Emilio Aguinaldo y Famy was a Filipino revolutionary, statesman, and military leader who is the youngest president of the Philippines (1899–1901) and became the first president of the Philippines and of an Asian constitutional republic. He led the Philippine forces first against Spain in the Philippine Revolution (1896–1898), then in the Spanish–American War (1898), and finally against the United States during the Philippine–American War (1899–1901). Though he was not recognized as president outside of the revolutionary Philippines, he is regarded in the Philippines as having been the country's first president during the period of the First Philippine Republic.

Gregorio Hilario del Pilar y Sempio was a Filipino general of the Philippine Revolutionary Army during the Philippine–American War.

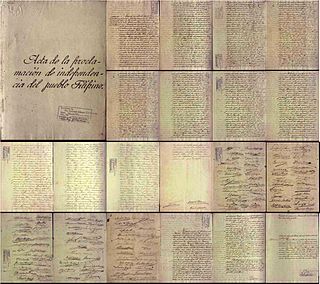

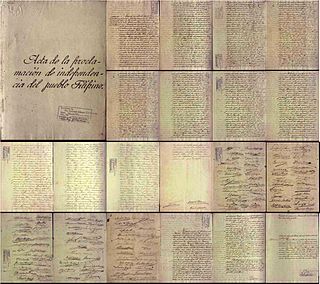

The Philippine Declaration of Independence was proclaimed by Filipino revolutionary forces general Emilio Aguinaldo on June 12, 1898, in Cavite el Viejo, Philippines. It asserted the sovereignty and independence of the Philippine islands from the 300 years of colonial rule from Spain.

Antonio Narciso Luna de San Pedro y Novicio Ancheta was a Filipino army general and a pharmacist who fought in the Philippine–American War before his assassination on June 5, 1899, at the age of 32.

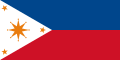

The Philippine Republic, now officially remembered as the First Philippine Republic and also referred to by historians as the Malolos Republic, was established in Malolos, Bulacan during the Philippine Revolution against the Spanish Empire (1896–1898) and the Spanish–American War between Spain and the United States (1898) through the promulgation of the Malolos Constitution on January 23, 1899, succeeding the Revolutionary Government of the Philippines. It was formally established with Emilio Aguinaldo as president. It was unrecognized outside of the Philippines but remained active until April 19, 1901. Following the American victory at the Battle of Manila Bay, Aguinaldo returned to the Philippines, issued the Philippine Declaration of Independence on June 12, 1898, and proclaimed successive revolutionary Philippine governments on June 18 and 23 of that year.

José Torres Bugallón y Gonzales was a Filipino military officer who fought and served the Spanish Government during the Philippine Revolution against the revolutionaries and joins the Philippine Revolutionary Army during the Philippine–American War. He is known as the "Hero of the Battle of La Loma", where he was fatally wounded that led to his death.

The Political Constitution of 1899, informally known as the Malolos Constitution, was the constitution of the First Philippine Republic. It was written by Felipe Calderón y Roca and Felipe Buencamino as an alternative to a pair of proposals to the Malolos Congress by Apolinario Mabini and Pedro Paterno. After a lengthy debate in the latter part of 1898, it was promulgated on January 21, 1899.

Rayadillo is a blue-and-white striped cotton or flannel material that was used to make the military uniforms worn by Spanish colonial soldiers from the later 19th century until the early 20th century. It was commonly worn by soldiers posted in overseas Spanish tropical colonies, Spanish Morocco and Spanish Guinea, before being adopted as a summer uniform by units stationed in Spain itself.

The battle of Caloocan was one of the opening engagements of the Philippine–American War, and was fought between an American force under the command of Arthur MacArthur Jr. and Filipino defenders led by Antonio Luna in February 1899. American troops launched a successful attack on the Filipino-held settlement of Caloocan on February 10, which was part of an offensive planned by MacArthur Jr. Occurring a few days after an American victory near Manila on February 4–5, the engagement once again demonstrated the military superiority that American forces held over the Philippine Revolutionary Army. However, it was not the decisive strike that MacArthur had hoped for, and the war continued for another three years.

