Sultanate of Melaka

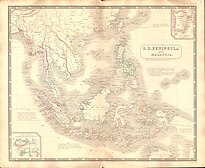

During the realm of the Sultanate, Melaka was an important trading port and the maintenance of law and order was crucial to its prosperity. The administration of justice was placed under the direct charge of the Bendahara (or chief minister) who exercised both political and judicial functions. The Temenggung (which is the commander of troops and police) was responsible for apprehending criminals, maintaining prisons and generally keeping the peace. The welfare of foreigners residing in the state was looked after by several Shahbandars (harbour masters and collectors of customs).

Little is known of the legal system in those days but it is generally accepted that the law administered then was a combination of Muslim law and the "Adat Temenggung" (patriarchal Malay customary law). The "Adat Temengung" was the law of the Sultan or the law ordained by the rulers and later adopted in the other regions of Peninsular Malaysia. It was the basis of the law as found in Malay legal digests compiled between the 15th and 19th centuries.

The formal legal text of traditional Melaka consisted of the Undang-Undang Melaka (Laws of Melaka), variously called the Hukum Kanun Melaka and Risalat Hukum Kanun, and the Undang-Undang Laut Melaka (the Maritime Laws of Melaka). [1] The laws as written in the legal digests went through an evolutionary process. The legal rules that eventually evolved were shaped by three main influences, namely the early non-indigenous Hindu/Buddhist tradition, Islam and the indigenous "adat".

European and British influence

When Melaka fell into the hands of the Portuguese from 1511 to 1641 and the Dutch from 1641 till 1786, the local people continued to practise Islamic laws and Malay customs. It could be said that the Portuguese and the Dutch laws made relatively little impact on the legal system as a whole other than the political and administrative structures.

In 1786, Britain acquired the island of Penang, the first territory in Malaysia to fall into British hands. The main preoccupation of the British administrators during the first decades after the founding of Penang, was the maintenance of some form of order and to this end, local customs and law were allowed to continue but tempered by such portions of the English law as were considered just and expedient. Some judgements meted out may seem rather strange by today's standard but it should be borne in mind that they merely reflected the harsh and often chaotic conditions of those pioneering days. Complaints and petitions were made over many years for a better system of administering justice. Finally, it came in the form of the Royal Charter of Justice of 1807. The Charter is the most significant event in Malaysian legal history as it marked the beginning of the statutory introduction of English law into this country. The Charter established the Court of Judicature of the Prince of Wales' island (as Penang was then known) to exercise jurisdiction in all civil, criminal and ecclesiastical matters. It was interpreted by the courts as introducing to Penang the law of England as it stood in 1807 insofar as it was suitable to local conditions and circumstances.

When Penang, Singapore, which was founded by the British in 1819 along with Melaka, which fell to the British as a trade-off under the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824, formed the Straits Settlement in 1826, a new charter, the Charter of Justice was introduced. A new court called 'The Court of Judicature of Prince of Wales' Island, Singapore and Melaka" was created by this Charter. Penang in a sense had a second statutory reception of English law although it was the first for Singapore and Melaka. In one stroke of the pen, the Straits Settlements received a large dose of English law.

Despite the new Charter, the administration of justice was far from satisfactory. A third Charter of Justice was granted in 1855 which enabled the reorganisation of the court system. In 1867, when the administration of the Straits Settlements from India was transferred to the Colonial Office, the court system was reorganised once again. By Ordinance 5 of 1868, the Court of Judicature of Prince of Wales' Island, Singapore and Melaka was abolished. A new court known as the Supreme Court of the Straits Settlements was established. In 1873, the Supreme Court was further reorganised under four judges – the Chief Justice, the Justice of Penang, the Senior Puisne Judge and the Junior Puisne Judge. The Court of Quarter Sessions was established as a criminal court and presided over by the Senior and Junior Puisne Judges in Singapore and Penang respectively. A Court of Appeal was also constituted. By then, the judiciary had slowly evolved into its modern form.

Few of the British Indian statutes were imported in the Federated Malay States through the British Residents, including the Penal Code, the Contract Ordinance, the Criminal Procedure Code, and the Civil Procedure Code. [2] : 222

English commercial law was formally introduced into the Straits Settlements by Section 6 of the Civil Law Ordinance, 1878. This provision, as re-enacted in the Civil Law Act, 1956 (Revised 1972), is still applicable in Penang and Melaka.

