Myiasis, also known as flystrike or fly strike, is the parasitic infestation of the body of a live animal by fly larvae (maggots) that grow inside the host while feeding on its tissue. Although flies are most commonly attracted to open wounds and urine- or feces-soaked fur, some species can create an infestation even on unbroken skin and have been known to use moist soil and non-myiatic flies as vector agents for their parasitic larvae.

Mulesing is the removal of strips of wool-bearing skin from around the breech (buttocks) of a sheep to prevent the parasitic infection flystrike (myiasis). The wool around the buttocks can retain feces and urine, which attracts flies. The scar tissue that grows over the wound does not grow wool, so is less likely to attract the flies that cause flystrike. Mulesing is a common practice in Australia for this purpose, particularly on highly wrinkled Merino sheep. Mulesing is considered by some to be a skilled surgical task. Mulesing can only affect flystrike on the area cut out and has no effect on flystrike on any other part of the animal's body.

Warble fly is a name given to the genus Hypoderma: large flies which are parasitic on cattle and deer. Other names include "heel flies", "bomb flies" and "gadflies", while their larvae are often called "cattle grubs" or "wolves." Common species of warble fly include Hypoderma bovis and Hypoderma lineatum and Hypoderma tarandi. Larvae of Hypoderma species also have been reported in horses, sheep, goats and humans. They have also been found on smaller mammals such as dogs, cats, squirrels, voles and rabbits.

Sheep dip is a liquid formulation of insecticide and fungicide that shepherds and farmers use to protect their sheep from infestation against external parasites such as itch mite, blow-fly, ticks and lice.

The common green bottle fly is a blowfly found in most areas of the world and is the most well-known of the numerous green bottle fly species. Its body is 10–14 mm (0.39–0.55 in) in length – slightly larger than a house fly – and has brilliant, metallic, blue-green or golden coloration with black markings. It has short, sparse, black bristles (setae) and three cross-grooves on the thorax. The wings are clear with light brown veins, and the legs and antennae are black. The larvae of the fly may be used for maggot therapy, are commonly used in forensic entomology, and can be the cause of myiasis in livestock and pets. The common green bottle fly emerges in the spring for mating.

Hippoboscidae, the louse flies or keds, are obligate parasites of mammals and birds. In this family, the winged species can fly at least reasonably well, though others with vestigial or no wings are flightless and highly apomorphic. As usual in their superfamily Hippoboscoidea, most of the larval development takes place within the mother's body, and pupation occurs almost immediately.

The cat flea is an extremely common parasitic insect whose principal host is the domestic cat, although a high proportion of the fleas found on dogs also belong to this species. This is despite the widespread existence of a separate and well-established "dog" flea, Ctenocephalides canis. Cat fleas originated in Africa but can now be found globally. As humans began domesticating cats, the prevalence of the cat flea increased and it spread throughout the world.

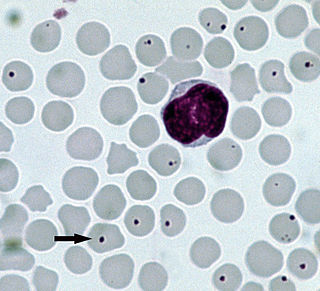

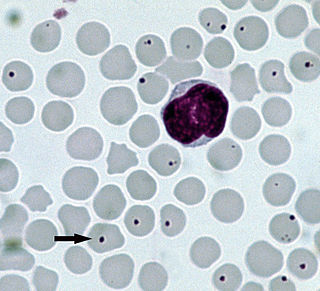

Anaplasmosis is a tick-borne disease affecting ruminants, dogs, and horses, and is caused by Anaplasma bacteria. Anaplasmosis is an infectious but not contagious disease. Anaplasmosis can be transmitted through mechanical and biological vector processes. Anaplasmosis can also be referred to as "yellow bag" or "yellow fever" because the infected animal can develop a jaundiced look. Other signs of infection include weight loss, diarrhea, paleness of the skin, aggressive behavior, and high fever.

The raising of domestic sheep has occurred in nearly every inhabited part of the earth, and the variations in cultures and languages which have kept sheep has produced a vast lexicon of unique terminology used to describe sheep husbandry.

