The Malacca Sultanate was a Malay sultanate based in the modern-day state of Malacca, Malaysia. Conventional historical thesis marks c. 1400 as the founding year of the sultanate by King of Singapura, Parameswara, also known as Iskandar Shah, although earlier dates for its founding have been proposed. At the height of the sultanate's power in the 15th century, its capital grew into one of the most important transshipment ports of its time, with territory covering much of the Malay Peninsula, the Riau Islands and a significant portion of the northern coast of Sumatra in present-day Indonesia.

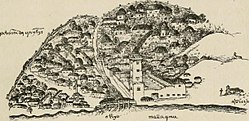

Malacca City is the capital city of the Malaysian state of Malacca, in Melaka Tengah District. It is the oldest Malaysian city on the Straits of Malacca, having become a successful entrepôt in the era of the Malacca Sultanate. The present-day city was founded by Parameswara, a Sumatran prince who escaped to the Malay Peninsula when Srivijaya fell to the Majapahit. Following the establishment of the Malacca Sultanate, the city drew the attention of traders from the Middle East, South Asia, and East Asia, as well as the Portuguese, who intended to dominate the trade route in Asia. After Malacca was conquered by Portugal, the city became an area of conflict when the sultanates of Aceh and Johor attempted to take control from the Portuguese.

The Johor Sultanate was founded by Sultan of Malacca Mahmud Shah's son, Alauddin Riayat Shah II in 1528.

Cornelis Matelief de Jonge was a Dutch admiral who was active in establishing Dutch power in Southeast Asia during the beginning of the 17th century. His fleet was officially on a trading mission, but its true intent was to destroy Portuguese power in the area. The fleet had 1400 men on board, including 600 soldiers. Matelieff did not succeed in this. The Dutch would ultimately gain control of Malacca more than thirty years later, again joining forces with the Sultanate of Johor, and a new ally Aceh, in 1641. He was born and died in Rotterdam.

Tanjungpinang, also colloquially written as Tanjung Pinang, is the capital city of the Indonesian province of Riau Islands. It covers a land area of 144.56 km2, mainly in the southern part of Bintan Island, as well as other smaller islands such as Dompak Island and Penyengat Island. With a population of 227,663 at the 2020 Census, it is the second largest city of the province, after Batam; the official estimate as at mid 2023 was 234,840. Tanjungpinang is a historic city of the Malay culture, having served as the capital of both Johor Sultanate and Riau-Lingga Sultanate.

Hang Nadim was a warrior of the Johor-Riau during the Portuguese occupation of Melaka. Nadim was appointed laksamana (admiral) of Sultan Mahmud Shah's forces that harassed the Portuguese trade colonies from 1511 to 1526. He also appears as a legendary figure in a chapter of the Sejarah Melayu.

Johor Lama is a mukim in Kota Tinggi District, Johor, Malaysia. It is situated on the banks of Johor River. It was once a thriving port and the old capital of the Johor Sultanate.

Laksamana Tun Abdul Jamil Paduka Raja was a Malay warrior of the Johor Sultanate. He played a major role in trying to wrest Malacca from Portuguese control.

The Sultanate of Aceh, officially the Kingdom of Aceh Darussalam, was a sultanate centered in the modern-day Indonesian province of Aceh. It was a major regional power in the 16th and 17th centuries, before experiencing a long period of decline. Its capital was Kutaraja, the present-day Banda Aceh.

Sultan Alauddin Riayat Shah II ibni Almarhum Sultan Mahmud Shah was the first Sultan of Johor and ruled from 1528 to 1564. He founded the Johor Sultanate following the fall of Malacca to the Portuguese in 1511. He was the second son of Mahmud Shah of Malacca. Thus, Johor was a successor state of Malacca and Johor's sultans follow the numbering system of Malacca. Throughout his reign, he faced constant threats from the Portuguese as well as the emerging Aceh Sultanate.

The Battle of Cape Rachado, off Cape Rachado in 1606, was an important naval engagement between the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and Portuguese Navy.

