites, such as Cuello and Uxbenka, are located on private land and can only be visited if prior permission is obtained from the landowner. [117]

| Image | Reserve | District | Size (ha) | Size (acres) | IUCN | Est. | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Altun Ha | Belize | 15.5 | 38 | II | 1995 | [121] [122] |

| Barton Creek | Belize | 2.0 | 4.9 | II | 2003 | [123] [124] |

| Cahal Pech | Cayo | 9.0 | 22 | II | 1995 | [125] [126] |

| Caracol | Cayo | 10,339 | 25,550 | II | 1995 | [127] [128] |

| Cerro Maya | Corozal | 10 | 25 | II | 1976 | [129] [130] |

| El Pilar | Cayo | 771 | 1,910 | II | 1998 | [131] [132] |

| Lamanai | Orange Walk | 396 | 980 | II | 1985 | [133] [134] |

| Lubaantun | Toledo | 16 | 40 | II | 1995 | [135] [136] |

| Marco Gonzalez | Belize | 3.1 | 7.7 | II | 2011 | [117] [137] | |

| Nim Li Punit | Toledo | 24 | 59 | II | 1985 | [138] [139] |

| Nohoch Che'en | Cayo | 7 | 17 | II | 2010 | Also known as Caves Branch. Formerly a private reserve owned by Jaguar Paw. [140] [141] | |

| Santa Rita | Corozal | 0.1 | 0.25 | II | 1995 | [142] [143] | |

| Serpon Sugar Mill | Stann Creek | 13 | 32 | II | 2009 | [118] [144] | |

| Xunantunich | Cayo | 3 | 7.4 | II | 1995 | [145] [146] |

| Yarborough Cemetery | Belize | 0.5 | 1.2 | II | 2009 | [147] |

Private reserves are owned and operated by non-governmental conservation initiatives, and enjoy various levels of protection. Most of them are essentially multiple-use reserves, and include managed extraction of resources. [58]

In 2003, the Belize Association of Private Protected Areas (BAPPA) was formed to assist in the co-ordinatation of private conservation initiatives as a cohesive group, and to represent and assist landowners in attaining recognition from the Belizean government and integration into the national protected areas system. [148] It maintains a directory of landowners that are attempting to manage their land holdings for conservation purposes. [58]

A total of eight private reserves have so far been officially recognised as national protected areas. [148] While most of these recognised reserves have no formal or legal commitment to remain under conservation management, there are additional private landholdings which are considered to be very effective in biodiversity conservation and critical to the national protected areas system, but which are not yet recognised within the system. Formal adoption and implementation of proposed legislation to manage and regulate such areas is required to attain such recognition.

As of January 2005, a total of eight private reserves were officially recognised as being part of the country's national protected areas system. [148] Two have a standing agreement with the government, while the remaining six have their own management system in place. [58] Of the following, Aguacate Lagoon is the only non-participatory reserve, its management expressing little interest in being part of the system.

They cover a combined total area of approximately 131,663 hectares (325,350 acres). [58]

| Reserve | District | Size (ha) | Size (acres) | IUCN | Management | Est. | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aguacate Lagoon | Cayo | 115 | 280 | IV | Aguacate Park | 1987 | [149] |

| Block 127 | Toledo | 3,736 | 9,230 | IV | Toledo Institute for Development and Environment | 2001 | Forms one block of the TIDE Private Protected Lands, which total 12,000 hectares (30,000 acres). [150] [151] |

| Community Baboon Sanctuary | Belize | 5,253 | 12,980 | IV | Women's Conservation Group | 1985 | [152] [153] |

| Golden Stream | Toledo | 6,085 | 15,040 | IV | Ya’axché Conservation Trust; Fauna & Flora International | 1998 | Formally known as Golden Stream Corridor Preserve. [154] [155] |

| Monkey Bay | Belize | 465 | 1,150 | IV | Monkey Bay Wildlife Sanctuary | 1987 | Formally known as Monkey Bay Wildlife Sanctuary. [156] [157] |

| Río Bravo | Orange Walk | 104,897 | 259,210 | IV | Programme for Belize | 1988 | Formally known as Río Bravo Conservation and Management Area. [158] [159] [160] |

| Runaway Creek | Belize | 2,431 | 6,010 | IV | Foundation for Wildlife Conservation; Birds Without Borders | 1998 | [161] [162] |

| Shipstern | Corozal | 8,228 | 20,330 | IV | International Tropical Conservation Foundation; Papiliorama-Nocturama Foundation | 1987 | Formally known as Shipstern Nature Reserve. [163] [164] |

| Reserve | District | Size (ha) | Size (acres) | IUCN | Management | Est. | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balam Na | Corozal | 166 | 410 | IV | Wildtracks; Tropical Rainforest Coalition | 2000 | [165] [166] |

| Belize Maya Forest | Orange Walk | 95,500 | 236,000 | Belize Maya Forest Trust | 2021 | Adjacent to Rio Bravo Reserve [167] [168] | |

| BFREE | Toledo | 572 | 1,410 | IV | Belize Foundation for Research & Environmental Education | 1995 | [169] [170] |

| Boden Creek | Toledo | 5,447 | 13,460 | IV | Belize Lodge and Excursions | 1998 | Formally known as Boden Creek Ecological Preserve. [171] [172] |

| Fireburn | Corozal | 745 | 1,840 | IV | Wildtracks; Fireburn Community | [173] [174] | |

| Gallon Jug | Orange Walk | 54,154 | 133,820 | IV | Gallon Jug Estate | [175] [176] | |

| Green Hills | Cayo | 43 | 110 | IV | Meerman, Jan | 1996 | Formally known as Green Hills Private Conservation Management Area. [177] [178] |

| Hidden Valley | Cayo | 2,925 | 7,230 | IV | Hidden Valley Institute | [179] [180] |

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty |url= (help)