Names in historical sequence

Lygos

According to Pliny the Elder Byzantium was first known as Lygos. [1] The origin and meaning of the name are unknown. Zsolt suggested it was etymologically identitical to the Greek name for the Ligures and derived from the Anatolian ethnonym Ligyes, [2] a tribe that was part of Xerxes' army [3] and appeared to have been neighbors to the Paphlagonians. [4] Janis believed it may have been the name of a Thracian settlement situated on the site of the later city near the point of the peninsula (Sarayburnu). [5]

Byzantium

Byzantion (Ancient Greek : Βυζάντιον, romanized: Byzántion, Latin : Byzantium) was founded by Greek colonists from Megara in 667 BC. The name is believed to be of Thracian or Illyrian origin and thus to predate the Greek settlement. [5] It may be derived from a Thracian or Illyrian personal name, Byzas. [6] : 352ff Ancient Greek legend refers to a legendary king of that name as the leader of the Megarean colonists and eponymous founder of the city.

Byzántios, plural. Byzántioi (Ancient Greek : Βυζάντιος, Βυζάντιοι, Latin : Byzantius) referred to Byzantion's inhabitants and Byzántios (Ancient Greek : Βυζάντιος, Latin : Byzantius) was an adjective, also used as an ethnonym for the people of the city and as a family name. [7] In the Middle Ages, Byzántion was also a synecdoche for the eastern Roman Empire. (An ellipsis of Medieval Greek : Βυζάντιον κράτος, romanized: Byzántion krátos). [7] Byzantinós (Medieval Greek : Βυζαντινός, Latin : Byzantinus) denoted an inhabitant of the empire. [7] The Anglicization of Latin Byzantinus yielded "Byzantine", with 15th and 16th century forms including Byzantin, Bizantin(e), Bezantin(e), and Bysantin as well as Byzantian and Bizantian. [8] [9]

The name Byzantius and Byzantinus were applied from the 9th century to gold Byzantine coinage, reflected in the French besant (d'or), Italian bisante, and English besant, byzant, or bezant . [7] The English usage, derived from Old French besan (pl. besanz), and relating to the coin, dates from the 12th century. [10]

Later, the name Byzantium became common in the West to refer to the Eastern Roman Empire, whose capital was Constantinople. As a term for the east Roman state as a whole, Byzantium was introduced by the historian Hieronymus Wolf only in 1555, a century after the empire, whose inhabitants called it the Roman Empire (Medieval Greek : Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, romanized: Basileia tōn Rhōmaiōn, lit. 'kingdom of the Romans'), had ceased to exist. [11]

Augusta Antonina

The city was called Augusta Antonina (Greek : Αυγούστα Αντωνινή) for a brief period in the 3rd century AD. The Roman Emperor Septimius Severus (193–211) conferred the name in honor of his son Antoninus, the later Emperor Caracalla. [12]

New Rome

Before the Roman emperor Constantine the Great made the city the new eastern capital of the Roman Empire on May 11, 330, he undertook a major construction project, essentially rebuilding the city on a monumental scale, partly modeled after Rome. Names of this period included ἡ Νέα, δευτέρα Ῥώμη "the New, second Rome", [13] [14] Alma Roma Ἄλμα Ῥώμα, Βυζαντιάς Ῥώμη, ἑῴα Ῥώμη "Eastern Rome", Roma Constantinopolitana. [6] : 354

The Third Canon of the First Council of Constantinople (381) refers to the city as New Rome. [15]

The term "New Rome" lent itself to East-West polemics, especially in the context of the Great Schism, when it was used by Greek writers to stress the rivalry with (the original) Rome. New Rome is also still part of the official title of the Patriarch of Constantinople. [16]

Constantinople

Kōnstantinoúpolis (Κωνσταντινούπολις), Constantinopolis in Latin and Constantinople in English, was the name by which the city became more widely known, in honor of Constantine the Great who established it as his capital. It is first attested in official use under Emperor Theodosius II (408–450). [12] Stephanus of Byzantium mention both the terms Konstantinoupolis (Κωνσταντινούπολις) [17] and Kostantinoupolis (Κωσταντινούπολις). [18] Constantinopolis remained the principal official name of the city throughout the Byzantine period, and the most common name used for it in the West until the early 20th century.

