Ungulates are members of the diverse clade Euungulata, which primarily consists of large mammals with hooves. Once part of the clade "Ungulata" along with the clade Paenungulata, "Ungulata" has since been determined to be a polyphyletic and thereby invalid clade based on molecular data. As a result, true ungulates had since been reclassified to the newer clade Euungulata in 2001 within the clade Laurasiatheria while Paenungulata has been reclassified to a distant clade Afrotheria. Living ungulates are divided into two orders: Perissodactyla including equines, rhinoceroses, and tapirs; and Artiodactyla including cattle, antelope, pigs, giraffes, camels, sheep, deer, and hippopotamuses, among others. Cetaceans such as whales, dolphins, and porpoises are also classified as artiodactyls, although they do not have hooves. Most terrestrial ungulates use the hoofed tips of their toes to support their body weight while standing or moving. Two other orders of ungulates, Notoungulata and Litopterna, both native to South America, became extinct at the end of the Pleistocene, around 12,000 years ago.

Artiodactyls are placental mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla. Typically, they are ungulates which bear weight equally on two of their five toes. The other three toes are either present, absent, vestigial, or pointing posteriorly. By contrast, most perissodactyls bear weight on an odd number of the five toes. Another difference between the two orders is that many artiodactyls digest plant cellulose in one or more stomach chambers rather than in their intestine. Molecular biology, along with new fossil discoveries, has found that cetaceans fall within this taxonomic branch, being most closely related to hippopotamuses. Some modern taxonomists thus apply the name Cetartiodactyla to this group, while others opt to include cetaceans within the existing name of Artiodactyla. Some researchers use "even-toed ungulates" to exclude cetaceans and only include terrestrial artiodactyls, making the term paraphyletic in nature.

Andrewsarchus, meaning "Andrews' ruler", is an extinct genus of artiodactyl that lived during the Middle Eocene in what is now China. The genus was first described by Henry Fairfield Osborn in 1924 with the type species A. mongoliensis based on a largely complete cranium. A second species, A. crassum, was described in 1977 based on teeth. A mandible, formerly described as Paratriisodon, does probably belong to Andrewsarchus as well. The genus has been historically placed in the families Mesonychidae or Arctocyonidae, or was considered to be a close relative of whales. It is now regarded as the sole member of its own family, Andrewsarchidae, and may have been related to entelodonts. Fossils of Andrewsarchus have been recovered from the Middle Eocene Irdin Manha, Lushi, and Dongjun Formations of Inner Mongolia, each dated to the Irdinmanhan Asian land mammal age.

Creodonta is a former order of extinct carnivorous placental mammals that lived from the early Paleocene to the late Miocene epochs in North America, Europe, Asia and Africa. Originally thought to be a single group of animals ancestral to the modern Carnivora, this order is now usually considered a polyphyletic assemblage of two different groups, the oxyaenids and the hyaenodontids, not a natural group. Oxyaenids are first known from the Palaeocene of North America, while hyaenodonts hail from the Palaeocene of Africa.

Entelodontidae is an extinct family of pig-like artiodactyls which inhabited the Northern Hemisphere from the late Eocene to the early Miocene epochs, about 38-19 million years ago. Their large heads, low snouts, narrow gait, and proposed omnivorous diet inspires comparisons to suids and tayassuids (peccaries), and historically they have been considered closely related to these families purely on a morphological basis. However, studies which combine morphological and molecular (genetic) data on artiodactyls instead suggest that entelodonts are cetancodontamorphs, more closely related to hippos and cetaceans through their resemblance to Pakicetus, than to basal pigs like Kubanochoerus and other ungulates.

Pakicetus is an extinct genus of amphibious cetacean of the family Pakicetidae, which was endemic to Indian Subcontinent during the Ypresian period, about 50 million years ago. It was a wolf-like mammal, about 1–2 m long, and lived in and around water where it ate fish and other animals. The name Pakicetus comes from the fact that the first fossils of this extinct amphibious whale were discovered in Pakistan. The vast majority of paleontologists regard it as the most basal whale, representing a transitional stage between land mammals and whales. It belongs to the even-toed ungulates with the closest living non-cetacean relative being the hippopotamus.

Mesonyx is a genus of extinct mesonychid mesonychian mammal. Fossils of the various species are found in Early to Late Eocene-age strata in the United States and Early Eocene-aged strata in China, 51.8—51.7 Ma (AEO).

Ichthyolestes is an extinct genus of archaic cetacean that was endemic to Indo-Pakistan during the Lutetian stage. To date, this monotypic genus is only represented by Ichthyolestes pinfoldi.

Sinonyx is a genus of extinct, superficially wolf-like mesonychid mammals from the late Paleocene of China. It is within the family Mesonychidae, and cladistic analysis of a skull of Sinonyxjiashanensis identifies its closest relative as Ankalagon. S.jiashanensis was discovered in Anhui province, China, in the Tuijinshan formation.

Patriofelis is an extinct genus of carnivorous placental mammals from the extinct subfamily Oxyaeninae within the extinct family Oxyaenidae. It was a large cat-like predator which lived in North America during the Bridgerian NALMA. Fossils have been found in Wyoming, Colorado, and Oregon.