Dutch Malacca (1641–1825) was the longest period that Malacca was under foreign control. The Dutch ruled for almost 183 years with intermittent British occupation during the French Revolutionary and later the Napoleonic Wars (1795–1815). This era saw relative peace with little serious interruption from the Malay sultanates due to the understanding forged between the Dutch and the Sultanate of Johor in 1606. This period also marked the decline of Malacca's importance. The Dutch preferred Batavia as their economic and administrative centre in the region and their hold in Malacca was to prevent the loss of the city to other European powers and, subsequently, the competition that would come with it. Thus, in the 17th century, with Malacca ceasing to be an important port, the Johor Sultanate became the dominant local power in the region due to the opening of its ports and the alliance with the Dutch.

Iskandar Muda was the twelfth Sultan of Acèh Darussalam, under whom the sultanate achieved its greatest territorial extent, holding sway as the strongest power and wealthiest state in the western Indonesian archipelago and the Strait of Malacca.

Muar or Bandar Maharani, is a historical town and the capital of Muar District, Johor, Malaysia. It is one of the most popular tourist attractions in Malaysia to be visited and explored for its food, coffee and historical prewar buildings. It was recently declared as the royal town of Johor by Sultan Ibrahim Sultan Iskandar and is the fourth largest urban area in Johor. It is the main and biggest town of the bigger entity region or area of the same name, Muar which is sub-divided into the Muar district and the new Tangkak district, which was upgraded into a full-fledged district from the Tangkak sub-district earlier. Muar district as the only district covering the whole area formerly borders Malacca in the northern part. Upon the upgrading of Tangkak district, the Muar district now covers only the area south of Sungai Muar, whilst the northern area beyond the river is in within Tangkak district. However, both divided administrative districts are still collectively and fondly called and referred to as the region or area of Muar as a whole by their residents and outsiders. Currently, the new township of Muar is located in the Bakri area.

The Capture of Malacca in 1511 occurred when the governor of Portuguese India Afonso de Albuquerque conquered the city of Malacca in 1511.

Kalinyamat Sultanate or Kalinyamat Kingdom, was a 16th-century Javanese Islamic polity in the northern part of the island of Java, centred in modern-day Jepara, Central Java, Indonesia.

The War of the League of the Indies was a military conflict lasting from December 1570 to 1575, wherein a pan-Asian alliance attempted to overturn the Portuguese presence in the Indian Ocean. The pan-Asian alliance was formed primarily by the Sultanate of Bijapur, the Sultanate of Ahmadnagar, the Kingdom of Calicut, and the Sultanate of Aceh. It is referred to by the Portuguese historian António Pinto Pereira as "the League of Kings of India", "the Confederated Kings", or simply "the League". The alliance undertook a combined assault against some of the primary possessions of the Portuguese State of India: Malacca, Chaul, the Chale fort, and the capital of the maritime empire in Asia, Goa.

The Pahang Sultanate also referred as the Old Pahang Sultanate, as opposed to the modern Pahang Sultanate, was a Malay Muslim state established in the eastern Malay Peninsula in the 15th century. At the height of its influence, the sultanate was an important power in Southeast Asia and controlled the entire Pahang basin, bordering the Pattani Sultanate to the north and the Johor Sultanate to the south. To the west, its jurisdiction extended over parts of modern-day Selangor and Negeri Sembilan.

Malay–Portuguese conflicts were military engagements between the forces of the Portuguese Empire and the various Malay states and dynasties, fought intermittently from 1509 to 1641 in the Malay Peninsula and Strait of Malacca.

Acehnese–Portuguese conflicts were the military engagements between the forces of the Portuguese Empire, established at Malacca in the Malay Peninsula, and the Sultanate of Aceh, fought intermittently from 1519 to 1639 in Sumatra, the Malay Peninsula or the Strait of Malacca. The Portuguese supported, or were supported, by various Malay or Sumatran states who opposed Acehnese expansionism, while the Acehnese received support from the Ottoman Empire and the Dutch East India Company.