Lipoptena depressa, or the Western American deer ked, is species of fly in the family Hippoboscidae. The flies are blood-feeding ectoparasites of mule deer, Odocoileus hemionus and white-tailed deer, Odocoileus virginianus. They are found in the western United States and Canada.

Lucilia cuprina, formerly named Phaenicia cuprina, the Australian sheep blowfly is a blow fly in the family Calliphoridae. It causes the condition known as "sheep strike"'. The female fly locates a sheep with ideal conditions, such as an open wound or a build-up of faeces or urine in the wool, in which she lays her eggs. The emerging larvae cause large lesions on the sheep, which may prove to be fatal.

There are various disparate groups of wingless insects. Apterygota are a subclass of small, agile insects, distinguished from other insects by their lack of wings in the present and in their evolutionary history. They include Thysanura . Some species lacking wings are members of insect orders that generally do have wings. Some do not grow wings at all, having "lost" the possibility in the remote past. Some have reduced wings that are not useful for flying. Some develop wings but shed them after they are no longer useful. Other groups of insects may have castes with wings and castes without, such as ants. Ants have alate queens and males during the mating season and wingless workers, which allows for smaller workers and more populous colonies than comparable winged wasp species.

Hippobosca longipennis, the dog fly, louse fly, or blind fly, is a blood-feeding parasite mostly infesting carnivores. The species name "longipennis" means "long wings". Its bites can be painful and result in skin irritation, it is an intermediate host for the canine and hyaenid filarial parasite Dipetalonema dracunculoides, "and it may also be a biological or mechanical vector for other pathogens".

Ticks of domestic animals directly cause poor health and loss of production to their hosts. Ticks also transmit numerous kinds of viruses, bacteria, and protozoa between domestic animals. These microbes cause diseases which can be severely debilitating or fatal to domestic animals, and may also affect humans. Ticks are especially important to domestic animals in tropical and subtropical countries, where the warm climate enables many species to flourish. Also, the large populations of wild animals in warm countries provide a reservoir of ticks and infective microbes that spread to domestic animals. Farmers of livestock animals use many methods to control ticks, and related treatments are used to reduce infestation of companion animals.

Mites that infest and parasitize domestic animals cause disease and loss of production. Mites are small invertebrates, most of which are free living but some are parasitic. Mites are similar to ticks and both comprise the order Acari in the phylum Arthropoda. Mites are highly varied and their classification is complex; a simple grouping is used in this introductory article. Vernacular terms to describe diseases caused by mites include scab, mange, and scabies. Mites and ticks have substantially different biology from, and are classed separately from, insects. Mites of domestic animals cause important types of skin disease, and some mites infest other organs. Diagnosis of mite infestations can be difficult because of the small size of most mites, but understanding how mites are adapted to feed within the structure of the skin is useful.

Mites are small crawling animals related to ticks and spiders. Most mites are free-living and harmless. Other mites are parasitic, and those that infest livestock animals cause many diseases that are widespread, reduce production and profit for farmers, and are expensive to control.

Sodalis is a genus of bacteria within the family Pectobacteriaceae. This genus contains several insect endosymbionts and also a free-living group. It is studied due to its potential use in the biological control of the tsetse fly. Sodalis is an important model for evolutionary biologists because of its nascent endosymbiosis with insects.

Many species of flies of the two-winged type, Order Diptera, such as mosquitoes, horse-flies, blow-flies and warble-flies, cause direct parasitic disease to domestic animals, and transmit organisms that cause diseases. These infestations and infections cause distress to companion animals, and in livestock industry the financial costs of these diseases are high. These problems occur wherever domestic animals are reared. This article provides an overview of parasitic flies from a veterinary perspective, with emphasis on the disease-causing relationships between these flies and their host animals. The article is organized following the taxonomic hierarchy of these flies in the phylum Arthropoda, order Insecta. Families and genera of dipteran flies are emphasized rather than many individual species. Disease caused by the feeding activity of the flies is described here under parasitic disease. Disease caused by small pathogenic organisms that pass from the flies to domestic animals is described here under transmitted organisms; prominent examples are provided from the many species.