This name was also used (including its Kostantiniyye variant) by the Ottoman Empire to describe the entire urban area of the city until the advent of the Republic of Turkey—the core Walled City was always Istambul for the Ottomans. [19] According to Eldem Edhem, who wrote an encyclopedia entry on Istanbul for Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire, "many" Turkish members of the public as well as Turkish historians often perceive the use of Constantinople for the Ottoman city, despite being historically accurate, as being "politically incorrect". [20]

Other Byzantine names

Besides Constantinople, the Byzantines referred to the city with a large range of honorary appellations, such as the "Queen of Cities" (Βασιλὶς τῶν πόλεων), also as an adjective, Βασιλεύουσα, the 'Reigning City'. In popular speech, the most common way of referring to it came to be simply the City (Greek: hē Polis /iˈpo.lis/, ἡ Πόλις, Modern Greek: i Poli, η Πόλη /i ˈpoli/ ). This usage, still current today in colloquial Greek and Armenian (Պոլիս, pronounced "Polis" or "Bolis" in the Western Armenian dialect prevalent in the city), also became the source of the later Turkish name, Istanbul (see below).

Kostantiniyye

Kostantiniyye (Arabic: القسطنطينية, translit. al-Qusṭanṭīniyya, Persian: قسطنطنیه, translit. Qosṭanṭanīye, Ottoman Turkish: قسطنطينيه, translit. Ḳosṭanṭīnīye) [21] is the name by which the city came to be known in the Islamic world. It is an Arabic calque of Constantinople. After the Ottoman conquest of 1453, it was used as the most formal official name in Ottoman Turkish, [22] and remained in use throughout most of the time up to the fall of the Empire in 1922. However, during some periods Ottoman authorities favoured other names (see below).

Istanbul

The modern Turkish name İstanbul (pronounced [isˈtanbuɫ] ) (Ottoman Turkish : استانبول) is attested (in a range of variants) since the 10th century, at first in Armenian and Arabic (without the initial İ-) and then in Ottoman sources. Some sources have speculated that it comes from the Medieval Greek phrase "εἰς τὴν πόλιν", meaning "to the city", reinterpreted as a single word, but a 2015 review of the literature found a more likely explanation to be that: "The form of the etymon is the colloquial Middle Greek phrase στην Πόλι(ν), not the puristic literary ancestor of this. The meaning of the etymon is probably ‘in Constantinople’, possibly ‘to Constantinople’ and just possibly ‘into Constantinople’". [23] [a]

The incorporation of parts of articles and other particles into Greek place names was common even before the Ottoman period: Navarino for earlier Avarino, [24] Satines for Athines, etc. [25] Similar examples of modern Turkish place names derived from Greek in this fashion are İzmit, earlier İznikmit, from Greek Nicomedia, İznik from Greek Nicaea ([iz nikea]), Samsun (s'Amison from "se" and "Amisos"), and İstanköy for the Greek island Kos (from is tin Ko). The occurrence of the initial i- in these names, including Istanbul's, is largely secondary epenthesis to break up syllabic consonant clusters, prohibited by the phonotactic structure of Turkish, as seen in Turkish istasyon from French station or ızgara from the Greek schára. [23]

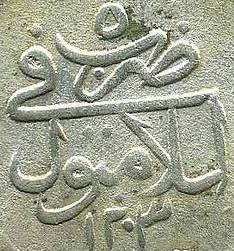

İstanbul originally was not used for the entire city, instead the name referred to the core of Istanbul—the walled city. [20] İstanbul was the common name for the city in normal speech in Turkish even before the conquest of 1453,[ citation needed ] but in official use by the Ottoman authorities other names, such as Kostantiniyye, were preferred in certain contexts. Thus, Kostantiniyye was used on coinage up to the late 17th and then again in the 19th century. The Ottoman chancery and courts used Kostantiniyye as part of intricate formulae in expressing the place of origin of formal documents, such as be-Makam-ı Darü's-Saltanat-ı Kostantiniyyetü'l-Mahrusâtü'l-Mahmiyye. [26] In 19th century Turkish book-printing it was also used in the impressum of books, in contrast to the foreign use of Constantinople. At the same time, however, İstanbul too was part of the official language, for instance in the titles of the highest Ottoman military commander (İstanbul ağası) and the highest civil magistrate (İstanbul efendisi) of the city, [27] [ page needed ] and the Ottoman Turkish version of the Ottoman constitution of 1876 states that "The capital city of the Ottoman State is İstanbul". [28] İstanbul and several other variant forms of the same name were also widely used in Ottoman literature and poetry. [12]