English land law was specifically excluded by sub-section 2. The whole section of this Ordinance was incorporated into the Civil Law Ordinance of 1909 and later re-enacted as Section 5 of the Civil Law Ordinance (Chap. 42 of the 1936 Revised Edition). This was the legal situation in the Straits Settlements until its dissolution in 1946 following the formation of the Malayan Union.

The statutory introduction of English law to the Federated Malay States comprising the states of Perak, Selangor, Pahang and Negeri Sembilan occurred in 1937 with the introduction of the Civil Law Enactment, 1937. The Unfederated Malay States, consisting the states of Kedah, Perlis, Kelantan, Terengganu and Johor, became part of the Federation of Malaya in 1948 and the Civil Law (Extension) Ordinance, 1951, extended the application of the Enactment to these states.

Law of Sarawak Ordinance 1928 established as statutory authority for introduction of English law into Sarawak, later substituted with the Application of Laws Ordinance 1949 for broader application. Civil Law Ordinance 1938 established as statutory authority for introduction of English law into North Borneo, later substituted with the Application of Laws Ordinance 1951 for broader application. [2] : 66–67, 161

Both enactments were replaced by the Civil Law Ordinance, 1956, which applied to all eleven states of the Federation. When Malaysia was established in 1963, it became necessary to harmonise the law to take effect in Sabah and Sarawak. The 1956 Ordinance was then superseded by the Civil Law Act, 1956 (revised 1972) which came into force on 1 April 1972.

Adat is a generic term derived from Arabic to describe a variety of local customary practices and traditions deemed compatible with Islam as observed by Muslim communities in the Balkans, North Caucasus, Central Asia, and Southeast Asia. Despite its Arabic origin, the term adat resonates deeply throughout Maritime Southeast Asia, where due to colonial influence, its usage has been systematically institutionalised into various non-Muslim communities. Within the region, the term refers, in a broader sense, to the customary norms, rules, interdictions, and injunctions that guide individuals' conduct as members of the community and the sanctions and forms of address by which these norms and rules are upheld. Adat also includes the set of local and traditional laws and dispute resolution systems by which these societies are regulated.

Sultan Sir Abu Bakar Al-Khalil Ibrahim Shah ibni Almarhum Maharaja Tun Daeng Ibrahim was the Temenggong of Johor. He was the 1st sultan of modern Johor, the 21st Sultan of Johor and the first Maharaja of Johor from the House of Temenggong. He was also informally known as "The Father of Modern Johor", as many historians accredited Johor's development in the 19th century to Abu Bakar's leadership. He initiated policies and provided aids to ethnic Chinese entrepreneurs to stimulate the development of the state's agricultural economy which was founded by Chinese migrants from southern China in the 1840s. He also took charge of the development of Johor's infrastructure, administrative system, military and civil service, all of which were modelled closely along Western lines.

The legal system of Singapore is based on the English common law system. Major areas of law – particularly administrative law, contract law, equity and trust law, property law and tort law – are largely judge-made, though certain aspects have now been modified to some extent by statutes. However, other areas of law, such as criminal law, company law and family law, are largely statutory in nature.

Malaysian nationality law details the conditions by which a person is a citizen of Malaysia. The primary law governing nationality requirements is the Constitution of Malaysia, which came into force on 27 August 1957.

The Supreme Court of Singapore is a set of courts in Singapore, comprising the Court of Appeal and the High Court. It hears both civil and criminal matters. The Court of Appeal hears both civil and criminal appeals from the High Court. The Court of Appeal may also decide a point of law reserved for its decision by the High Court, as well as any point of law of public interest arising in the course of an appeal from a court subordinate to the High Court, which has been reserved by the High Court for decision of the Court of Appeal.

The High Court of Singapore is the lower division of the Supreme Court of Singapore, the upper division being the Court of Appeal. The High Court consists of the chief justice and the judges of the High Court. Judicial Commissioners are often appointed to assist with the Court's caseload. There are two specialist commercial courts, the Admiralty Court and the Intellectual Property Court, and a number of judges are designated to hear arbitration-related matters. In 2015, the Singapore International Commercial Court was established as part of the Supreme Court of Singapore, and is a division of the High Court. The other divisions of the high court are the General Division, the Appellate Division, and the Family Division. The seat of the High Court is the Supreme Court Building.

The Court of Appeal of Singapore is the highest court in the judicial system of Singapore. It is the upper division of the Supreme Court of Singapore, the lower being the High Court. The Court of Appeal consists of the chief justice, who is the president of the Court, and the judges of the Court of Appeal. The chief justice may ask judges of the High Court to sit as members of the Court of Appeal to hear particular cases. The seat of the Court of Appeal is the Supreme Court Building.