Mesonychidae is an extinct family of small to large-sized omnivorous-carnivorous mammals. They were endemic to North America and Eurasia during the Early Paleocene to the Early Oligocene, and were the earliest group of large carnivorous mammals in Asia. Once considered a sister-taxon to artiodactyls, recent evidence now suggests no close connection to any living mammal. Mesonychid taxonomy has long been disputed and they have captured popular imagination as "wolves on hooves", animals that combine features of both ungulates and carnivores. Skulls and teeth have similar features to early whales, and the family was long thought to be the ancestors of cetaceans. Recent fossil discoveries have overturned this idea; the consensus is that whales are highly derived artiodactyls. Some researchers now consider the family a sister group either to whales or to artiodactyls, close relatives rather than direct ancestors. Other studies define Mesonychia as basal to all ungulates, occupying a position between Perissodactyla and Ferae. In this case, the resemblances to early whales would be due to convergent evolution among ungulate-like herbivores that developed adaptations related to hunting or eating meat.

Dissacus is a genus of extinct carnivorous jackal to coyote-sized mammals within the family Mesonychidae, an early group of hoofed mammals that evolved into hunters and omnivores. Their fossils in Paleocene to Early Eocene aged strata in France, Asia and southwest North America, from 66 to 50.3 mya, existed for approximately 15.7 million years.

Pachyaena was a genus of heavily built, relatively short-legged mesonychids, early Cenozoic mammals that evolved before the origin of either modern hoofed animals or carnivores, and combined characteristics similar to both. The genus likely originated from Asia and spread to Europe, and from there to North America across a land bridge in what is now the North Atlantic ocean. Various described species of Pachyaena ranged in size from a coyote to a bear. However, recent work indicates that Pachyaena is paraphyletic, with P. ossifraga being closer to Synoplotherium, Harpagolestes and Mesonyx than to P. gigantea.

Hapalodectidae is an extinct family of relatively small-bodied mesonychian placental mammals from the Paleocene and Eocene of North America and Asia. Hapalodectids differ from the larger and better-known mesonychids by having teeth specialized for cutting, while the teeth of other mesonychids, such as Mesonyx or Sinonyx, are more specialized for crushing bones. Hapalodectids were once considered a subfamily of the Mesonychidae, but the discovery of a skull of Hapalodectes hetangensis showed additional differences justifying placement in a distinct family. In particular, H. hetangensis has a postorbital bar closing the back of the orbit, a feature lacking in mesonychids. The skeleton of hapalodectids is poorly known, and of the postcranial elements, only the humerus has been described. The morphology of this bone indicates less specialization for terrestrial locomotion than in mesonychids.

Triisodontidae is an extinct, probably paraphyletic, or possibly invalid family of mesonychian placental mammals. Most triisodontid genera lived during the Paleocene in North America, but the genus Andrewsarchus is known from the middle Eocene of Asia. Triisodontids were the first relatively large predatory mammals to appear in North America following the extinction of the non-bird dinosaurs. They differ from other mesonychian families in having less highly modified teeth.

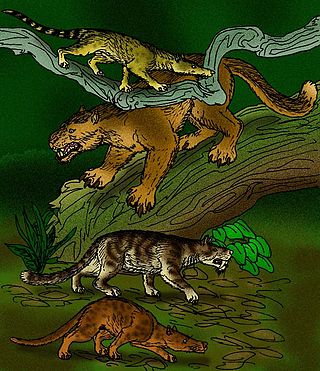

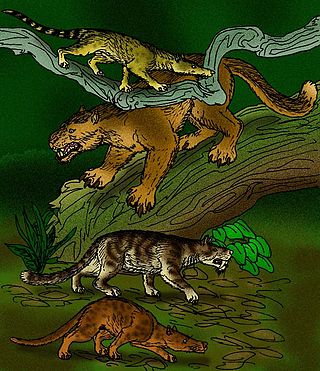

Arctocyonidae is as an extinct family of unspecialized, primitive mammals with more than 20 genera. Animals assigned to this family were most abundant during the Paleocene, but extant from the late Cretaceous to the early Eocene . Like most early mammals, their actual relationships are very difficult to resolve. No Paleocene fossil has been unambiguously assigned to any living order of placental mammals, and many genera resemble each other: generalized robust, not very agile animals with long tails and all-purpose chewing teeth, living in warm closed-canopy forests with many niches left vacant by the K-T extinction.

Ankalagon saurognathus is an extinct carnivorous mammal of the family Mesonychidae, endemic to North America during the Paleocene epoch, existing for approximately 3.1 million years.

Triisodon is a genus of extinct mesonychian mammal that existed during the Early Paleocene of New Mexico, North America, from about 63.5-62.0 Ma. The genus was named by Edward Drinker Cope in 1881 as a member of the Acreodi, a now invalid taxon that encompassed creodonts, mesonychians and certain arctocyonians. Cope described the type specimen of T. quivirensis as "about the size of a wolf." A smaller species, T. crassicuspis, has also been identified from the same region. Since material from this genus is incomplete, the exact size of adults and whether they showed sexual dimorphism or regional variations in size is unknown.

The Willwood Formation is a sedimentary sequence deposited during the late Paleocene to early Eocene, or Clarkforkian, Wasatchian and Bridgerian in the NALMA classification.

Hyaenodonta is an extinct order of hypercarnivorous placental mammals of clade Pan-Carnivora from mirorder Ferae. Hyaenodonts were important mammalian predators that arose during the early Paleocene in Europe and persisted well into the late Miocene.