Names other than استانبول (İstanbul) had become obsolete in the Turkish language after the establishment of the Republic of Turkey. [20] However, at that point Constantinople was still used when writing the city's name in Latin script. In 1928, the Turkish alphabet was changed from the Arabic to the Latin script. Beginning in 1930, Turkey officially requested that other countries use Turkish names for Turkish cities, instead of other transliterations to Latin script that had been used in the Ottoman times. [29]

T. R. Ybarra of The New York Times wrote in 1929 that "'Istambul' (our usual form for the word is 'Stamboul') has always been the Turkish name for the whole of Constantinople". [30] The Observer wrote that "To the Turks themselves it never was Constantinople, but Istanbul." [31] In 1929 Lloyd's agents were informed that telegrams now must be addressed to "Istanbul" or "Stamboul", but The Times stated that mail could still be delivered to "Constantinople". [32] However The New York Times stated that year that mail to "Constantinople" may no longer be delivered. [33] In 1929, Turkish government advocated for the use of Istanbul in English instead of Constantinople. [34] The U.S. State Department began using "Istanbul" in May 1930. [35]

In English, the name is usually written "Istanbul". In modern Turkish, the name is written "İstanbul" (dotted i/İ and dotless ı/I being two distinct letters in the Turkish alphabet).

Stamboul

Stamboul or Stambul is a variant form of İstanbul. Like Istanbul itself, forms without the initial i- are attested from early on in the Middle Ages, first in Arabic sources of the 10th century [36] and Armenian ones of the 12th. Some early sources also attest to an even shorter form Bulin, based on the Greek word Poli(n) alone without the preceding article. [37] (This latter form lives on in modern Armenian.) The word-initial i- arose in the Turkish name as an epenthetic vowel to break up the St- consonant cluster, prohibited in Turkish phonotactics.

Stamboul was used in Western languages to refer to the central city, as Istanbul did in Turkish, until the time it was replaced by the official new usage of the Turkish form in the 1930s for the entire city. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Western European and American sources often used Constantinople to refer to the metropolis as a whole, but Stamboul to refer to the central parts located on the historic peninsula, i.e. Byzantine-era Constantinople inside the walls. [20]

Islambol

The name Islambol (اسلامبولlit. 'full of Islam') appeared after the Ottoman conquest of 1453 to express the city's new role as the capital of the Islamic Ottoman Empire. It was first attested shortly after the conquest, and its invention was ascribed by some contemporary writers to sultan Mehmed II himself. [12] Some Ottoman sources of the 17th century, most notably Evliya Çelebi, describe it as the common Turkish name of the time. Between the late 17th and late 18th centuries, it was also in official use. The first use of the word "Islambol" on coinage was in 1730 during the reign of sultan Mahmud I. [38] The term Kostantiniyye still appeared, however, into the 20th century.

Other Ottoman names

Ottomans and foreign contemporaries, especially in diplomatic correspondence, referred to the Ottoman imperial government with particular honorifics. Among them are the following: [39]

- Bāb-i ʿĀlī (باب عالی, "The Sublime Porte"); a metonym referring to the gate of Topkapı Palace [39]

- Der-i Devlet (در دولت "Abode of the State") [39]

- Der-i Saʿādet (در سعادت "Abode of Felicity" or "Abode of Eudaimonia") [39]

- Āsitāne (آستانه "Threshold"), referring to the imperial court, [39] a Persian-origin word spelled in English as Asitane [40] or Asitana [41] [42]

- Pāy-taḫt or sometimes Pāyitaḫt (پای تخت, "The Seat/Base of the Throne")

The "Gate of Felicity", the "Sublime Gate", and the "Sublime Porte" were literally places within the Ottoman sultans' Topkapı Palace, and were used metonymically to refer to the authorities located there, and hence for the central Ottoman imperial administration. Modern historians also refer to government by these terms, similar to the popular usage of Whitehall in Britain. The Sublime Gate is not inside Topkapı palace; the administration building whose gate is named Bâb-ı Âlî is between Agia Sofia and Beyazit mosque, a huge building. [43] [ better source needed ]