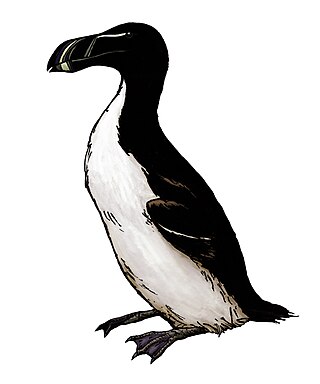

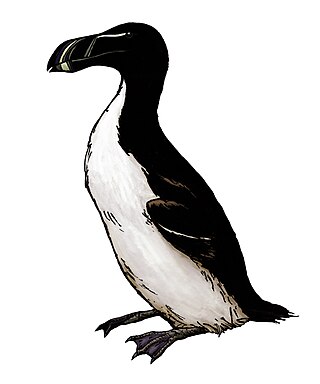

The great auk is a species of flightless alcid that became extinct in the mid-19th century. It was the only modern species in the genus Pinguinus. It is not closely related to the Southern Hemisphere birds now known as penguins, which were discovered later by Europeans and so named by sailors because of their physical resemblance to the great auk, which were called penguins.

Penguins are a group of aquatic flightless birds from the order Sphenisciformes of the family Spheniscidae. They live almost exclusively in the Southern Hemisphere: only one species, the Galápagos penguin, is found north of the Equator. Highly adapted for life in the ocean water, penguins have countershaded dark and white plumage and flippers for swimming. Most penguins feed on krill, fish, squid and other forms of sea life which they catch with their bills and swallow whole while swimming. A penguin has a spiny tongue and powerful jaws to grip slippery prey.

Puffins are any of three species of small alcids (auks) in the bird genus Fratercula. These are pelagic seabirds that feed primarily by diving in the water. They breed in large colonies on coastal cliffs or offshore islands, nesting in crevices among rocks or in burrows in the soil. Two species, the tufted puffin and horned puffin, are found in the North Pacific Ocean, while the Atlantic puffin is found in the North Atlantic Ocean.

An auk or alcid is a bird of the family Alcidae in the order Charadriiformes. The alcid family includes the murres, guillemots, auklets, puffins, and murrelets. The family contains 25 extant or recently extinct species that are divided into 11 genera.

Falcons are birds of prey in the genus Falco, which includes about 40 species. Falcons are widely distributed on all continents of the world except Antarctica, though closely related raptors did occur there in the Eocene.

Guillemot is the common name for several species of seabird in the Alcidae or auk family. In British use, the term comprises two genera: Uria and Cepphus. In North America the Uria species are called murres and only the Cepphus species are called "guillemots". This word of French origin derives from a form of the name William, cf. French: Guillaume.

The Anatidae are the biological family of water birds that includes ducks, geese, and swans. The family has a cosmopolitan distribution, occurring on all the world's continents except Antarctica. These birds are adapted for swimming, floating on the water surface, and in some cases diving in at least shallow water. The family contains around 174 species in 43 genera.

Phalacrocoracidae is a family of approximately 40 species of aquatic birds commonly known as cormorants and shags. Several different classifications of the family have been proposed, but in 2021 the International Ornithologists' Union (IOU) adopted a consensus taxonomy of seven genera. The great cormorant and the common shag are the only two species of the family commonly encountered in Britain and Ireland and "cormorant" and "shag" appellations have been later assigned to different species in the family somewhat haphazardly.

The rhinoceros auklet is a seabird and a close relative of the puffins. It is the only extant species of the genus Cerorhinca. Given its close relationship with the puffins, the common name rhinoceros puffin has been proposed for the species.

Cerorhinca is a genus of auk containing the rhinoceros auklet and several fossil species.

The great albatrosses are seabirds in the genus Diomedea in the albatross family. The genus Diomedea formerly included all albatrosses except the sooty albatrosses, but in 1996 the genus was split, with the mollymawks and the North Pacific albatrosses both being elevated to separate genera.