The Ministry of Law is a ministry of the Government of Singapore responsible for the advancement in access to justice, the rule of law, the economy and society through policy, law and services.

The law of Malaysia is mainly based on the common law legal system. This was a direct result of the colonisation of Malaya, Sarawak, and North Borneo by Britain between the early 19th century to the 1960s. The supreme law of the land—the Constitution of Malaysia—sets out the legal framework and rights of Malaysian citizens.

The Federal Court of Malaysia is the highest court and the final appellate court in Malaysia. It is housed in the Palace of Justice in Putrajaya. The court was established during Malaya's independence in 1957 and received its current name in 1994.

The Malaysian Bar is a professional body which regulates the profession of lawyers in peninsular Malaysia. In Malaysia, there is no distinction between a barrister and a solicitor, in that, it is a fused profession. Membership into the Bar is automatic and mandatory. The bar was created under the Legal Profession Act 1976. Like other bar associations around the world, it has a wide range of functions, including, to protect the reputation of the legal profession, to uphold the cause of justice, to express its views on matters relating to legislations, and others.

The Royal Malaysia Police trace their existence to the Malacca Sultanate in the 1400s and developed through administration by the Portuguese, the Dutch, modernization by the British beginning in the early 1800s, and the era of Malaysian independence.

The foundation of the Constitution of Malaysia was laid on 10 September 1877. It began with the first meeting of the Council of State in Perak, where the Yang di-Pertuan Agong first started to assert their influence in the Malay states. Under the terms of the Pangkor Engagement of 1874 between the Sultan of Perak and the British, the Sultan was obliged to accept a British Resident. Hugh Low, the second British Resident, convinced the Sultan to set up advisory Council of State, the forerunner of the state legislative assembly. Similar Councils were constituted in the other Malay states as and when they came under British protection.

Richard James Wilkinson was a British colonial administrator, scholar of Malay, and historian. The son of a British consul, Richard James Wilkinson was born in 1867 in Salonika (Thessaloniki) in the Ottoman Empire. He studied at Felsted School and was an undergraduate of Trinity College, Cambridge. He was multilingual and had a command of French, German, Greek, Italian and Spanish, and later, Malay and Hokkien which he qualified in, in 1889, while a cadet after joining the Straits Settlements Civil Service. He was an important contributor to the Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society (JMBRAS). On 7 November 1900 Wilkinson presented a collection of Malay manuscripts and printed books to the University of Cambridge Library. He was appointed CMG in 1912.

Undang-Undang Melaka, also known as Hukum Kanun Melaka, Undang-Undang Darat Melaka and Risalah Hukum Kanun, was the legal code of Melaka Sultanate (1400–1511). It contains significant provisions that reaffirmed the primacy of Malay customary law or adat, while at the same time accommodating and assimilating Islamic principles. The legal code is believed originally compiled during the reign of Muhammad Shah (1424–1444), before it was continuously expanded and improved by the succeeding sultans. The Melaka system of justice as enshrined in the Undang-Undang Melaka was the first digest of laws, compiled in the Malay world. It became a legal resource for other major regional sultanates like Johor, Perak, Brunei, Pattani and Aceh, and has been regarded as the most important of Malay legal digests.

Classical Malay literature, also known as traditional Malay literature, refers to the Malay-language literature from the Malay world, consisting of areas now part of Brunei, Singapore, Malaysia, and Indonesia; works from countries such as the Philippines and Sri Lanka have also been included. It shows considerable influences from Indian literature as well as Arabic and Islamic literature. The term denotes a variety of works, including the hikayat, poetry, history, and legal works.

The Penang High Court, founded in 1808, is the birthplace of Malaysia's judiciary system. It is housed inside a Palladian-style building at Light Street, George Town, Penang. To this day, the High Court sits at the top of Penang's hierarchy of courts.

Hukum Kanun Pahang, also known as Kanun Pahang or Undang-Undang Pahang was the Qanun or legal code of the old Pahang Sultanate. It contains significant provisions that reaffirmed the primacy of Malay adat, while at the same time accommodating and assimilating the Islamic law. The legal code was largely modelled on the Undang-Undang Melaka and Undang-Undang Laut Melaka, and was compiled during the reign of the 12th Sultan of Pahang, Abdul Ghafur Muhiuddin Shah. It is regarded as one of the oldest digest of laws compiled in the Malay world.