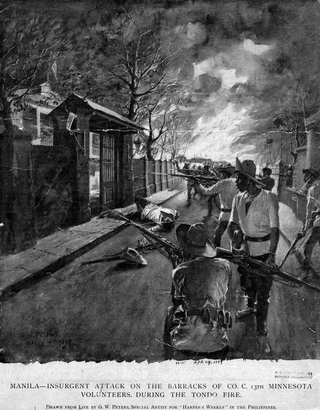

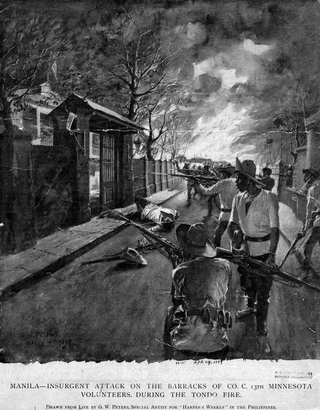

Fighting erupted between forces of the United States and those of the Philippine Republic on February 4, 1899, in what became known as the 1899 Battle of Manila. On June 2, 1899, the First Philippine Republic officially declared war against the United States. The war officially ended on July 2, 1902, with a victory for the United States. However, some Philippine groups—led by veterans of the Katipunan, a Philippine revolutionary society—continued to battle the American forces for several more years. Among those leaders was General Macario Sakay, a veteran Katipunan member who assumed the presidency of the proclaimed Tagalog Republic, formed in 1902 after the capture of President Emilio Aguinaldo. Other groups, including the Moro, Bicol and Pulahan peoples, continued hostilities in remote areas and islands, until their final defeat at the Battle of Bud Bagsak on June 15, 1913.

The Battle of Marilao River was fought on March 27, 1899, in Marilao, Bulacan, Philippines, during the Philippine–American War. It was one of the most celebrated river crossings of the whole war, wherein American forces crossed the Marilao River, which was 80 yards (73 m) wide and too deep to ford, while under Filipino fire from the opposite bank.

The following lists events that happened during 1899 in the Philippine Republic.

Pedro Tongio Liongson was a member of the Malolos Congress which wrote the constitution of the First Philippine Republic in 1899 and served as First Director of Military Justice in the Republic's army during the Philippine–American War of 1899–1901. A trained lawyer and judge, Col. Liongson figured in and left his mark on a number of historic events in the Philippines.

The Second Battle of Caloocan, alternately called the Second Battle of Manila, was fought from February 22 to 24, 1899, in Caloocan during the Philippine–American War. The battle featured a Filipino counterattack aimed at gaining Manila from the Americans. This counterattack failed to regain Manila mainly because of lack of coordination among Filipino units and lack of artillery support.

The Battle of Alapan was fought on May 28, 1898, and was the first military victory of the Filipino Revolutionaries led by Emilio Aguinaldo after his return to the Philippines from Hong Kong. After the American naval victory in the Battle of Manila Bay, Aguinaldo returned from exile in Hong Kong, reconstituted the Philippine Revolutionary Army, and fought against the Spanish troops in a garrison in Alapan, Imus, Cavite. The battle lasted for five hours, from 10:00 A.M. to 3:00 P.M.

The history of the Philippine Army began in during pre-colonial era as different tribes established their own citizen force to defend the Balangays from intruders. Army was organized forces through the years who fought Spanish oppression and even other invaders such as Dutch and British who attempted to conquer the Philippines in early centuries.

FranciscoRomán y Velasquez was a Filipino soldier who became a revolutionary during Philippine Revolution and Philippine–American War. Roman had the rank of a colonel in the Philippine Revolutionary Army, and served as the close aide of General Antonio Luna. When Luna was assassinated in Cabanatuan, Nueva Ecija, Román attempted to save him but he was also shot to death by Emilio Aguinaldo's presidential guards.

Salvador Estrella was a Filipino general who fought in the Philippine Revolution and the Philippine–American War. For his courage in battle, he earned the moniker "red blooded."

The Federal State of the Visayas was a revolutionary state in the Philippine archipelago during the revolutionary period. It was a proposed administrative unit of a Philippines under a federal form of government.

Felipe Buencamino y Siojo was an infamous Filipino turncoat, lawyer, diplomat, and politician. He fought alongside the Spaniards in the Philippine Revolution but later switched sides and joined Emilio Aguinaldo's revolutionary cabinet. He was a member of the Malolos Congress and co-authored the Malolos Constitution. He was also appointed as Secretary of Foreign Relations in the cabinet of Aguinaldo. After he left the revolutionary government, he co-founded the Federalista Party and became a founding member of the Philippine Independent Church.