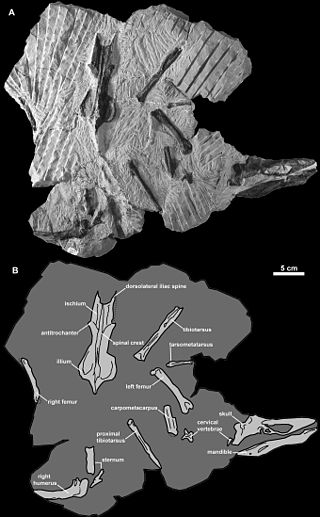

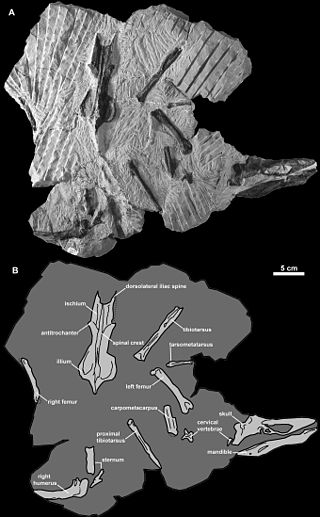

Mancalla is an extinct genus of prehistoric flightless alcids that lived on the Pacific coast of today's California and Mexico during the Late Miocene to Early Pliocene.

Aethia is a genus of four small (85–300g) auklets endemic to the North Pacific Ocean, Bering Sea and Sea of Okhotsk and among some of North America's most abundant seabirds. The relationships between the four true auklets remains unclear. Auklets are threatened by invasive species such as Norway rats because of their high degree of coloniality and crevice-nesting.

The Pelagornithidae, commonly called pelagornithids, pseudodontorns, bony-toothed birds, false-toothed birds or pseudotooth birds, are a prehistoric family of large seabirds. Their fossil remains have been found all over the world in rocks dating between the Early Paleocene and the Pliocene-Pleistocene boundary.

Paleontology or palaeontology is the study of prehistoric life forms on Earth through the examination of plant and animal fossils. This includes the study of body fossils, tracks (ichnites), burrows, cast-off parts, fossilised feces (coprolites), palynomorphs and chemical residues. Because humans have encountered fossils for millennia, paleontology has a long history both before and after becoming formalized as a science. This article records significant discoveries and events related to paleontology that occurred or were published in the year 1976.

Pinguinus alfrednewtoni is an extinct species of auk related to the great auk known from fossils that were discovered in the Pliocene Yorktown Formation of North Carolina. Like the great auk, it was a large flightless diving bird that used its wings to propel itself forward underwater. Only a limited amount of material is known, despite the rich diversity of fossil auks recovered from the Yorktown Formation. Due to this, it has been proposed that it was either a more coastal animal or simply not as common in more southern waters. This later suggestion could be supported by the discovery of relatively young P. alfrednewtoni remains, indicating that they may have overwintered in the region. One early hypothesis proposed that it was a direct ancestor to the great auk, but this idea is no longer supported. Instead, it is thought that it filled the same niche as its eastern relative, which eventually expanded into the western Atlantic after the extinction of P. alfrednewtoni.

Miomancalla is an extinct genus of prehistoric flightless alcids that lived on the Pacific coast of today's California in the Miocene epoch. It contained two species, M. howardi and M. wetmorei.

Pan-Alcidae is a clade of charadriiform birds containing the auks and their extinct relatives. It was named in 2011 by N.A. Smith, who defined it as all descendants of the common ancestor of the group Mancallinae and crown group auks (Alcidae), but some have disputed the use of the Pan- prefix in general for family-group names regulated by the Zoocode.

Dow's puffin is an extinct seabird in the auk family described in 2000 from subfossil remains found in the Channel Islands of California. It was approximately as large as the modern horned puffin and its beak appeared to have been an intermediate between the rhinoceros auklet and the horned puffin. It lived during the Late Pleistocene and Early Pleistocene on the Channel Islands, where it nested alongside the ancient murrelet, Cassin's auklet and Chendytes lawi.

Gavia brodkorbi is an extinct species of loon from the Clarendonian age from United States. The holotype and only known specimen is a complete left ulna that was collected from the Monterey Formation in Laguna Niguel, California by Marion J. Bohreer in 1969. The ulna is shorter but more stouter in comparison to the red-throated loon and pacific loon. The area of attachment of the ligaments is different from the extant species, as it is shorter and less oval. Hildegarde Howard would described the bird in 1978 on a paper discussing the Late Miocene seabird fauna of Orange County named the species after Pierce Brodkorb for his contribution for the field of paleornithology including his review of Pliocene loons.